In red California, election deniers rant about fraud and promise they won’t go away

- Share via

REDDING — A cold rain poured outside as Patty Plumb stood before the Shasta County Board of Supervisors on election day and — with a warm smile and a chipper voice — warned that the local voting system is rigged.

Plumb had conducted a “citizen’s audit” of the local voting rolls a few months ago, knocking on doors in search of fraud.

Dead people had cast ballots, she insisted, along with people who didn’t live in the county. Then there were the electronic voting machines, which Plumb claimed are all connected to the internet and easily hacked by nefarious people.

“The machines need to be turned off, unplugged, melted down and turned into prison bars,” Plumb, 61, said in an interview.

The midterm elections came to this bitterly divided country with a storm of conspiracy theories, bolstered by former President Trump and fanned by allies who support his lie that the 2020 election was stolen from him.

In this mostly rural Northern California county — where Trump beat President Biden by 33 percentage points — local election officials and poll workers have felt threatened and under siege. The split is not so much red versus blue but traditional conservative versus far right.

Republicans who backed Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election lose key races for positions in which they would have overseen elections. But in some areas, they’re poised to win.

“We’re tired. Down-to-the bones tired,” said Cathy Darling Allen, the Shasta County clerk and registrar of voters, who has been harassed and vilified by election deniers.

And so, it was considered a relief — a victory, to some — that election night here came and went peacefully, without violence or intimidation.

But the conspiracy theories about the validity of voting, and the targeting of the elections office, won’t stop any time soon, according to both Allen and local election deniers themselves.

During the June primary election, someone hung a trail camera — the kind hunters use to track wildlife — in the alley behind the county registrar’s office to monitor elections staff.

Private poll watchers trailed volunteers who were driving ballots from polling locations to the county registrar’s office in Redding, in some cases following them from neighboring towns.

As votes were being tallied, Allen heard people outside the elections office tracking her movements, ticking off what times she and another employee had come and gone. Some told her they slept outside all night to prevent anyone from tampering with ballots.

Ultraconservative candidates sought to take control of government in this Northern California county, but mainstream Republicans mostly prevailed.

For the first time in her 18 years as county registrar, she grew so worried about her staff that she asked Redding police to escort them to their vehicles.

Then in September, Allen said, she learned of a group knocking on doors, pretending to be election workers and saying they were part of a “voter task force.”

They wore reflective vests. And instead of conducting door-to-door canvassing, they were driving into neighborhoods, targeting specific homes and aggressively questioning voters about their registration, Allen said.

Worried they would create “a chilling effect on people even being registered to vote,” Allen sounded the alarm, putting out news releases that warned of voter intimidation. She alerted authorities.

Former President Trump’s dominant role may have cost the Republican Party in the midterm elections, but he’s unlikely to walk away quietly.

Members of the group, including Plumb, called her a liar. They swore they were just sweet older people out to save democracy.

“We’re pretty scary, huh?” said Plumb’s cowboy hat-clad husband, Ronald, 71, outside the supervisors’ meeting, where he insisted that all elections in this country have been corrupt for probably the last 50 years.

Shasta County, home to 180,000 people, has become a lightning rod for political discourse in recent years.

Mainstream Republicans have long held power in local government but have been roiled in recent years by a populist flank to their right, including members of a local militia, secessionists who wish to carve their own state of Jefferson out of California’s conservative northern counties, and residents furious about coronavirus mandates.

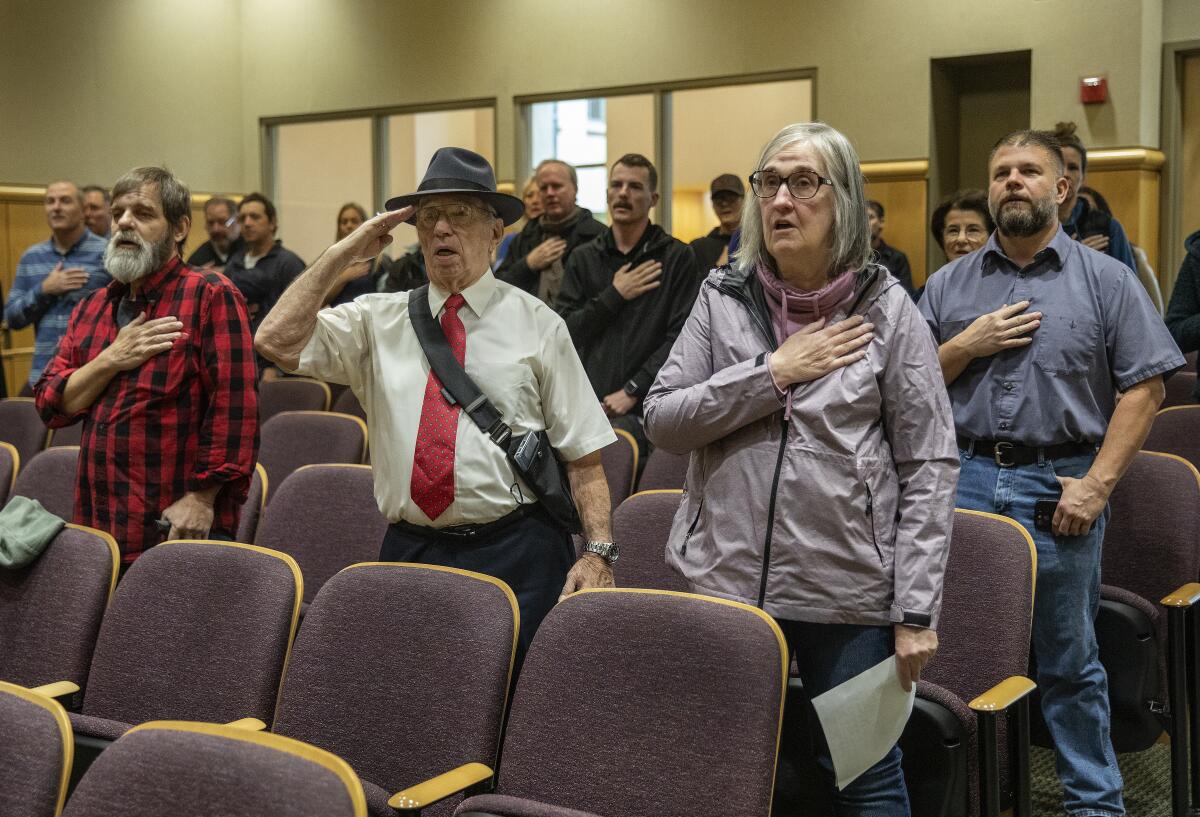

On Jan. 5, 2021 — the day before the deadly siege at the U.S. Capitol — the rage hit a tipping point when residents poured into the Board of Supervisors’ chambers for what was supposed to be a virtual meeting.

Tensions are rising in Shasta County, where a far-right group wants to recall supervisors, has threatened foes and bragged about ties to law enforcement.

“Flee now while you can,” Timothy Fairfield of Shingletown warned the supervisors. “Because the days of your tyranny are drawing to a close, and the legitimacy of this government is waning.

“When the ballot box is gone, there is only the cartridge box. You have made bullets expensive. But luckily for you, ropes are reusable.”

This February, ultraconservatives stunned the state’s political establishment by recalling Supervisor Leonard Moty, a Republican former police chief, in large part because he enforced state-mandated coronavirus restrictions.

Bankrolled by Reverge Anselmo, a former Hollywood filmmaker turned vintner who abandoned the county after a bitter land use dispute, they then backed a slate of six men for the June election.

Their candidates were mostly rejected. As votes were being counted, a group that included militia members and election deniers showed up at the old Montgomery Ward building in downtown Redding that houses the elections office.

A red wave fails to materialize as the abortion issue boosts Democrats and Trump’s intervention costs Republicans in several races.

Allen — a registered Democrat who was on the ballot herself — said she was peppered with the same questions about the voting machines and ballot security for hours.

“They didn’t believe that anyone that works here could be trusted with a ballot without one of them present,” Allen said of the poll watchers. “For some of these folks, this is like a new religion.”

At public meetings, residents regularly quote MyPillow chief executive and pro-Trump conspiracy theorist Mike Lindell, ask to crack open and inspect the county’s Dominion voting machines, and call Allen a criminal.

This week, Allen said she was worried about her staff.

Asked whether her family worries for her, Allen said her husband, “an Idaho farm boy,” recently got a concealed weapons permit.

At the county supervisors meeting the morning of the election, speaker after speaker came to the microphone during public comments to say the vote was going to be rigged.

Susanne Baremore, 53, of Redding made a counterargument. She said that extremism was “infiltrating local politics” and that she believed Shasta County elections are “free and fair and accurate.”

As she walked back to her seat, Supervisor Patrick Jones — who has questioned Dominion voting machines and called for paper recounts of recent elections — mispronounced her name.

When she corrected him, he retorted: “Most of what you say, I highly disagree with.”

In her public comments, Patty Plumb said she had submitted the results of her group’s citizens’ audit to the Shasta County sheriff — proof, she said, of rampant voter fraud.

A Shasta County supervisors’ meeting was faced with verbal threats to government officials and talk of civil war. “You have made bullets expensive. But luckily for you, ropes are reusable,” one person threatened.

With a smile, she warned that Shasta County Sheriff Michael Johnson would be criminally complicit in election malfeasance if he does not act.

“This gives our sheriff the opportunity to do the right thing,” Plumb said. “And if people don’t do the right thing? Um, unfortunately, the sheriff could be in prison. ... We don’t want that to happen to Michael. We like him.”

Plumb told The Times that she and her husband traveled to Missouri in August to attend Lindell’s “Moment of Truth” conference, where he spread unfounded claims about voter fraud.

Lindell exhorted his followers to obtain “cast vote records” — enormous spreadsheets generated by voting machines — to hunt for fraud. That’s exactly what Plumb and the Shasta County citizen auditors did.

Despite the bluster that morning, election day proceeded smoothly. Some voters, both conservative and liberal, said they still believe in the system.

After casting his ballot at Redding City Hall, Charlie Tuggle laughed when asked whether he believed his vote would be accurately counted. Yes, he said, unequivocally.

“I’m a constitutionalist conservative libertarian,” said Tuggle, 41, a welder fabricator. “I don’t wear a tinfoil hat.”

He voted for Republican state Sen. Brian Dahle for governor over incumbent Gavin Newsom and is tired of the state’s liberal politics and high taxes — but the conspiracy theories aren’t helpful, he said.

Former U.S. Marine Reverge Anselmo had a beef with Shasta County land use officials. So he used his riches to remake the county board. He’s not done yet.

After casting her ballot with her husband and 18-year-old son, who voted for the first time, Lorrie Forseth called Shasta County’s misinformation-laden politics embarrassing.

“It doesn’t represent who we really are,” said Forseth, a 56-year-old Democrat who was born and raised here. “When we feel concerned to say where we’re from because of the politics, it’s disheartening.”

At the county registrar’s office that night, elections staff prepared for a melee.

With a special permit from the city, they blocked off an alleyway behind the building where volunteers dropped off ballots from precincts — the same place where someone hung the trail camera and accosted poll workers in June.

A few sheriff’s deputies were stationed around the building.

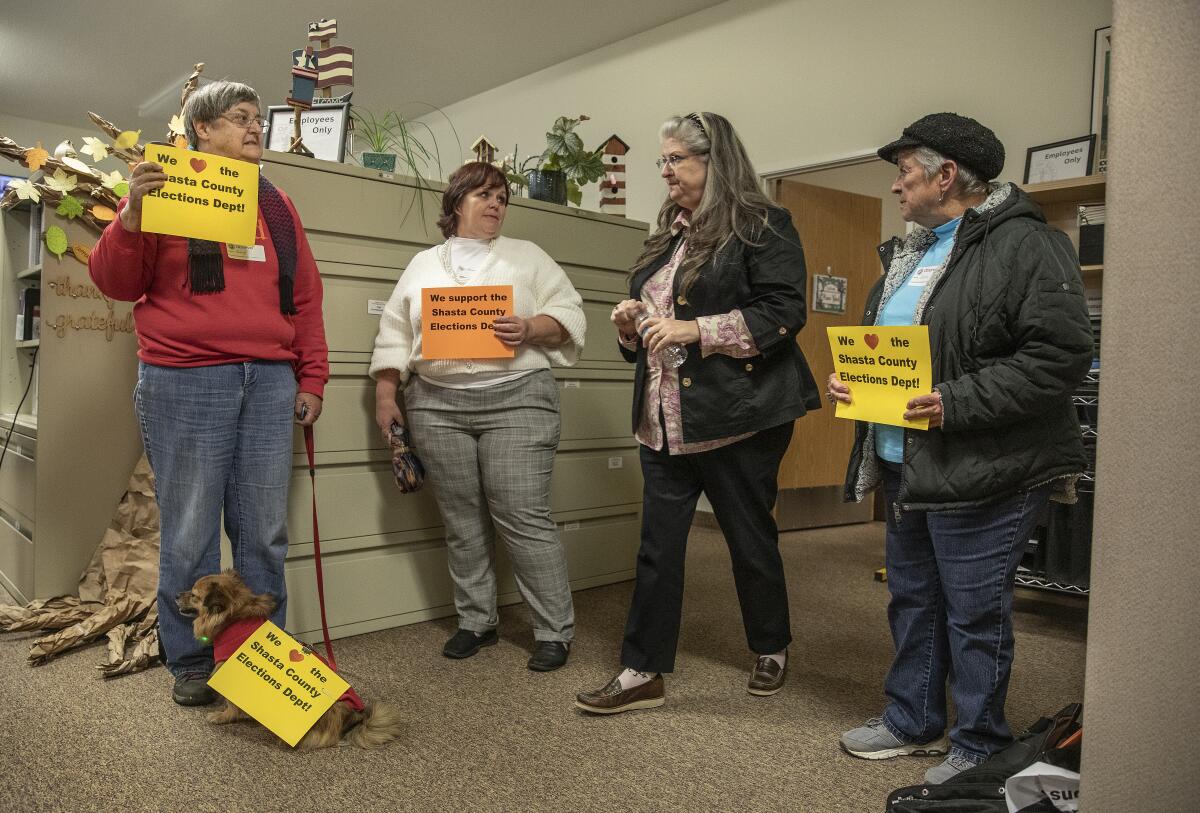

Five minutes before polls closed, Cheryl McKinley, the 70-year-old chair of the Democratic Women’s Club of Shasta County, came bearing pizza and signs that read: “We [Heart] the Shasta County Elections Dept!”

She affixed a sign to Gryffin, her 6-year-old Tibetan spaniel, and stood outside the vote-tabulating room in a sweatshirt that read: “READ!”

“In June, there was haranguing of Cathy Darling Allen, and we’re hoping to stand here and make sure that doesn’t happen again,” she said.

And — it didn’t.

When Allen yelled, “The polls are closed!” at exactly 8 p.m., volunteers cheered.

Outside, where it was 41 degrees, Richard Gallardo, who was losing his bid to join the county Board of Education, demanded to be let in the closed alleyway to keep tabs on election workers.

In 2020, Gallardo announced at a county meeting that he was placing all of the supervisors under citizen’s arrest. Sheriff’s deputies escorted him out, and no officials were jailed.

On social media this week, Gallardo implored poll watchers to take pictures of records printed by voting machines to look for false information.

As he tried to push past the barricades in the alley, someone called the cops.

The big group of poll watchers never materialized. Gallardo stood in the rain with a friend, muttering.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.