Student loan forgiveness may be dead. Here’s what’s going on

- Share via

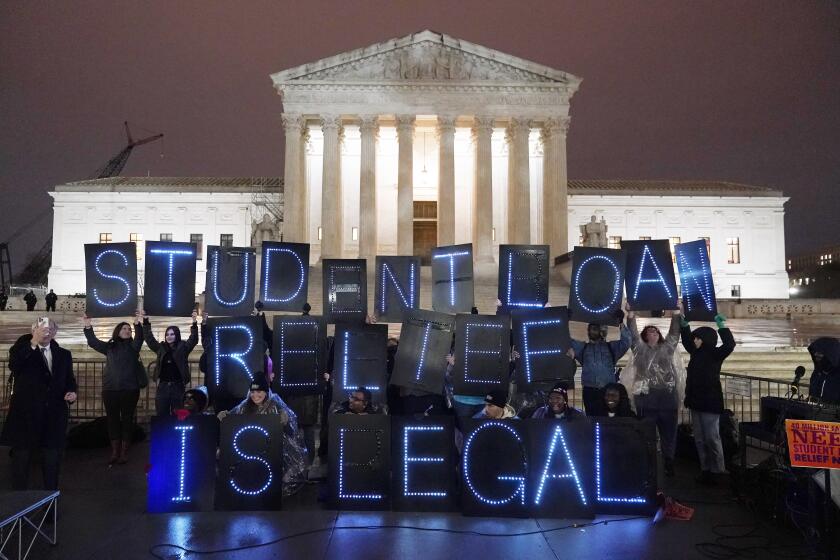

The Biden administration has stopped accepting applications for the student debt relief it announced in August, casting doubt on a program that was intended to help 40 million borrowers.

Two federal courts have issued rulings that barred the program from moving forward — one temporarily, the other permanently. The Biden administration has asked the Supreme Court to throw out those rulings.

In the meantime, the Education Department has extended the pause on federal student loan payments and interest until the legal battle ends or late August 2023, whichever is earlier. Payments and interest had been set to resume in January, after the loan forgiveness program was supposed to go into effect.

The Education Department stopped accepting applications for the one-time debt relief program in response to a ruling on Nov. 10 from U.S. District Judge Mark T. Pittman in Texas, who held that the department didn’t have the legal authority to offer loan forgiveness on that scale.

On Nov. 14, the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals extended the temporary injunction it had imposed on the program while it considers a lawsuit brought by six Republican-controlled states. That lawsuit had been rejected by a lower court judge, prompting the states’ appeal.

Here’s a brief explanation of where things stand and what issues are involved in the lawsuits brought against the debt relief program.

The ruling was in Texas. Will it affect Californians?

Yes. Pittman “vacated” the entire debt relief program, saying the department usurped Congress’ legislative power in violation of the Constitution.

Unless the administration persuades a higher court to overturn Pittman’s ruling, the program is dead.

The moratorium was slated to expire Jan. 1, a date Biden set before his plan stalled in the face of legal challenges from conservative opponents.

I’ve already applied. Will I still get my loans forgiven?

That depends on the outcome of the appeal. White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said Thursday that 26 million borrowers had already applied and 16 million had been approved for loan forgiveness. She added: “The Department will hold onto their information so it can quickly process their relief once we prevail in court.”

What if I haven’t applied yet? Should I still do so?

The department was no longer accepting applications in light of Pittman’s ruling. If its appeal succeeds, it could resume taking applications.

Borrowers who have already reported their annual income from 2020 or 2021 do not need to apply to qualify for the relief, if the program is restored. That’s typically the case for borrowers enrolled in an income-driven repayment plan.

A U.S. judge in Texas has blocked President Biden’s plan to provide millions of borrowers with up to $20,000 apiece in federal student loan forgiveness.

Didn’t the Supreme Court rule in favor of the loan forgiveness program?

Justice Amy Coney Barrett rejected appeals by two of the groups challenging the debt relief, but those orders came in the context of different cases.

Multiple lawsuits have been filed against the loan forgiveness plan, either by conservative interest groups or by Republican state officials. While two of them were dismissed because the plaintiffs couldn’t show that they were injured by the program, two others have gained at least some traction.

The federal government plans to forgive up to $20,000 in student loan debt for millions of Americans. Here’s everything you need to know.

What is the legal argument against the program?

The lawsuits all made the same basic claim: that the Education Department exceeded its legal authority when it offered blanket debt relief to borrowers with federal student loans.

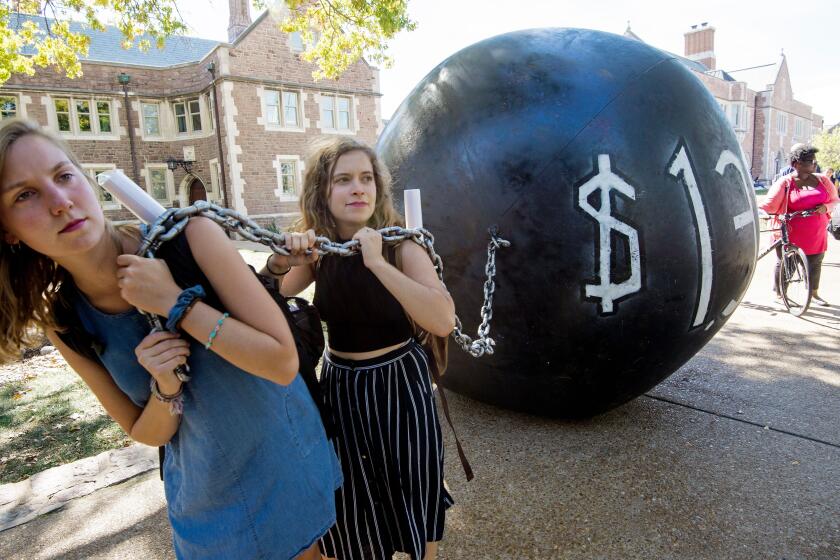

The number of borrowers and the amount of dollars involved are vast. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the program would cost taxpayers an estimated $400 billion.

The Justice Department argues, however, that the 2003 HEROES Act gave the Education Department all the authority it needs. The act gives the department the power to “waive or modify” any requirement for student loans, including those written into federal statutes.

Congress passed the HEROES Act to protect borrowers who were military reservists and National Guard members deployed to combat in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Its powers, however, can be used during a “national emergency” as well as wartime. And the national emergency that President Trump declared at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic has yet to be lifted officially, even though President Biden said (after the loan forgiveness program was announced) that the pandemic was over.

Why are there different rulings if the central legal argument is the same?

Because the threshold issue in each lawsuit is whether the plaintiffs have “standing” to sue — in other words, whether they suffered the sort of harm as individuals that entitles them to seek redress through the courts.

In one case that was dismissed, the only injury alleged by the plaintiffs was the potential cost of the program to all taxpayers. In another, the plaintiffs could avoid the harm (an increase in their state taxes) by turning down the forgiveness the department offered.

In the case brought by six Republican-controlled states, U.S. District Judge Henry E. Autrey in Missouri ruled that the alleged injury — a loss of income from student loan servicing agencies or investments — was either speculative or independent from state finances. The 8th Circuit disagreed, saying Monday that the state of Missouri did have standing to sue. Its order bars the Education Department from granting any debt relief while it weighs the merits of the states’ claims.

The case in Texas had two plaintiffs: Myra Brown, whose loans are privately held and therefore not eligible for the relief program, and Alexander Taylor, who was eligible for up to $10,000 in forgiveness, not $20,000, because he had not received a Pell Grant. Pittman ruled that they could sue because they had not been given the chance to advocate for a forgiveness program that would give them more relief.

Just say no to anyone offering to help you obtain the $10,000 to $20,000 in student loan debt forgiveness. You don’t need them.

What are the critiques of Pittman’s ruling?

Some legal experts said Friday that Pittman made several key mistakes when deciding the two borrowers had standing.

“The standing part is all wrong and inconsistent with everything that’s ever been said about standing,” said George Washington University law professor Richard J. Pierce Jr., an expert in administrative law. Nobody can claim standing to sue by arguing that they should have been a beneficiary of an agency’s action, therefore they were harmed because they weren’t helped, he said.

Scott Anderson, a fellow in Governance Studies at the Brookings Institution, said it’s not that unusual for people to sue because they weren’t allowed to make their case for more aid. But that argument only applies “where there was supposed to be [public] notice and comment” prior to the agency acting, he said.

Pittman’s analysis, Anderson added, “does seem quite generous to the plaintiffs in assessing both their procedural harm and concrete injury.”

As for whether the HEROES Act authorizes the debt relief program, Pittman grounds his ruling in part on the Supreme Court’s decision in West Virginia vs. the Environmental Protection Agency, a case challenging the EPA’s authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. A divided court in June strengthened its “major questions doctrine,” limiting the power of administrative agencies to take actions that have sweeping consequences without specific authority from Congress.

Pierce said that Pittman may have a point there, if the case can overcome its standing issues. But he added that numerous judges, typically Trump appointees like Pittman, “are jumping on the major questions doctrine bandwagon and applying it in case after case” to block agency actions they don’t like.

“And the Supreme Court is going to have to do something to cabin that,” he said, “because it just can’t be used as broadly as some judges are using it today.”

Critiques of Pittman’s ruling aside, the administration doesn’t have an easy path ahead. The appeals court with jurisdiction over the Texas case, the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, is considered to be conservative, so it may be receptive to the arguments advanced by the conservative legal group that brought the lawsuit, the Job Creators Network Foundation. (Ditto for the U.S. Supreme Court.)

Advocates are scrambling to get the word out to public service workers that they could be eligible for a federal program that could wipe out or reduce student loan debt.

Why didn’t congressional Democrats include debt relief in the Inflation Reduction Act?

Because they didn’t have the votes to pass it. Even though Senate rules allowed Democrats to push through the bill on a simple majority vote, it was clear that not all 50 Democrats supported a sweeping debt relief proposal as part of that climate, energy and healthcare bill.

For example, Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-W.Va.) criticized the administration’s debt relief program in September, saying borrowers should have to “earn” loan forgiveness.

About The Times Utility Journalism Team

This article is from The Times’ Utility Journalism Team. Our mission is to be essential to the lives of Southern Californians by publishing information that solves problems, answers questions and helps with decision making. We serve audiences in and around Los Angeles — including current Times subscribers and diverse communities that haven’t historically had their needs met by our coverage.

How can we be useful to you and your community? Email utility (at) latimes.com or one of our journalists: Jon Healey, Ada Tseng, Jessica Roy and Karen Garcia.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.