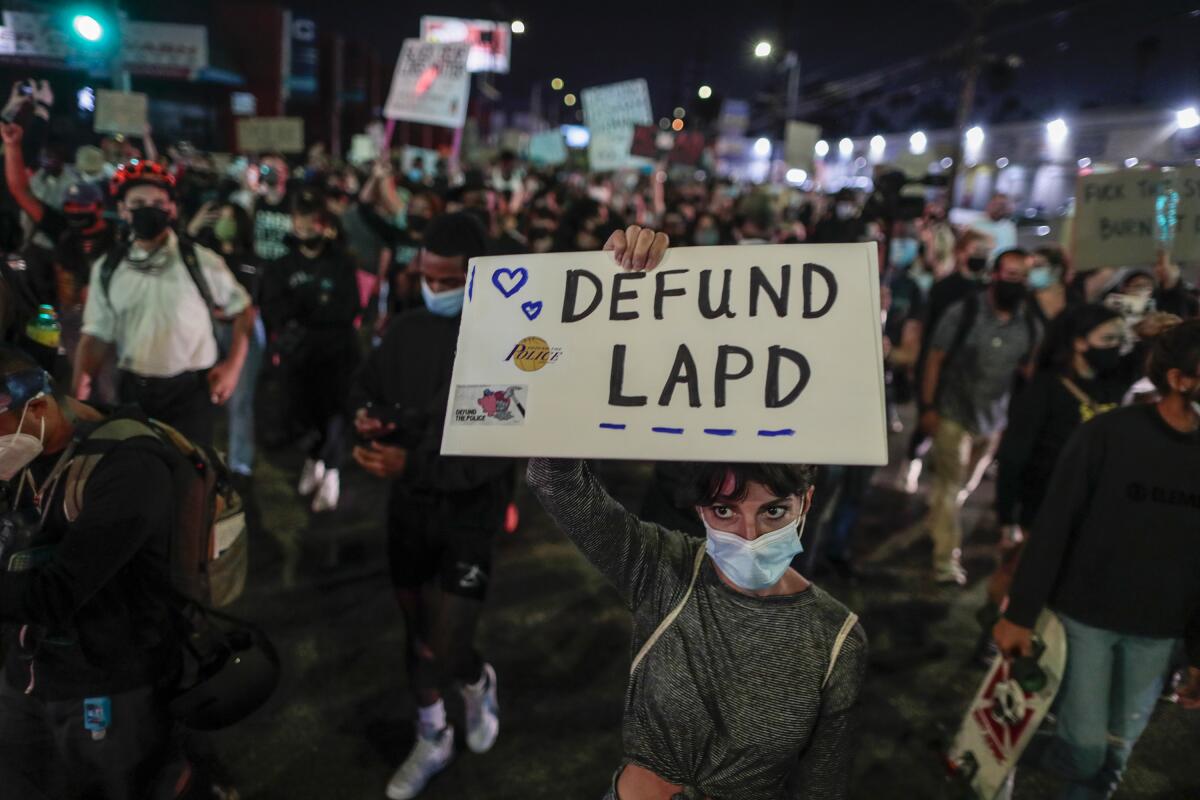

They called for defunding the LAPD. Now they’re looking to defeat City Council members

- Share via

Not long after the death of George Floyd in 2020, labor organizer Hugo Soto-Martinez protested at Echo Park Lake, where he and hundreds of others demanded cuts to the Los Angeles Police Department.

“We’re not going to stop until we defund the police, get rid of [Dist. Atty.] Jackie Lacey and transform this society,” he wrote on Twitter.

Weeks later, college administrator Dulce Vasquez posted her response to the City Council’s decision to cut hundreds of LAPD officers. “Protesting works,” she wrote, with the hashtag #DefundPolice.

Community activist Eunisses Hernandez was issuing her own calls for change, saying funding should be moved out of law enforcement and into housing, child care and other social services.

“When we say abolish the police,” she wrote last year, “we mean replace it with this.”

Now, all three are running for Los Angeles City Council in the June 7 election, looking to unseat a trio of incumbents who have served on the body for nearly a decade.

All three challengers are mounting credible campaigns, hoping to replicate the 2020 success of Nithya Raman, who became the first council candidate to unseat an incumbent in 17 years. Two years after the city erupted in protest over police killings, those candidates — and several others — will test the public’s appetite for reining in law enforcement spending.

Hernandez is running against Councilman Gil Cedillo on the Eastside. Vasquez is challenging Councilman Curren Price in South Los Angeles. Soto-Martinez is looking to unseat Councilman Mitch O’Farrell in Hollywood.

O’Farrell, Price and Cedillo say they are already working to transform policing by adding body cameras, bringing on mental health specialists and making other changes. Each of them voted last year to study the idea of moving traffic enforcement away from armed officers, although progress on that has been slow.

The three incumbents backed a $150-million reduction to Mayor Eric Garcetti’s police budget in 2020, only to favor an increase a year later. And they have resisted demands from activists for a “People’s Budget” that would eviscerate law enforcement spending.

“The people in this city do not want to abolish the police. They do not want to defund the police,” Cedillo said in an interview. “The increase in crime — it’s very visible. People see it.”

The race for the three council seats comes at a turning point for the LAPD. Last year, the number of homicides in the city reached its highest point since 2006, in large part due to increased gun violence.

The LAPD now has 9,371 officers, down from about 10,000 in 2020. Meanwhile, fatal shootings by police have spiked, sparking demands for a more humane response to people facing addiction and mental health challenges.

Nowhere is the array of views on public safety as vast as in O’Farrell’s district, which takes in such areas as Silver Lake and Atwater Village.

Get the lowdown on L.A. politics

Sign up for our L.A. City Hall newsletter to get weekly insights, scoops and analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The field to unseat him includes Steve Johnson, a sergeant in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department who wants to add about 1,500 police officers. Johnson has criticized O’Farrell for scaling back police spending in 2020, saying the move contributed to the decline in LAPD staffing.

“It never should have been cut in the first place,” he said.

At the other end of the spectrum is Albert Corado, whose sister was shot to death by police in 2018 during a standoff in Silver Lake. Corado, a self-described police abolitionist, has the endorsement of Melina Abdullah, co-founder of Black Lives Matter-Los Angeles, and has spoken in vivid terms about shutting down the LAPD.

“I hope to one day make s’mores while the LAPD headquarters in downtown burns to the ground,” Corado wrote last year. “Who’s bringing the marshmallows?”

On Twitter, Corado has called police cadets “future murderers” and suggested more than once that LAPD officers “eat” their own guns. He has argued in favor of eliminating the entire $3-billion police budget, with the proceeds going to social workers, mental health and antipoverty programs.

“If you do all that,” he said during a recent candidate forum, “crime is going to drop so drastically that the rest of it is just going to be up to us, to figure out how to keep each other safe.”

The race also features Soto-Martinez, a hotel union organizer who secured the support of the L.A. chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America and Ground Game L.A. — groups that have called for abolishing the police.

Soto-Martinez said the city needs fewer officers and more mental health counselors, trained mediators and addiction specialists.

“We know that police officers do not prevent crime,” he said at one forum. “They show up after it happens.”

Still, Soto-Martinez’s public safety message has varied, depending on the audience.

In a questionnaire circulated by L.A.’s Democratic Socialists, he was asked if he is a police abolitionist and checked the box indicating “yes.” On that form, he described abolition as “an eventual goal,” saying he favors “caring for our communities, instead of violently oppressing our neighbors.”

But Soto-Martinez offered a more muted response during a candidate forum hosted by groups in the Windsor Square area. At that event, the candidates were asked to raise their hands to indicate whether they think defunding the police is a good idea. The only one who did was Corado.

Soto-Martinez later said it was “ridiculous” for the issue to be reduced to a “hand raise.” He described abolition as a goal that would be reached only after the city has taken major steps to combat economic and racial injustice.

Corado, Soto-Martinez and a third candidate, former council aide Kate Pynoos, have signed a “no new cops” pledge circulated by the People’s Budget Coalition, which is led by Black Lives Matter-L.A. Signers of that document must commit to voting against any plan for hiring additional police above attrition.

Pynoos, who worked for Councilman Mike Bonin, said she has a record of advising her former boss on proposals to cut the number of police officers and take traffic enforcement away from the LAPD. She said she is not an abolitionist but would seek to boost funding for affordable housing, mental health and unarmed crisis responders.

“Throwing more money at LAPD is not going to make us safer,” she said.

Soto-Martinez, for his part, said he would replace every officer who leaves the department with twice as many mental health professionals or other unarmed workers — an approach that would shrink the LAPD even more.

“If it came to a specific vote on whether to hire armed officers to replace the resigned/retired ones, Hugo would vote against that,” said campaign spokesman Josh Androsky, and “in favor of investing more into unarmed responders and social programs that actually prevent crime.”

O’Farrell said he thinks the LAPD needs more officers but did not specify how many. The city, he said, needs to get a handle on violent crime, which is up about 7% from last year.

“You don’t reduce that by defunding the police,” the councilman said in an interview.

With such a large field of candidates, the race will likely produce a Nov. 8 runoff between the top two. That’s not expected in South L.A.’s 9th District, where Price, a two-term incumbent, is facing a vigorous challenge from Vasquez.

Vasquez, who works for Arizona State University, said she supports defunding the police. But her public safety strategy is more moderate than the ones being pushed by some of O’Farrell’s opponents.

Vasquez, who signed the “no new cops” pledge, said she would support hiring enough officers to keep the department at its authorized strength of 9,706, the number backed by the council last year.

At the same time, Vasquez said, she would work to ensure that police no longer handle traffic enforcement, mental health calls, clerical duties or complaint calls about homeless encampments.

“Ultimately, that will decrease our police budget,” she said.

Price has already played a role in shifting funds away from the LAPD. Last year, he succeeded in moving about $90 million out of the department and into job programs, anti-gang initiatives, a guaranteed income program and other community services.

Despite those efforts, Price said he does not view himself as a “defund” candidate. He said he would be open to a “reasonable request” from the department for additional funds.

“Our Black and brown communities are concerned that if police are defunded, we would bear the brunt of the decrease in public safety services,” he said.

On the issue of the LAPD, a much sharper contrast can be found between the two candidates running to represent the heavily Latino 1st District, which stretches from Highland Park south to Pico-Union.

Cedillo, like Price and O’Farrell, voted repeatedly over the past decade to increase the police budget, signing off on several raises for officers. He has described L.A. as “the most under-policed big city in America” and has concluded that voters are worried about their personal safety.

“You cannot be dismissive of the crime that’s taking place,” said Cedillo, who lives downtown. “If people go to Target or Rite Aid, they don’t want to be there when someone is smashing and grabbing.”

Hernandez, on the other hand, is a police abolitionist who has focused on the closure of jails and prisons. As the head of the criminal justice reform group La Defensa, she campaigned successfully in 2020 for passage of Measure J, a ballot item aimed at moving hundreds of millions of dollars away from county law enforcement and into social services.

“I’ve seen how incarcerating folks has just not kept us safe, and so I do believe we need to divert people out of our carceral system,” she said. “It’s about care, and getting them connected to support and long-term services.”

Hernandez said that, if elected, she would not vote to hire any additional LAPD officers. Cedillo, in turn, has distributed fliers blasting Hernandez over some of her stances, including her support for the decriminalization of certain drug offenses, such as heroin possession. Those positions are “bizarre and dangerous,” the mailer said.

Hernandez, who lives in Highland Park, said she supports more treatment facilities and “safe” consumption sites for drug users. No one, she said, should be punished for drug use.

“We have sovereignty over our own bodies,” she said. “You decide whether you want to take your diabetes medicine. You decide whether you’re going to do chemo or even drink coffee.”

Times staff writer Kevin Rector contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.