Column: Some mentally ill people need to be forced into care. Newsom’s plan could finally help

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — Like too many people with mental illness, Chad Ricketts is on the verge of going to prison instead of receiving care. That’s the California way when it comes to treating serious brain illnesses, as pathetic as it is.

Hopefully, change is coming. More on that in a minute.

Ricketts, 25, has paranoid schizophrenia that first popped up while he was still a high school track star. It has grown progressively worse even as his parents, Patti and Dan Ricketts, have fought to help him into treatment. In January, he was stopped by police near his Simi Valley home for skateboarding in the street.

When they tried to put handcuffs on him, the paranoia kicked in, like it had during his three previous arrests, and he ended up on the wrong end of a Taser. One of the cops suffered a hand injury during the encounter, so now Chad is facing a felony charge and the possibility of joining the 30% of state prison inmates who are mentally ill behind bars.

It is a breaking point for his mother, who is so desperate to get Chad into in-patient treatment that she has even considered provoking her 6-foot-4 son into attacking her or his father in order to qualify for a mental health hold, a legal mechanism to force him into stabilizing treatment for a few days.

Let that sink in. Under what currently passes for our mental health care system, Patti believes pushing her son toward violence could be the best chance of saving him.

Patti says her problem is that Chad “won’t say he’s going to hurt himself and he won’t say he is going to hurt anyone else.” Despite being in a near-constant state of psychosis, despite the altercation with police, she said, that makes him ineligible for involuntary care.

For years, civil and disability rights advocates have argued against expanding the state’s authority to place people into conservatorships to force them into involuntary treatment — for mental illness or addiction or the combination that is so common as people self-medicate. Anyone who has ever watched “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” gets the gist of their argument. None of us wants to hand out one-way tickets to asylums, and personal freedom is the cornerstone of human dignity — even if it leads to bad choices.

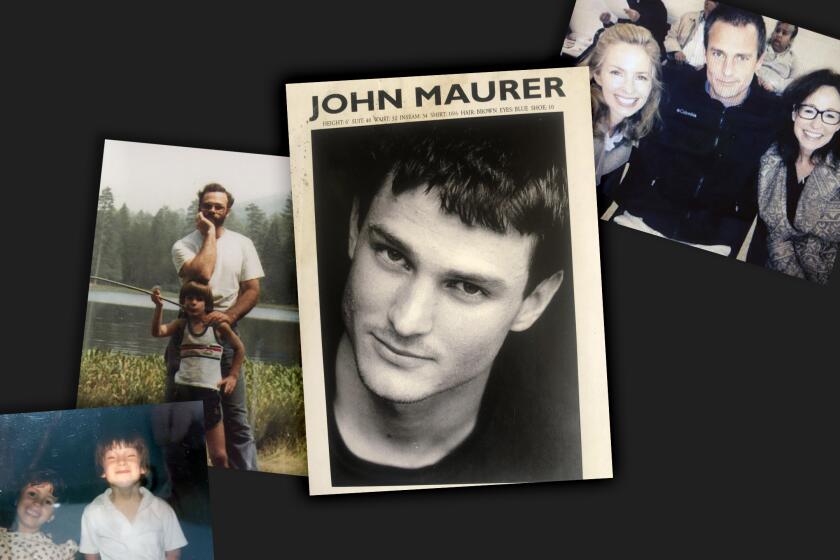

If anyone should have been able to escape homelessness, it’s John Maurer, whose siblings are prominent in L.A.’s homelessness and mental health systems.

But increasingly, people like Patti have been speaking out and pushing back — arguing there is nothing civil or moral about leaving their loved ones to fend for themselves, or leaving families like hers with no viable way to help. With today’s polarized politics, it’s a position that has been labeled conservative and regressive, and pitted against those who believe a harm-reduction, whatever-it-takes approach is better — that giving those with mental illness and addiction the time and safe space to accept treatment on their own terms is the right tactic. And often that does work.

On Thursday, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a framework that could help people like Chad and thousands of severely mentally ill people living on the streets, too ill to understand their own condition and resistant to help. It’s a workaround on the stalemate between those dead set against easier commitments and those who desperately want them.

Under the proposal, California would create “CARE Courts” (CARE is short for Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment) in every county to facilitate treatment for people with serious mental illness such as schizophrenia or psychotic disorders. It wouldn’t require criminal charges. Instead, family, first responders, outreach workers and others could start the civil proceedings — which would culminate in up to two years of court-monitored services.

It would also be available to those coming off short-term “5150” mental holds usually initiated by law enforcement. Unlike a conservatorship, a person referred to CARE Court would have agency in their treatment — it would be voluntary — along with a public defender and a support person, a role that disability rights advocates back as a type of mentor.

It is not, said Mark Ghaly, head of California’s Health and Human Services Agency, an expansion of conservatorships or a change in what qualifies a person for one. But those who fail to progress in the program could be referred for a conservatorship, with the presumption that there’s no suitable alternative — a sort of slow roll into involuntary care if all else fails. The governor’s office estimates between 7,000 and 12,000 people could qualify for CARE Court each year.

Gov. Newsom proposes plan to help homeless Californians with severe psychiatric, substance abuse and addiction issues get into housing and treatment.

Newsom’s proposal (which would have to be passed by the Legislature) also comes with the threat of punishing counties with court sanctions if they don’t step up with new and better treatment options, from community-based care to locked facilities. Right now, counties largely choose what they will offer and may choose to offer little, despite having millions to spend from multiple sources, including the so-called Millionaires Tax, otherwise known as 2004’s Proposition 63, which placed a tax on high-income earners to fund mental health care. This year, it’s expected to bring in about $3.8 billion. In the past two years, Newsom’s budgets have included about $14 billion for homelessness, with more than $4 billion of that tied to mental health. So there’s money — just no clear enforcement mechanism for ensuring counties use it to increase meaningful access to care.

CARE Courts are an important and workable idea that could help thousands — those such as Chad who are on the brink of a cliff, and those who have already gone over many precipices and seem crushed by the weight of their falls.

But it is also a concession to the hard line civil and disability rights advocates have drawn.

And in the background is the reality of California’s homeless and housing situation. We have more than 160,000 people on the streets, and it is estimated that at least a quarter of those — 40,000 — have mental illness. We also have rampant NIMBYism that has made it arduous if not impossible to build the shelters, transitional housing and, yes, locked mental health treatment centers that we need.

So Newsom’s plan is just the opening salvo in what is likely to be months of debate over where the right to be mentally ill ends and where society’s obligation to intervene begins. Should mental health treatment for our sickest residents be a state-mandated right?

State Sen. Henry Stern, who represents parts of Los Angeles and Ventura counties, thinks it should be — he’s introduced a short bill that would do just that. It reads like a placeholder for something longer to come, but Stern says it’s not. He wanted to keep it simple to introduce the concept.

In it’s entirety, Senate Bill 1446 reads, “Any person that lacks supportive housing and behavioral health care and is otherwise not living safely in the community has a right to mental health care services, housing that heals, and access to a full-service partnership model, including access to treatment beds and a recovery facilitator that shall navigate access to appropriate resources for the person.”

There can be tension between people with mental health challenges who want autonomy over their healthcare and medical providers or family members who believe it’s best to force treatment. How do the laws work, and how can people advocate for the best outcomes?

It doesn’t sound like much, but there’s a ton of innovation packed into that sentence — and a ton of controversy because it opens a backdoor for building housing (by requiring a place for people to receive treatment) and a front door for involuntary treatment. Similar to the “right to shelter,” it’s a right that would come with an obligation to accept help at some point (just as CARE Court would). It would also guarantee funding by the state because of the mandate (and would need federal approvals to revamp some Medicare rules).

Darrell Steinberg, the mayor of Sacramento and one of the driving forces to increase mental health services in California during his tenure in the state Senate, said CARE Courts are a “bold action.” He also strongly supports a right to treatment (though he hasn’t taken a position on the Stern bill yet).

“The law matters,” Steinberg said. “When society deems something important, we require it. People on the street need and deserve nothing less.”

Few understand the need for codifying how we treat severely mentally ill people better than Teresa Pasquini, who has a mentally ill son named Danny and who helped create the idea of “housing that heals” after decades of fighting for treatment. For her, housing that heals is shorthand for rebuilding a robust mental health system, one with all levels of care from an emergency service akin to 911 to long-term housing with whatever level of support is required.

The key is abundance, she said, instead of the scarcity that currently leaves people locked out of care. She believes that the harm-reduction approach is good for some, but not for those such as her son who can’t see their own conditions clearly — who may be “dead or in jail before that 39th outreach visit.”

“I am just kind of fed up with sloganeering,” Pasquini told me. “No wrong door. Full service partnerships. Whatever it takes. My son didn’t get whatever he needed and whatever it takes, even with a conservatorship.”

She told me she’s tired of involuntary commitments being a political “third rail” that prevents fixing the mental health system, and I think she’s right. Mental health is too complicated to assume that everyone will be able to make the choice to receive care, just as it’s too simplistic to think everyone should be required to jump into treatment the first time it’s offered.

I can’t imagine being a parent like Patti Ricketts, feeling like her own sanity is slipping away as she fights for her son. That California has left Patti, Dan and Chad isolated and falling deeper into the black hole of incarceration as treatment is unconscionable.

To Patti, that’s “insanity,” and it’s driving her family into crisis — there’s a fear that Chad will wind up homeless if he does avoid prison. It’s a constant, unbearable pressure on Patti and Dan that their son’s life depends on them, their patience and their resolve. Though he hasn’t hurt her yet, Patti says she is sometimes afraid of Chad. Sometimes she and Dan have to lock him out of the house. They know on some level they can’t handle this forever.

“We just have to live with it and it’s nearly impossible,” she said. “I know that everyone who has a mentally ill child feels this way.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.