Take a trip through the magnificent department stores of old L.A.

- Share via

“Shop till you drop” did not always mean “shop till your phone drops from your trembling, bargain-hunting hand.”

For a very long while, “going shopping” in Los Angeles, especially for the holidays, meant putting on real clothes and shoes unsuited to a shower stall, and taking a ride — an adventure, really — to the showplaces of mercantile Los Angeles.

L.A. has been on this adventure for almost 150 years, through the peak-and-slide fortunes of the vast downtown flagship department stores, through the centrifugal spread of suburban malls, and the invasion of that unsightly moneymaker called the mini-mall — long before there was any internet to go shopping on.

Food and drink stores naturally came first; the earliest Ralphs grocery opened in 1873 in downtown, and Albert Cohn operated several branches of his fancy food shops. Dry goods stores, the forerunner of department stores, flourished too.

With the boom of the 1880s that inflated the city’s profile and standard of living, Los Angeles’ muckety-mucks wanted all that big, sophisticated cities had on offer too, and the great department store era was on. And if you think we are “over-stored” now, to use a market analysis phrase from the 1980s, consider the downtown shopping-scape of the 1880s and beyond, most of them clustered in the few blocks around 7th Street and Broadway.

The City of Paris department store, begun in the rough-and-ready 1850s as S. Lazard and Company, for Solomon Lazard. His bookkeeper/clerk and future partner, Eugene Meyer Sr., had come here from France and later took over the firm, renamed it the City of Paris, and sold it around 1883. His son, Eugene Meyer Jr., was born here, and Meyer Jr. eventually published the Washington Post — as did his daughter, Katharine Graham.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

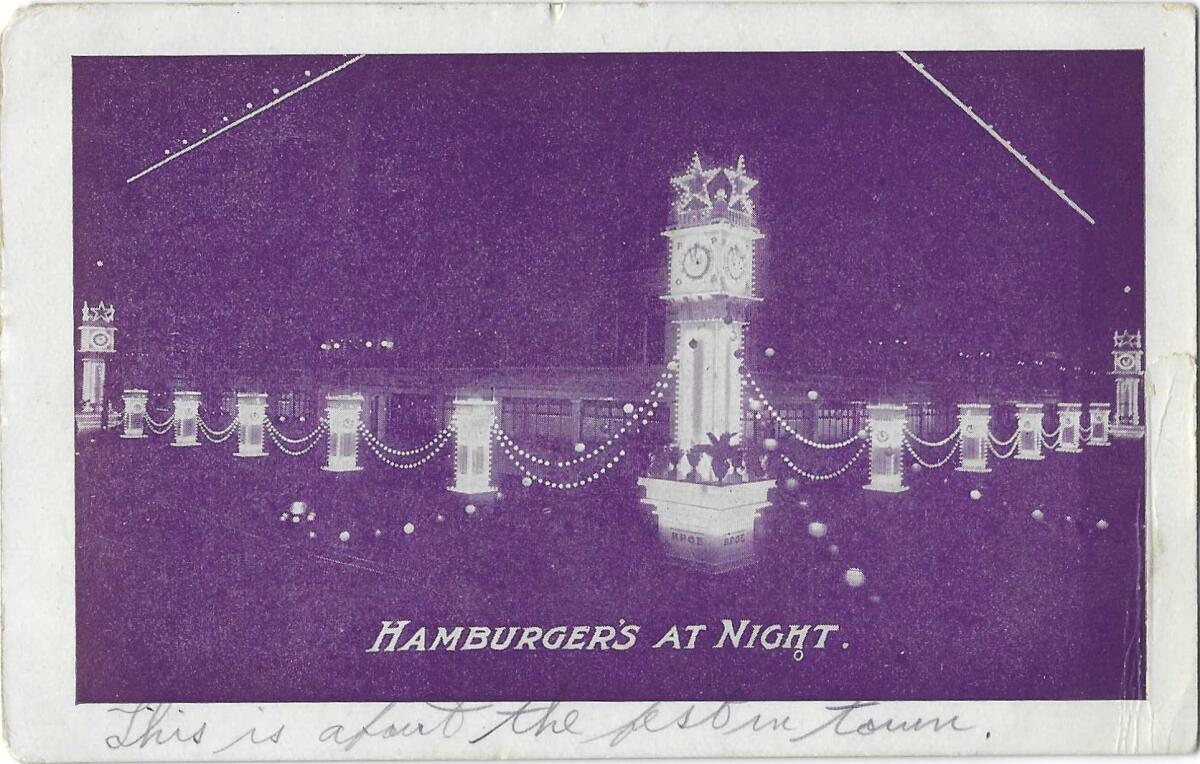

Hamburger’s

The immense, and immensely popular Hamburger’s, and A. Hamburger and Sons, originally “The People’s Store.” What was founded in 1881 as a modest general store on Main Street, with the novelty of no-haggling prices, soon had a stupendous five-story, half-block footprint. On an undated and unsent vintage postcard of the store, someone wrote in fine script, “This is our largest Department Store. They carry everything. It reminds me of Marshall Fields in Chicago or Wanamaker’s in N.Y.” — music to the ears of L.A.’s commercial aristocrats.

Those same aristocrats were at that point evidently too cheap to promote a purpose-built, publicly owned library building, so L.A.’s public library opened on the third floor of Hamburger’s in 1908. One new librarian, according to the city library’s own history, “was shocked to hear the elevator operators call out the library floors between the women’s wear and the furniture.” The library moved in 1913 to another rented space, but not before a young medical student who came in through the Hamburger’s entrance managed to smuggle an entire set of medical encyclopedias out of the library.

May Company

The May Company opened for business in Leadville, Colo., in 1877, selling Levi’s and long johns to miners. David May bought out Hamburger’s in 1923. In 1939, the best year for movies in film history, the architecturally striking May Company building opened on Wilshire Boulevard; it’s now the home of the Motion Picture Academy’s museum.

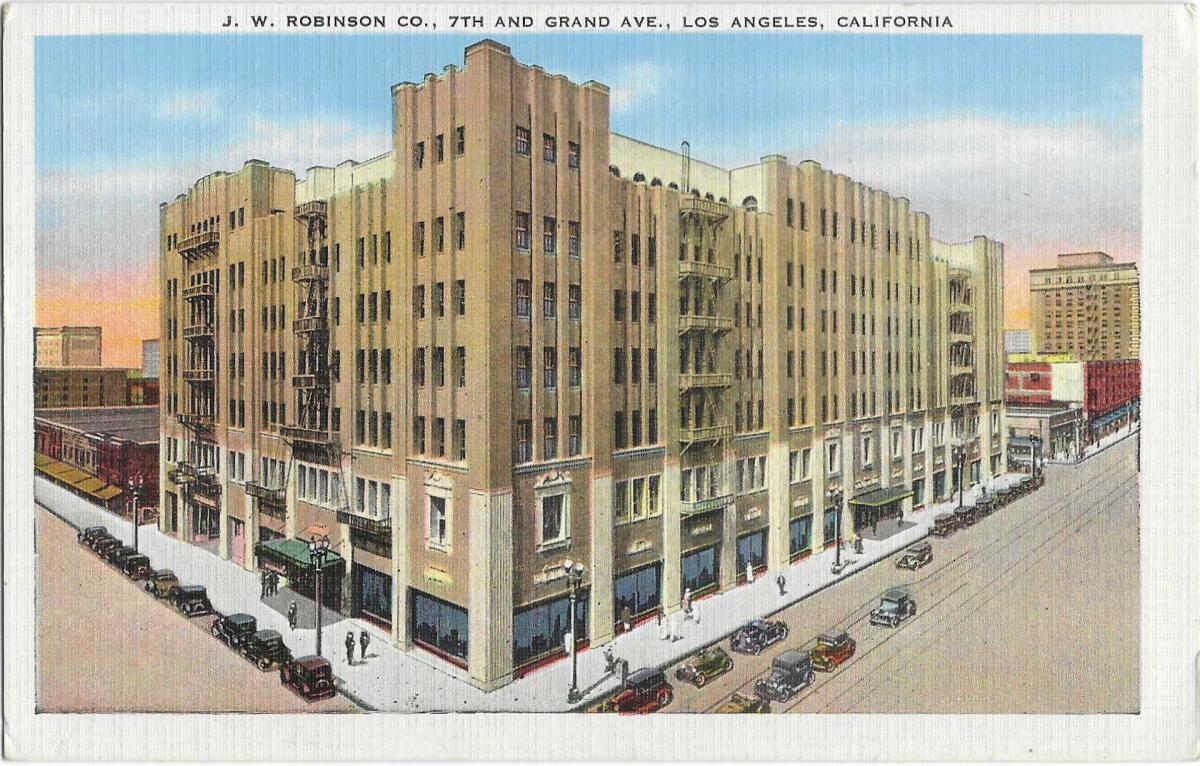

Robinson’s

Opened in 1883 at the corner of Spring and Temple streets as the Boston Dry Goods store, the renamed, grander store took the name of its founder, J.W. Robinson’s, moved to the fabulous, prosperous precincts of 7th Street in 1915, and in time became a powerhouse chain of branch stores.

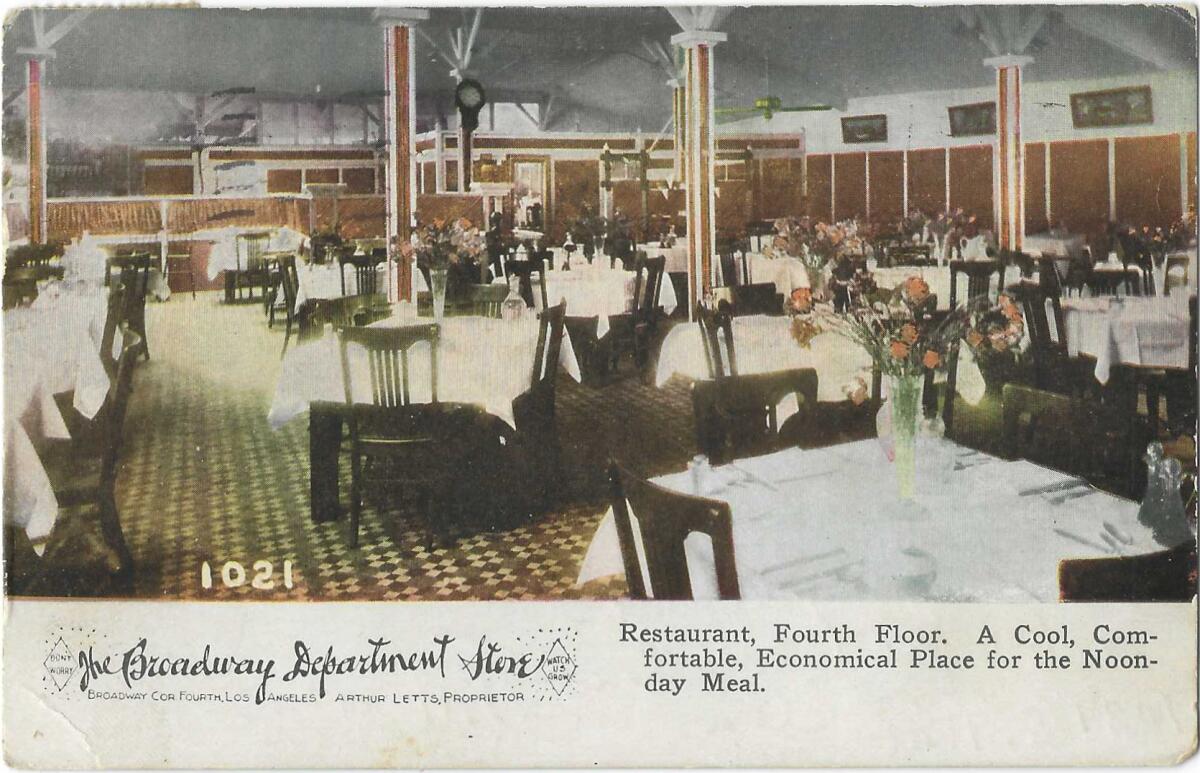

Broadway

The Broadway, flagship of a future chain, opened in 1896 downtown and in 1931 in Hollywood, where its stark rooftop sign “The Broadway Hollywood” still glows above Hollywood Boulevard, and where the store’s founder, Englishman Arthur Letts, built a vast garden, which was sold off and plowed under after Letts died, although some cacti were moved to the Huntington’s gardens. Letts helped to set up one of his employees in business with another store, known by that man’s name …

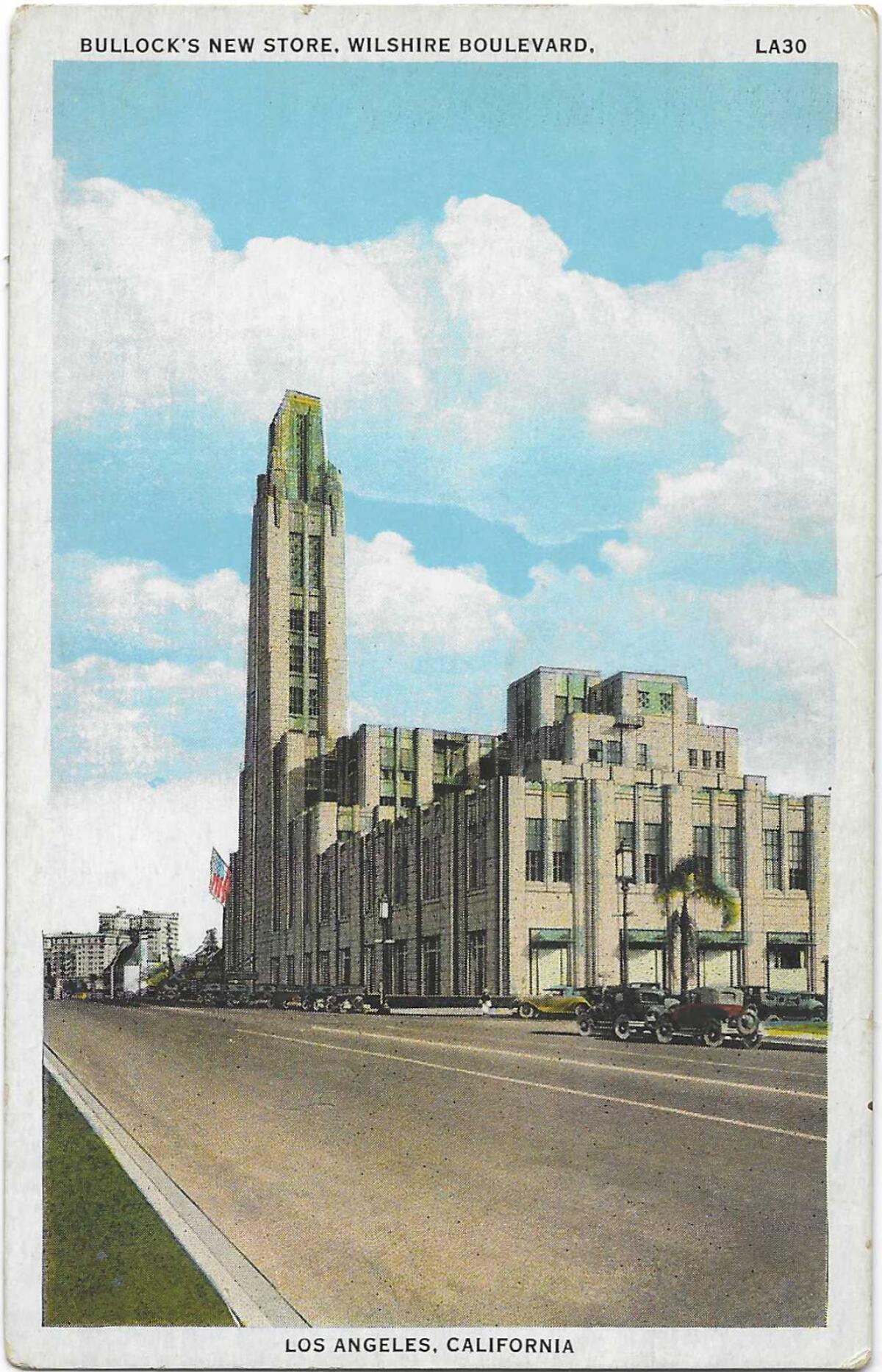

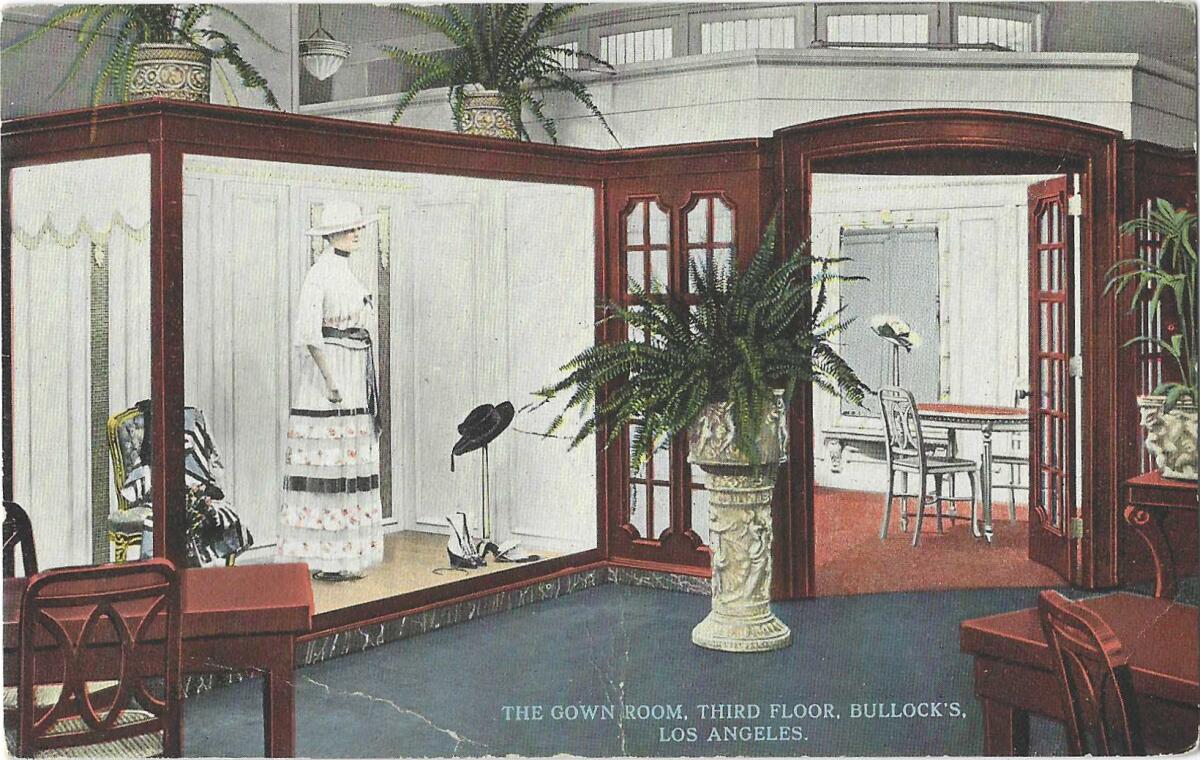

Bullock’s

… Bullock’s. Perhaps the department store name most associated with L.A., the first store opened in 1907 downtown, and in time Bullock’s had about a score of stores across Southern California, including the Pasadena and Westwood stores, which crafted their own clothing labels. The most spectacular was Bullocks Wilshire, an Art Deco masterpiece and the surviving anchor building for the pre-World War II glamorous Miracle Mile shopping district — its developer longed for it to become the “Fifth Avenue of the West.”

At some point in the 1970s, its name lost the apostrophe used by its lesser sisters. It was the most sublimely elegant and beautiful department store in California, as proved when, years in the future, the new owner, Northern California Macy’s/I. Magnin, made off with fixtures from the historically significant 1929 building, and had to bring 166 of them back. It carried the most opulent lines of clothing and luxury goods in the world, and even the impoverished hoi polloi like me could walk around its vitrines with the appreciation you’d give to a museum, which is how carefully the objects were displayed. The vendeuses, as chic as their Parisian counterparts, once included young Angela Lansbury. And future First Lady Pat Nixon, as a college student, was a Bullocks Wilshire assistant buyer (phone number Fitzroy 5212). The store’s true entrance wasn’t on Wilshire but through the drive-up porte-cochere behind the store, its ceiling ornamented with a mural called “The Spirit of Transportation.”

It is now Southwestern Law School. As for the “Fifth Avenue of the West,” it was for a time so promising that in 1962, the Japanese department store Seibu opened a branch at Wilshire and Fairfax. It closed two years later because, an executive VP explained, to keep going, it had to “carry merchandise that weakened the identity” of its Japanese brand. The Petersen Automotive Museum stands on the site now.

Buffums

Buffums — which also once had and lost an apostrophe — was a Long Beach-based store that set itself up in business in 1904 and in time opened more than a dozen branches from San Diego to Glendale. Its most famous family member was Dorothy Buffum Chandler, “Buff,” the wife of Times publisher Norman Chandler, and a vigorous philanthropist and civic leader who dreamed and muscled the Los Angeles Music Center into existence.

“Them: Covenant” on Amazon Prime is a reminder of the all-too-common housing covenants that restricted who could buy homes in certain neighborhoods in Compton, around Southern California and elsewhere. Determined Black people over the decades fought for their rights to live where they pleased.

Ville de Paris

The Ville de Paris store, founded in 1893 on the site of today’s Grand Central Market by Auguste Fusenot, one of the great wave of French immigrants who brought their wine-grape stocks and stylish tastes to town. Fusenot died on a trip to his native France and is buried in Pere Lachaise cemetery, also the resting place of an even more renowned Angeleno, Jim Morrison. During World War I in 1918, a year before the original store was sold, actress Sarah Bernhardt visited L.A. and showed up at a Red Cross fundraising bazaar and fete organized by the department store.

The food and clientele

No one had to go hungry in these cathedrals of commerce. I do not mean the salty, sugary excesses of a food court. Into the 1980s, the flagships and many of the satellite stores had dining rooms and tea rooms; Buffums maintained 11 restaurants, individually done up as a villa or a barn or a Mexican terrace. Restaurants in the Neiman-Marcuses in Newport Beach and Beverly Hills had full bars, as did the Robinson’s in Beverly Hills, and several May Company pub-themed restaurants. The blue-appointed restaurant at the May Company’s grand Wilshire Boulevard store was swagged in velvet curtains and lighted with enormous Italian chandeliers.

The ne plus ultra, though, was the Bullocks Wilshire tea room. The store sent models swanning through the tea room in the latest for-sale styles as guests chose from a ladies-who-lunch menu whose dishes bore names like the Wilshire Tower. At lunchtime and tea time, the salmon-and-green wallpaper was privy to the lip-smackingest high-society gossip.

California-based chains considered their customers and their markets; they did not have to knuckle under to the marketing dictates of a distant headquarters. New York stores may start stocking winter coats in August, but in Southern California, where it can reach 90 degrees in November, local stores could meet local needs. For decades, then, the glories of so many stores with so many distinct personalities, and an economy with its foot on the accelerator demands, put recreational shopping high on the list of Southern California’s de facto hobbies.

The decline of the department store

Then, almost all of this came to grief. Changing shopping tastes and opportunities, and the junk-bond takeovers and consolidations, collapsed the emporium empires in on themselves, in a tombstone roll call of L.A.’s commerce history.

In the 1970s, big discount stores began to siphon away some part of the department store trade too. One was the now-extinct Zodys chain — what is it with store names and the elusive apostrophe? — with a branch on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood. Long years ago, I was interviewing Vincent Miranda, the owner of the Pussycat porn theater chain. He was showing me around his neighborhood near Western Avenue and Sunset, and telling me how responsible he was being careful not to put X-rated posters in the street-side display cases of his theater where kids might see them. And then he flipped his hand toward the big discount store down the street. This neighborhood has gone to hell, he railed, “ever since that Zodys went in.”

In 1992, Robinson’s and May Company stores became Robinsons-May, and the sum wound up as far less than the total of the parts. In 2005, that partnership was dissolved when many stores were closed and the survivors became Macy’s or Bloomingdale’s — or nothing, depending on the market.

In 1988, Macy’s took over Bullock’s, Bullocks Wilshire and I. Magnin, and Bullocks Wilshire was quickly rebranded to no apparent effect or purpose as I. Magnin. The place was ravaged by the 1992 riots and never really got back on its feet under either name.

In 1995, Federated, the department store chain with an appetite like Gargantua, had already taken over Macy’s. Now it gobbled up the Broadway stores and sold off some, closed some, and slapped “Macy’s” or “Bloomingdale’s” on others. It flipped its 21 Bullock’s stores to become Macy’s. Between that and the Nordstrom chain’s southward reach from Seattle, Southern California’s landmark retail stores were completely homogenized and colonized.

Well before that happened, though, postwar L.A. was reveling in having money to spend, and it wanted to spend it closer to home, in places it could park all of its big new finned-mobiles.

Suburban shopping centers decentralized the nucleus of downtown shopping, with name department stores anchoring malls like the pioneering one in Lakewood, opened in 1951 — a from-scratch shopping universe crafted for the from-scratch community of Lakewood.

The original Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza opened in the plush, flush year of 1947 with a Broadway store and a Woolworth’s, to be revised and relaunched in 1989. At the 1980 Sherman Oaks Galleria, a Robinson’s and a May Company bookended the plaza’s “lifestyle” vibe that became the entire joke in movies such as “Valley Girl” and “Fast Times at Ridgemont High.” The galleria was hammered by earthquake and recession, and it has joined the queue of malls being reconfigured again and again for this century of recession and pandemic, many of them inviting out-of-the-retail-box businesses like medical clinics and even hotels.

California’s Legislature spent part of its Sacramento time this year wondering whether to turn rattlingly empty shopping malls and big-box stores into housing, which would mean butting heads with local governments that get more out of sales taxes than property taxes.

What was life like on Dec. 6, 1941, and in the years before then for one group of people for whom Pearl Harbor would drastically alter their lives — the Japanese and Japanese Americans in Los Angeles?

And now we come to the hiss and boo section: mini-malls. Or, by another name — a name that sounds satisfyingly louche — strip malls.

Almost everyone hates them, but almost everyone uses them.

And they didn’t start in the stucco-mad ‘70s, either. The forebears of the mini-mall were the drive-in stores of the 1920s: Glendale’s first drive-in market, in 1924, and the 1929 Chapman Plaza, a Spanish-revival building that still stands, in Koreatown. It was designed especially for cars to zip in and out of a pretty central courtyard ringed by shops. That courtyard also had fountains and gardens — not what you find in modern-day mini-malls. The lamentably departed Mandarin Market in Hollywood was ornamented with pagodas and a tall, swooping electric arrow pointing drivers to its shops.

If modern mini-malls had some architectural finesse, maybe we wouldn’t hate them so much. In 1989, 10% of respondents told a Times quality of life poll that mini-malls were their biggest gripe. In 1987, my veterinarian’s wife got arrested for refusing to come down from the roof of a historic Eagle Rock building to protest its being knocked down for a mini-mall. In a 2014 book called “Street Level: Los Angeles in the 21st Century,” writer Rob Sullivan pans the strip mall for its “squat sameness [that] has spread like teenage acne across the surface of urban, suburban, and rural America.”

Despite bans and limitations, mini-malls’ lasting presence can be laid in part to the fact that they are an affordable starting point for immigrants opening restaurants or businesses that would be unaffordable in a grander retail setting.

My favorite mini-mall story is, I admit, a schadenfreude one. Two best friends started up a mini-mall development company, chose the name “La Mancha,” from the Broadway musical about Cervantes’ rickety hero who tilted at windmills thinking them to be giants. Because of the song, they thought “la mancha” meant “impossible dream” in Spanish. Instead, as they found out later, it means “the stain.”

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.