Families struggle to get COVID tests to visit loved ones in nursing and senior homes

- Share via

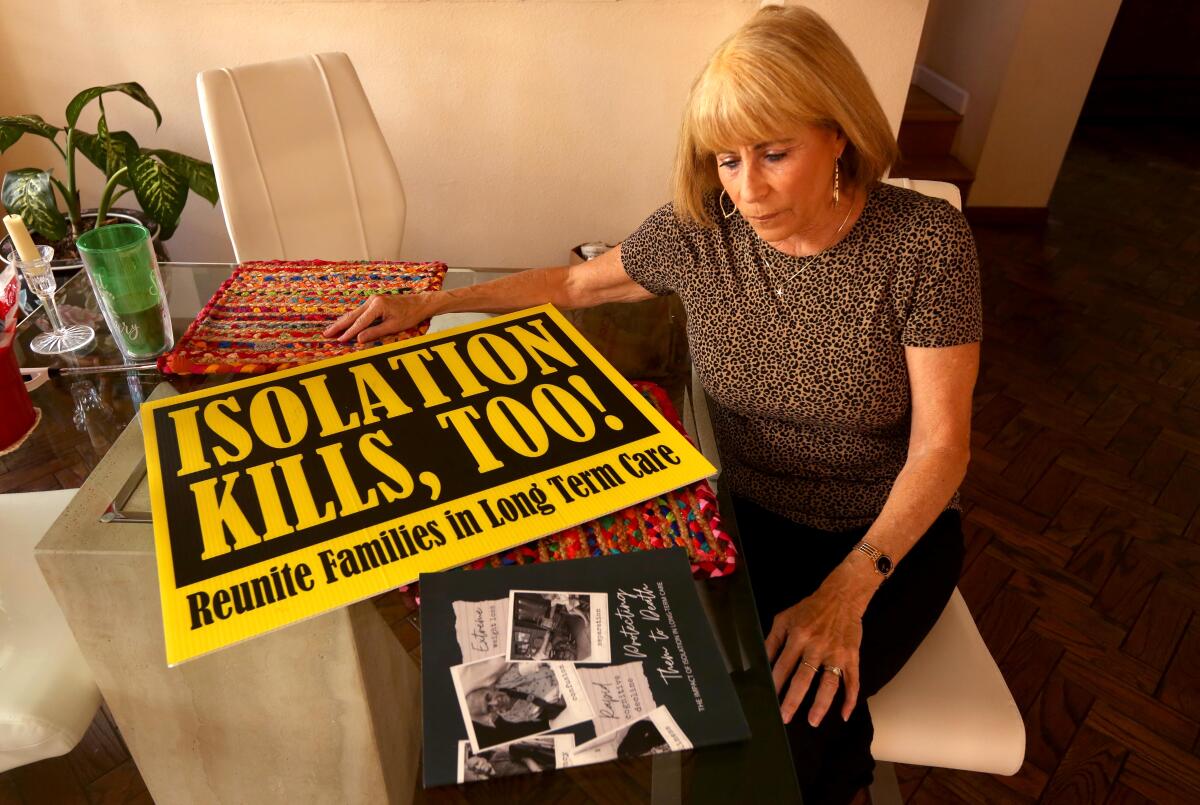

If Karen Klink wants to see her mother at the Redondo Beach memory care facility where she lives, she needs to hand over a negative test for the virus.

But as Klink hunted online for appointments for coronavirus tests last week, she kept coming up empty-handed. Rapid tests had vanished from store shelves in Hermosa Beach, where Klink lives. As she talked to a reporter, she clicked from site to site in frustration.

“There’s nothing available,” Klink said.

Facing a massive surge in coronavirus cases driven by the Omicron variant, California recently tightened the rules for visiting people in nursing homes, senior residential and other care facilities. Late last month, as coronavirus cases were skyrocketing, the state declared that nursing homes and other care facilities must require a negative test for COVID-19 for visitors — even for outdoor visits.

The new rules went into effect on Jan. 7 and will continue for at least a month. Under the state order, visitors must provide a negative result from a PCR test taken within two days or an antigen test done within a single day of their visit.

But for many people facing long waits, scarce appointments and sluggish turnaround times for PCR tests, “it’s been virtually impossible to get a test or test results back in that time frame in order to actually see your loved one,” said Tony Chicotel, staff attorney for California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform.

Rapid antigen tests can deliver a much swifter result once administered. But home tests have been costly and hard to find for many Californians. Private health insurers will soon be required to cover up to eight at-home tests a month, but many families have struggled to find them in stores or online.

Diary of a comedian trapped on cruise ship quarantine

“Testing people before they come and visit their loved ones is definitely a wise, science-based precaution,” said geriatrician Mike Wasserman, who leads the public policy committee for the California Assn. of Long Term Care Medicine. “The problem is the tests aren’t readily available to people.”

The California Department of Public Health said that while it understood the concerns, “we also recognize the importance of COVID prevention.” The state has established more than 6,000 testing sites, set up a website for Californians to find testing, and “put millions of at-home tests directly into the hands of local jurisdictions,” with more on their way, it said.

“We will continue our efforts to deliver more tests so families of residents, and their advocates, can continue to safely visit their loved ones,” the department said.

Critics have also argued that the rules are unfair because employees do not have to be tested as often. In L.A. County, for instance, nursing home employees must be tested at least once a week, according to a county order. Wasserman argued that staff should be provided rapid tests and required to test themselves at home each day before coming to work.

Federal data show that coronavirus cases are surging among both nursing home residents and staff, but the spike has been especially pronounced among staff, who have gotten COVID-19 booster shots at lower rates than residents.

Staffers have brought COVID-19 into care facilities, but “they’re not being subjected to the same protocol that they are enforcing upon us,” said Ozzie Rohm, a San Francisco resident whose father lives in a nursing home. “So what gives?”

In Los Angeles County, Klink eventually snagged an appointment for a rapid test that cost $25 so she could see her mother. But the ordeal has left Klink worried about how she will keep doing it over and over if she doesn’t have symptoms or hasn’t been recently exposed. Klink normally visits her mother two or three times a week.

In San Diego, Angela Trivonovich said she tracked down a rapid test at a CVS half an hour from her home. By the time she drove there and came back to the nursing home where her mother lives, the facility was about to shut down its front desk for the day. She insisted on staying to take the test and visit. Trivonovich, who usually visits her mother several times a week, spent another hour on Monday phoning libraries and drug stores to try to find more tests without success.

The state order says visitors who stop by on consecutive days have to provide a negative test only every third day, but Trivonovich worries that trouble finding tests will ultimately mean fewer visits with her elderly mother, who suffered months of delirium when her family was unable to see her in an Ohio facility.

“It’s another barrier,” said Pasadena resident Mercedes Vega, whose brother is in a skilled nursing facility. Her mother has sometimes waited hours in line to get tested, she said, which Vega herself couldn’t do between school and work.

Protecting people from the virus has to be balanced against their rights to choose to see loved ones, said Molly Davies, long-term care ombudsman for Los Angeles County. Seeing a child or spouse “may be a level of risk that they’re willing to take.”

In December, L.A. County issued an order telling nursing homes that any visitors who had not undergone COVID-19 testing before arriving should be given an antigen test at the facility.

Last week, however, the county updated that guidance to say that nursing facilities should provide tests to visitors “if possible.” When asked whether visitors would be turned away if the facility did not have a test for them, the public health department said visitors “need to have a negative test to enter.” Davies, the ombudsman, said her program has received complaints about facilities running out of tests or refusing to provide them to visitors.

Facilities are also frustrated, said Deborah Pacyna, director of public affairs for the California Assn. of Health Facilities. Some have been able to get rapid tests from health departments, she said, but some have none to offer.

Testing every visitor is “a commendable goal,” but if tests are unavailable, that means residents are not having visitors, and “we all know how harmful that’s been,” Pacyna said.

The California rules include some exemptions to the testing requirement, including for people visiting patients who may be near death. The new requirements come at a time when many families and residents have been pushing lawmakers to ensure better access to visitors at care facilities.

COVID-19 has pummeled nursing homes and other care facilities, but advocates argue that blocking visitation has devastated the mental and physical health of residents. Chicotel said that visitors are not only psychologically beneficial but also provide essential care and are crucial watchdogs for neglect.

Going months without visits from church friends, “I personally went into a very deep, deep depression,” said Nancy Stevens, 43, who has an immune disorder and has been living in a nursing facility in Rancho Mirage for more than two years. “I believed I had no support. That I was just forsaken.”

In San Diego County, Lynn Dedrick used to visit her mother every night at her Carmel Valley facility to try to ease “sundowning” — the confusion and agitation that can set in at dusk for people living with Alzheimer’s.

Dedrick would gently apply night cream to her mother’s face. They would choose clothes to wear the next day. Sometimes they would read books and talk about her father.

When the pandemic arrived, it “was a really cold, hard stop,” Dedrick said.

For nearly a year, Dedrick could not come in to see her mother, she said. She tried to greet her through a window, but her mother found it upsetting. By the fall, they could see each other outside at a distance, but “she just didn’t understand.”

The elderly woman lost weight and seemed withdrawn. When Dedrick was finally allowed back in as the pandemic eased, her mother told her that “every day she’d look and look and she couldn’t find me.”

Quarantines are cut in half, hospital workers allowed to return to work while still infected. Maybe Omicron changes all the game rules, but if so, someone should tell us.

In November, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services urged care facilities to let visitors in, emphasizing that “separation from family and other loved ones has taken a physical and emotional toll” on residents. The agency said facilities could no longer limit the length or frequency of visits or require advance scheduling.

Residents and their advocates complain California has not followed suit. In a December letter, California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform argued the state was violating the rights of nursing home residents by continuing to allow facilities to limit the length of visits. That was before the state tightened its testing requirement, which Chicotel called “tantamount to another lockout” unless facilities provide tests.

Advocates are also pushing for a federal law that would guarantee access for “essential caregivers.” The bill, H.R. 3733, would allow residents at nursing homes and other care facilities to choose two people to support them. Caregivers would have to follow the same safety protocols as staff and would be allowed in 12 hours daily during a public health emergency.

The American Health Care Assn. and National Center for Assisted Living, which represent care facilities, said they support the bill and welcome people “taking an active role in the care of their loved ones,” adding that it is “critical that anyone providing care in our facilities must undergo appropriate training and follow proper procedures.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.