- Share via

The moment had finally come for Kiana Portillo, a senior at Downtown Magnets High School in Los Angeles.

She had worked so hard and overcome so much to get to this point: an abrupt move from Honduras to Los Angeles as a fifth-grader, merciless teasing over her limited English and heavy Spanish accent, financial hardship and the emotional void left by an absent father.

But supported by teachers who tutored her over lunchtime and fed her intellectual hunger, Kiana had built a standout college resume: mostly A’s and rigorous courses heavy in math and leadership roles, including co-founding the school’s first feminist club.

Now she was about to submit her application to the University of California. But she couldn’t press “submit.” She froze at her laptop. Worries filled her mind.

Was she good enough?

•••

The 259 seniors in Downtown Magnets’ class of 2022 don’t take college for granted. They are the children of low-wage cooks and waitresses, parking valets and factory workers, caretakers and security guards. Their parents are mostly immigrants who landed in Los Angeles from Mexico, Guatemala, Nicaragua, South Korea, the Philippines, China — largely unschooled in how to navigate the U.S. college admissions process and unable to hire the pricey consultants and tutors enlisted by some well-heeled families to help their children gain an edge.

They represent the new generation of students reshaping the face of higher education in California: young people with lower family incomes, less parental education and far more racial and ethnic diversity than college applicants of the past. And Downtown Magnets, a small and highly diverse campus of 911 students just north of the Los Angeles Civic Center, is in the vanguard of the change.

Last year, 97% of the school’s seniors were accepted to college, and most enrolled. Among them, 71% of those who applied to a UC campus were admitted, including 19 of the 56 applicants to UC Berkeley — a higher admission rate than at elite Los Angeles private schools such as Harvard-Westlake and Marlborough.

This month, the Downtown Magnets applicants include Nick Saballos, whose Nicaraguan father never finished high school and works for minimum wage as a parking valet but is proud of his son’s passion for astrophysics.

There’s Emily Cruz, who had a rough time focusing on school while being expected to help her Guatemalan immigrant mother with household duties. Emily is determined to become a lawyer or a philosopher.

Kenji Horigome emigrated to Los Angeles from Japan in fourth grade speaking no English, with a single mother who works as a Koreatown restaurant server. Kenji has become a top student and may join the military, in part for the financial aid the GI Bill would provide.

“The main thing my kids lack is a sense of entitlement,” said Lynda McGee, the school’s longtime college counselor. “That’s my biggest enemy: the fact that my students are humble and think they don’t deserve what they actually deserve. It’s more of a mental problem than an academic one.”

What the students do have is a close-knit school community, passionate educators and parents willing to take the extra step to send them to a magnet school located, for many, outside their neighborhoods.

Principal Sarah Usmani leads a staff mindful of creating a campus environment both nurturing and academically rigorous; she has scrounged for money for a psychiatric social worker to help with mental health problems, an attendance counselor to stay on top of absences, an intervention counselor to monitor whether grades drop and an additional academic counselor.

And the students have McGee, who since 2000 has helped shepherd thousands to higher education.

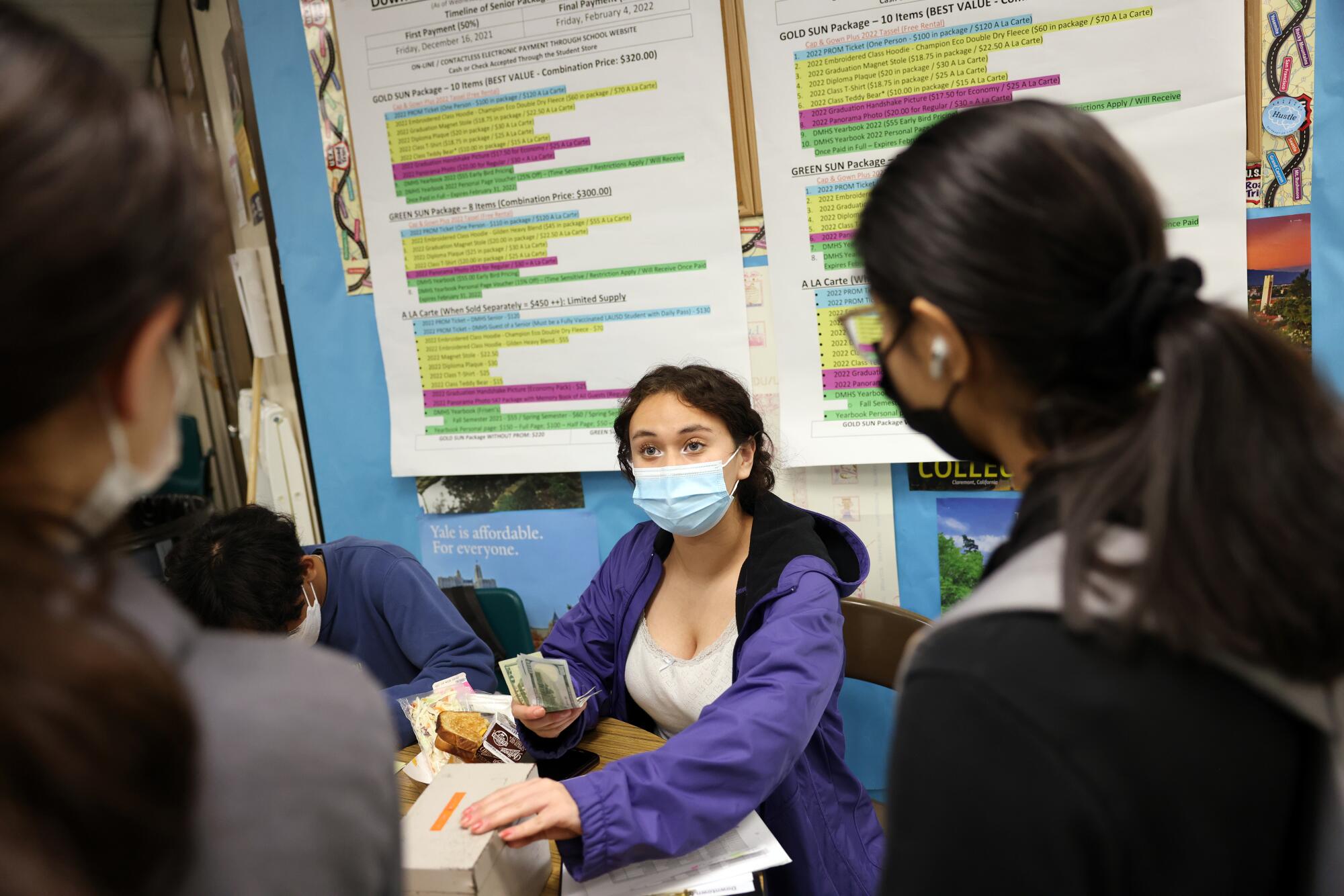

On a recent morning, students lined up to see her in the campus College Center, an inviting space with comfortable sofas, a bank of computers, colorful pennants and stuffed toy mascots from dozens of colleges.

Never mind that it was Thanksgiving break. UC and Cal State application deadlines were just a week away, and McGee’s students needed her.

Ms. McGee, I need a fee waiver! I’m not sure about a major. How do I figure out my weighted GPA?

“I can say no to evening, weekend and holiday work, but that means someone won’t go to college,” McGee said. “There are too many kids, good kids who will take themselves out of the process, and they’ll go to a community college with a 3.9. I can’t carry that guilt.”

By the numbers

Key facts about Downtown Magnets

McGee keeps close tabs on as many students as she can, often suggesting they consider options other than “the religion of the UC,” as she says many parents, particularly Asian Americans, regard the renowned public research university system.

It’s all about fit, she tells them. If you like personal relationships with faculty, consider smaller private colleges. Think about leaving California to stretch yourself. She gently nudges students with low GPAs away from pinning their hopes on hypercompetitive UCLA and Berkeley and suggests well-regarded but more attainable alternatives: Cal State Dominguez Hills, Woodbury University, Mount St. Mary’s College, Dixie State University.

But she also needs to make sure her top students are aiming high enough.

•••

The day before UC’s Dec. 1 deadline, McGee called Nick into the College Center to check in. The soft-spoken senior and his family live on an annual income of $30,000; at one point, when his father lost his job and the family faced eviction, they had to turn to relatives for help. His parents instilled in him an ethic to never waste — not money, not food, not college opportunities.

At Downtown Magnets, Nick entered the International Baccalaureate program, staying the challenging course when his friends dropped out. He tackled his weakest subject, English, by poring over Harvard professor Matthew Desmond’s exploration of evictions and poverty, to master academic language, text analysis and oral expository skills.

Physics is where Nick soars. His face lights up as he describes his hunger to unravel the mysteries of the universe: why it expands and whether it will stop; how stars become black holes.

Nick has earned a 4.47 GPA, making him the school’s fifth-ranked senior. He didn’t realize that until McGee called him in to tell him.

“You are in the top five, and this is a very competitive senior class,” she said. “If you want to apply to the Ivy Leagues, go for it! Know your worth, and give yourself the opportunities.”

Ivy League schools offer large financial aid packages that can make them cheaper than UC for low-income students, a point McGee amplifies by handing out lists of schools that meet full financial need without loans.

Nick had applied to UCLA, UC Berkeley, UC Irvine and UC San Diego, along with Stanford. But McGee’s encouragement expanded his thinking beyond top California colleges to the Ivy League.

“I didn’t think I could apply to the Ivy Leagues,” he said. “I didn’t have that much confidence. Hearing from Ms. McGee that I can, I’m going to try.”

•••

Aleyia Willis was considering attending a community college, but McGee told her the two-year system’s average completion rates are “just horrible” and encouraged her, instead, to apply to Cal State. Aleyia’s 2.9 GPA more than qualifies her for the Cal State system, which requires a minimum 2.5. She said her comparatively low GPA is due in part to her decision not to take Advanced Placement courses after failing the first one she tried, AP English, during junior year of distance learning. She was so upset after years of getting mostly A’s and Bs that she decided not to risk another failure.

That hasn’t distracted her from her ambition to become an art teacher. Her first choice is Cal State L.A., which offers both an art major and a teaching credential program; she also has applied to Dominguez Hills, Long Beach and Fullerton.

Aleyia’s parents both dropped out of high school but always pushed her to graduate. The 17-year-old, who has juggled school with as many as 20 hours a week of work at McDonald’s, said her college dreams are her own.

“I want something great for myself,” she said. “I don’t want a regular job; I want a career.”

Emily Cruz first caught McGee’s attention by the book she was carrying, a thick tome about Angela Davis, the passionate Black scholar and civil rights activist. That indicated a questing mind not reflected in Emily’s 2.9 GPA — too low to qualify for UC, which requires a 3.0 and generally admits students with close to 4.0 or above.

Emily said she started out fine, making the honor roll as a freshman, with a 3.5 GPA. But her grades — and mental health — tanked in sophomore year as the pandemic took hold and shut down the campus in March 2020.

Focusing on schoolwork was difficult at home, she said, because her mother often wanted her to help clean, cook and babysit, questioning why she was always on her laptop. She dropped out of the International Baccalaureate program, unable to juggle the competing pressures.

But she is a school leader, serving as class president two years in a row and appointed by administrators as one of three students on the leadership council, which weighs in on campus policies.

Emily now lives with her aunt, who she said is a fierce education advocate and gives her frequent pep talks about staying the course. She has applied to several Cal State campuses. One of her top choices, however, is Brandeis University in Massachusetts, a campus McGee recommended for its landmark transitional program of close academic support for underserved students with academic promise, leadership and resilience.

“Emily is wiser than her age, and her GPA does not reflect who she is,” McGee said. “UC is just going to say no, but Brandeis will take a risk for the right student whose life got in the way.”

•••

Kevin Hernandez also feels he came up short in his high school record but, like Emily, is undeterred from his college dreams. He recently joined more than a dozen students who came in to the College Center during Thanksgiving break to work on their UC personal statements. The all-important statements are the one part of the application where students can make their case for selection in their own voice, beyond grades, courses and extracurricular activities, UC admission directors say.

“What are the things you want a college or university to know about you that they might not otherwise already know based on what you’ve shared in your application?” said Gary Clark, UCLA’s director of undergraduate admission. “I think students think there’s this kind of gimmick or hook to essays. There really isn’t. It’s really just about telling your authentic story.”

Kevin’s story is captured in his responses to UC prompts. Writing about overcoming barriers, he described his worst school year: 10th grade, when his grades plunged from all A’s as a freshman to a D in Spanish.

The low grade raised painful issues of his identity as a Latino who can’t speak Spanish well and has been criticized for not embracing his culture. His mother, an Indigenous Zapotec from Mexico, did not teach him Spanish, and his Honduran father is not present in his life. His other male relatives have run into trouble, he said, leaving him without role models.

Despite that difficult year, which also included a C in AP history, Kevin rebounded in 11th grade and managed to end up with a 3.8 GPA. Yet the aspiring engineer knows that’s probably not good enough to get into UCLA, UC Berkeley or Harvey Mudd College, his top choices. He has also applied to several other UC and Cal State campuses.

“If Harvey Mudd gave me a chance, I will prove to them I can do it,” he said. “But what happens, happens. I’ve made peace with it. I had a terrible year, but I didn’t give up.”

In their UC statements, Kiana and Kenji both tried to flesh out their lives, but the 350-word responses could not come close to fully capturing them.

Kenji could not describe the pain of losing his father in second grade, feeling adrift and alone, struggling with a new language and culture in Los Angeles with his mother.

But he wrote about how his father inspired him to help others, including underclassmen with homework and church members with his handyman skills. And he wants to help his mother, who makes ends meet with her low-wage restaurant job, so he worked hard to achieve a 4.2 GPA and hopes to attend a good college without burdening her with debt. He is considering joining a college ROTC program, not only for the GI Bill benefits but also to help fast-track their path to citizenship and to find the male role models he hungers for.

For Kiana, being bullied by classmates over her limited English led her to take refuge in the universal language of math and to seek out teachers at lunchtime to press for deeper learning.

She gave up time for socializing and binging on Spanish-language TV to study English and got the language down in six months. She started winning academic awards and now has a 3.9 GPA — grades that did not suffer during the pandemic because she learned meditation, she wrote in her UC statement. Her mother supported her all the way, never letting on if money was tight for a single parent who was a dentist in Honduras but is underemployed here, in a medical assistant job.

“The language barrier taught me that I have the ability to overcome any challenge,” Kiana wrote. “It just requires confidence and perseverance, sparing no effort.”

And yet, for all her accomplishments, there she was, frozen, when it came time to submit her UC application. Was this a reach? Could her family afford it? Would she get good news or bad when campuses send out admission decisions next spring?

“I can’t do it,” she told her 13-year-old sister, Kyvana, who had come to her desk for candy.

“You can do it!” Kyvana said.

The sisters sat, staring at the screen. Finally, they pressed the “submit” button — together.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.