Massive learning setbacks show COVID’s sweeping toll on kids across the country, data show

- Share via

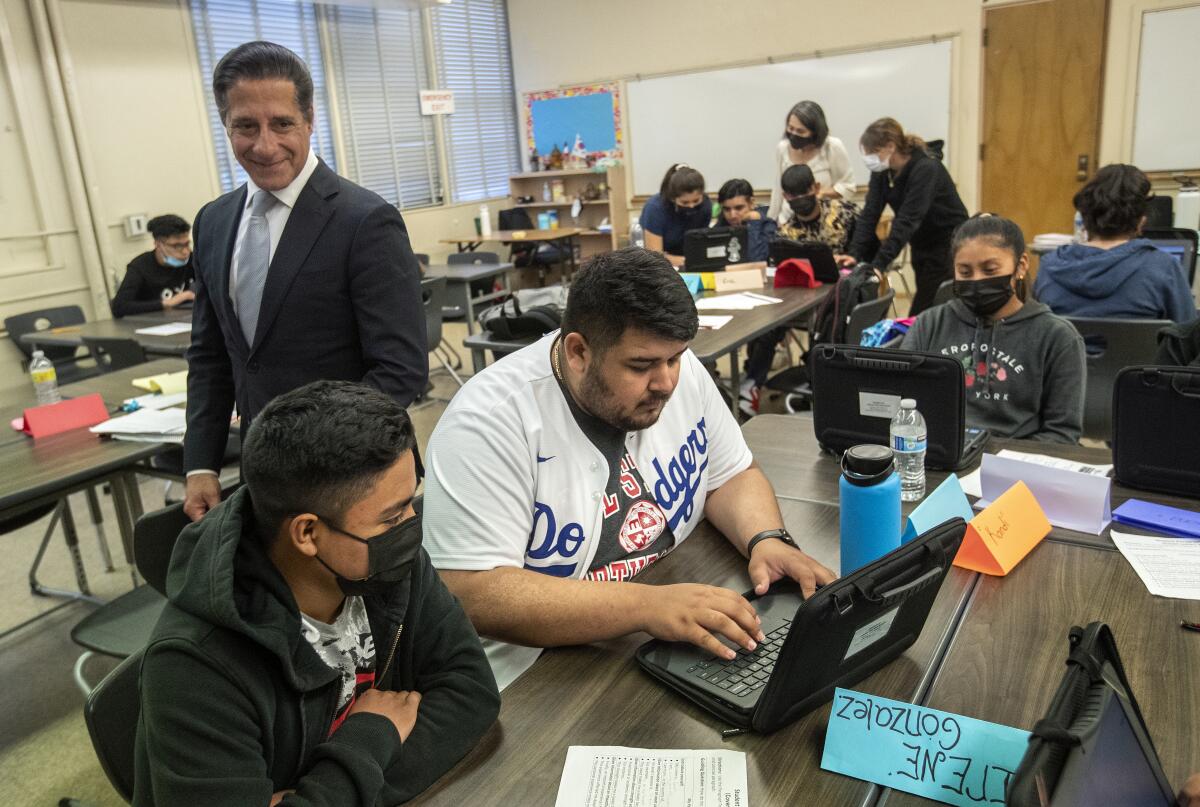

The COVID-19 pandemic devastated poor children’s well-being, not just by closing their schools, but also by taking away their parents’ jobs, sickening their families and teachers, and adding chaos and fear to their daily lives.

The scale of the disruption to American education is evident in a district-by-district analysis of test scores. The data provide the most comprehensive look yet at how much schoolchildren have fallen behind academically.

The analysis found the average student lost more than half a school year of learning in math and nearly a quarter of a school year in reading — with some district averages slipping by more than double those amounts, or worse.

While the picture was not as bleak in California, here, too, there was delayed or lost learning. In Los Angeles Unified — the nation’s second largest school district — the loss in math translates to about half a year in learning. In reading, however, test scores held fairly steady — working out to a loss of a little more than a week in learning.

The release of the data was the latest in a busy week for test scores, with results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress as well as from California’s own state testing program. The national assessment allows for a rough state-by-state comparison using a relatively small sample of fourth and eighth grade students. The state tests offer a more comprehensive look within California — because the state attempts to test all students in Grades 3 through 8 as well as in Grade 11.

The latest data — assembled by researchers at Stanford and Harvard — attempt to build a unified picture by combining these state and national results. Researchers also wanted to understand what led to the varying results — but were left with incomplete answers.

Broadly speaking, students learned less the longer they remained in remote learning before returning to in-person instruction, but the correlation was inconsistent. Students lost significant ground even where they returned quickly to campus, especially in math scores in low-income communities.

“When you have a massive crisis, the worst effects end up being felt by the people with the least resources,” said Stanford education professor Sean Reardon, who compiled and analyzed the data along with Harvard economist Thomas Kane.

Some educators have objected to the very idea of measuring learning loss after a crisis that has killed more than 1 million Americans. Reading and math scores don’t tell the entire story about what’s happening with a child, but they’re one of the only aspects of children’s development reliably measured nationwide.

“Test scores aren’t the only thing, or the most important thing,” Reardon said. “But they serve as an indicator for how kids are doing.”

Declines in math and reading scores on the ‘nation’s report card’ were widespread, with about one in four eighth-graders achieving proficiency in math.

And children aren’t doing well, especially those who were at highest risk before the pandemic. The data show many children need significant intervention, the researchers said, adding that school systems around the country are not doing enough — and the funding for the task is likely to be inadequate in most places.

Kane compared the current effort to the space program to reach the moon.

“What many districts are doing now is effectively shooting bottle rockets at the moon, launching small-scale interventions, which are directionally correct, but won’t add up to anything sufficient to help students catch up,” Kane said.

“Think about it,” he said. “The average kid missed half a year of learning in math. And we’re not going to make up for half a year of learning with a few extra days of instruction or by providing tutors to 5-or-10% of kids.”

Together, Reardon and Kane created a map showing how many years of learning the average student in each district has lost compared to what students in that district were learning in 2019. Their project, the Education Recovery Scorecard, incorporates the national assessment results, froma test known as the “nation’s report card” with scores on different state-level tests from 29 states and Washington, D.C.

The amount of learning that students lost — or gained, in rare cases — over the last three years varied widely. Poverty and time spent in remote learning affected learning loss, and learning losses were greater in districts that remained online longer, according to Kane and Reardon’s analysis. But neither was a perfect predictor of declines in reading and math.

Campuses remained closed in California longer than elsewhere, but student achievement was not worse in that state than in Florida or Texas, which reopened campuses quickly.

Within California, the picture varied greatly for reasons that are hard to explain or simply not known.

In ranking the rise or drop in scores for reading, L.A. Unified was 142nd among 557 school systems with data that could be analyzed. That means 141 school systems were ahead of L.A. Unified when judged by a comparison of scores before and after the pandemic. A few school systems actually saw their reading scores improve when compared with testing prior to the pandemic.

Among those same 557 districts, L.A. Unified ranked 138th in poverty level.

In math, none of the 557 California districts had higher scores than prior to the pandemic.

The alarming dip in math proficiency and smaller declines in English in the last two pandemic-disrupted school years hit students who were already behind.

L.A. Unified was tied with 10 other school systems, including Riverside Unified, for 247th in the state rankings, according to the analysis. L.A. Unified scores were below the state average prior to the pandemic.

In some districts, students fell behind more than two years of math learning, according to the data. In Hopewell, Va., a school system of 4,000 students, mostly from low-income families, 60% are Black. The scores showed an average loss of 2.29 years of school.

“This is not anywhere near what we wanted to see,” Deputy Superintendent Jay McClain said.

The district began offering in-person learning in March 2021, but three-quarters of students remained home. “There was so much fear of the effects of COVID,” he said. “Families here were just hunkered down.”

When schools resumed in the fall, the virus swept through Hopewell, and half of all students stayed home either sick or in quarantine, McClain said. A full 40% of students were chronically absent, meaning they missed 18 days or more.

Chronic absenteeism for similar reasons also was a major problem in Los Angeles and other local school systems.

The pandemic brought other challenges unrelated to remote learning.

Nearly half of L.A. students were chronically absent last year. Educators say they must bring children back to class.

In Rochester, N.H., students lost nearly two years in reading even though schools offered in-person learning most of the 2020-21 school year. It was the largest literacy decline among all the districts in the analysis.

The 4,000-student district, where most are white and nearly half live in poverty, had to close schools in November 2020 when too few teachers could report for work, Superintendent Kyle Repucci said. Students studied online until March 2021, and when schools reopened, many chose to stay with remote learning, Repucci said.

“Students here were exposed to things they should never have been exposed to until much later,” Repucci said. “Death. Severe illness. Working to feed their families.”

It’s hard to know what explains the vastly different outcomes in some states. In California, where students on average stayed steady or only marginally declined in reading scores, it could suggest that educators there were better at teaching over Zoom or the state made effective investments in technology, Reardon said.

But the differences could also be explained by what happened outside of school. “I think a lot more of the variation has to do with things that were outside of a school’s control,” Reardon said.

Now, the onus is on America’s adults to work toward students’ recovery, the researchers said. For the federal government and individual states, advocates hope the recent releases of test data could inspire more urgency to direct funding to the students who suffered the largest setbacks, whether it’s academic or other support.

School systems are still spending the nearly $190 billion in federal relief money allocated for recovery, a sum experts have said fails to address the extent of learning loss in schools. Nearly 70% of students live in districts where federal relief money is likely inadequate to address the magnitude of their learning loss, according to Kane and Reardon’s analysis.

The implications are alarming: Lower test scores are predictors of lower wages, plus higher rates of incarceration and teen pregnancy, Kane said.

Kane said it’s important for parents to understand the gravity of the situation and most do not. He cited data indicating that more than 90% of parents believe their child to be at grade level.

“I’m not blaming parents,” Kane said. “What they see is their kid coming home from school happy or happy to go to school.”

But parents need to grasp the true picture, he said.

“Parent perception is an important constraint on district action,” Kane said. “No district leader is going to be able to propose potentially unpopular things — like using school vacation weeks for additional instruction or extending the school year, extending the school day — if parents think kids are fine.”

“It’s actually less about dollars and more about a common sense of urgency,” he said.

Toness and Lurye are staff writer for the Associated Press. Blume is a Times staff writer.

The Associated Press education team receives support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.