- Share via

Glenda Valenzuela plopped some canned beans into a pan of sizzling onions — breakfast for her husband and three young boys.

She grabbed a bag of white beans to wash and dump into a slow cooker.

That batch would be for lunch. More beans were on the menu for dinner. And for breakfast the next morning.

Once, Valenzuela and her husband, Mario Alarcon, worked full time cleaning offices, schools and other buildings. With money from side gigs, they could take their children to a buffet or a movie night including popcorn and drinks.

They dreamed of more: a bigger home in a neighborhood where their autistic eldest son could have better services and where Alarcon could expand his entrepreneurial spirit.

It all seemed within reach for two immigrants without legal status — until the COVID-19 pandemic descended.

Now, a $10 bill hidden at the bottom of Valenzuela’s purse can feel like a godsend.

::

Alarcon and Valenzuela met on a camping trip at the Kern River in 2010.

He was from Veracruz, Mexico. She was from Guatemala City.

Alarcon had come to Los Angeles at 17, hoping to save the money he earned at restaurant and janitorial gigs for a computer engineering degree back home. She was fleeing an abusive relationship.

They made a life in L.A. together. Their first son, Angel, was born in 2012. Daniel came two years later.

They both had cleaning experience, so they started working for a company that contracts with office buildings.

As a second job, Alarcon repaired furniture for an antique store in San Marino. He had learned the craft by watching his father in Mexico. The pay was $22 an hour, versus the $13 an hour he earned cleaning.

Six days a week, Alarcon worked an 8:30-a.m.-to-5:30-p.m. shift at the furniture store, then headed to the Department of Motor Vehicles in El Monte or an architect’s office in Burbank, where he cleaned until midnight.

On weekends, he repaired tables, chairs and dressers for clients he had met through the furniture store. That didn’t leave much time with his family. But he beamed when he realized how much he and his wife had earned — almost $55,000 in 2018 and again in 2019.

It was a blessing, especially after learning they were expecting their third child.

They were able to pay the bills and their $1,300 rent, even splurging on matinees at the Highland Theatres for $3 a head.

When Angel and Daniel asked if they could go to Chuck E. Cheese, saying “yes” wasn’t hard.

In 2019, when their minivan broke down, Alarcon bought a new $30,000 car on credit. The payment was more than $600 a month, but with good budgeting, they could manage.

It was a silver 2020 Honda Accord with five seats, just enough for their family, though not big enough to transport his client’s furniture. For that, Alarcon borrowed a friend’s truck.

They hired a lawyer to achieve their dream of citizenship, paying the fees with their modest savings.

That October, Alfredo was born.

Valenzuela’s final residency hearing was scheduled for spring 2020.

::

In March 2020, office workers around the country were sent home.

The building lights were shut off. Cubicles covered with family photos and stacks of paperwork, dried up succulents and Happy New Year’s messages were frozen in time.

They had endless Zoom meetings in makeshift home offices. Many struggled with isolation.

But they had the freedom to set their own hours. They saved money on gas and spent less time commuting. Some moved out of the city, leaving their expensive rent behind. They kept collecting their salaries.

The janitors weren’t so lucky.

With offices empty and events canceled, at least half the Service Employees International Union’s 100,000 or so janitorial workers in California — toiling in strip malls, entertainment venues and offices — either lost their jobs or had their hours reduced, said David Huerta, president of SEIU United Service Workers West.

Before the pandemic, Alarcon’s bosses at the furniture store had laid him off after learning about his weekend jobs.

Then in March, as office workers sheltered at home, Alarcon’s cleaning hours were cut. His furniture clients, fearful of contracting the coronavirus, stopped calling him too.

Alarcon went from working 16-hour days at three gigs to just four hours a day at the DMV. Valenzuela was laid off entirely.

Her residency hearing was postponed to 2022, and her work permit expired. She couldn’t afford the $1,000 to renew it, so her unemployment benefits lapsed.

The family fell behind on everything — rent, car payment, electric and gas bills.

“I’m very Catholic. I pray a lot. Every day I give God thanks that we’re alive. So many don’t have a roof or food to eat.”

— Glenda Valenzuela

They canceled the at-home entertainment, like Netflix and cable TV, that made pandemic life bearable for wealthier Americans.

They bought an antenna to watch some TV channels and switched their iPhones to a more affordable plan.

They became regulars at food pantries and got rent money from local nonprofits.

Valenzuela pawned her jewelry — gold chains, earrings and rings — retrieved it, then pawned it again.

The family took another hit around Christmas 2020 when all five got sick with COVID-19.

The San Joaquin Valley never fully recovered from a summer COVID-19 surge driven by the Delta variant. The rural, agricultural region continues to be hard-hit by the virus.

They believe that they were infected at the grocery store, or that Alarcon contracted it at work.

Valenzuela couldn’t stop to rest. She had her boys to take care of. As she breastfed her feverish baby, she worried she was hurting him.

“I’m not going to die,” she told her husband. “I’m not going to let you or my kids die.”

Alarcon lost 40 pounds. Walking from the living room to the bedroom left him short of breath.

He didn’t work for two weeks. The cleaning company paid him anyway, but he had to suspend his furniture repairs.

A year and a half after losing most of his steady work, even as Alarcon has become increasingly resourceful in his side hustles, they still can’t catch up on rent. They’re always a month or two behind.

::

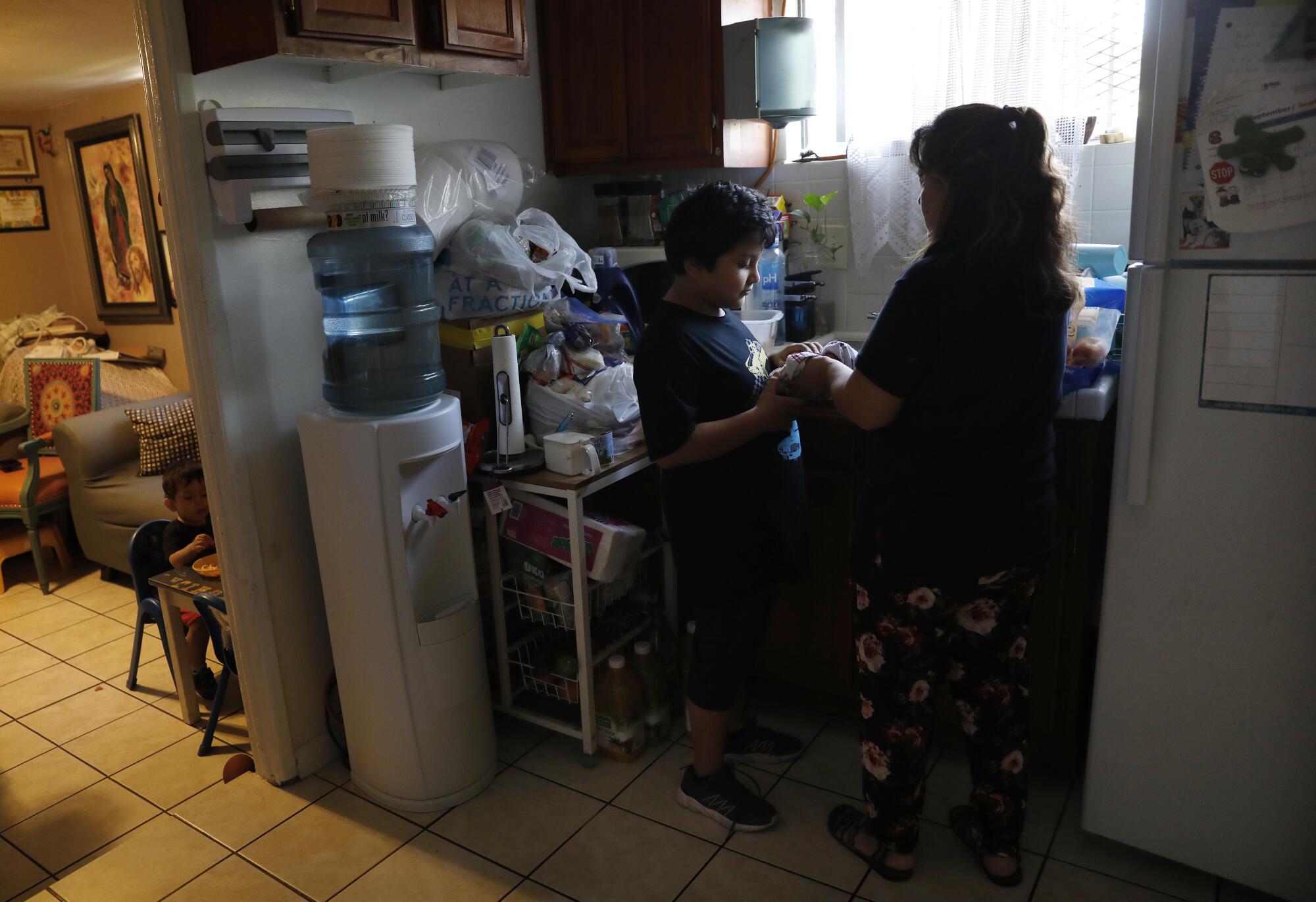

They live in a small back house on busy Monterey Road in Montecito Heights.

Their slice of the driveway is covered with tarps so Alarcon can work on his furniture.

Above the family couch, a painting of the Virgin Mary cloaked in green hangs in a gold-trimmed frame. Jesus is at her side.

On a recent weekday, a sleepy Angel, 9, emerged from his bedroom, greeting his parents with a smile.

“Bebe, vas a comer?” his mother asked — was he hungry?

She gave him two choices — beans with tortillas or waffles?

“Frijoles,” Angel answered.

From the living room, 2-year-old Alfredo let his mom know he wanted agua.

“I got all of this from a food bank,” Valenzuela said, gesturing to her stash of beans, rice and pasta. “And thank God, because I had run out.”

Feeding three boys with donations and food stamps isn’t always easy, said Alarcon as he played with Alfredo.

Daniel likes sandwiches with two slices of American cheese and ketchup. Angel doesn’t like different types of food touching. Spaghetti is usually a safe bet.

Half of their large dining table is covered with fruit bowls, napkins, religious candles, angel figurines and another virgen, Our Lady of Charity, crowned and dressed in blue.

In their tiny apartment, there is no other place to put these items. Valenzuela prays for the day she’ll have enough space to share a meal with her whole family.

For now, they take turns eating, or sometimes the boys eat at a tiny blue children’s table in the living room.

“I’m very Catholic. I pray a lot. Every day I give God thanks that we’re alive. So many don’t have a roof or food to eat,” Valenzuela said.

The little blue table is also where Angel, Daniel and Alfredo sometimes receive therapy for their special needs.

First generation trauma is an emerging term in the Latino community, with people talking about it on social media. Here’s how it affects children of immigrant parents.

Angel looks after his younger brothers diligently. He is obsessed with the Titanic, getting excited when anyone brings up the subject.

But he struggles with his speech, sometimes mumbling things only his parents understand. Staying focused and getting good grades is hard without consistent practice.

Daniel’s doctors suspect he has mild autism and have suggested therapy for speech and behavior problems.

Alfredo is too young to receive a diagnosis, but his limited speech signals that he may be autistic too. Therapists play games with him and chat in Spanish and English.

This care is free through the children’s Medi-Cal — the state’s Medicaid program. Valenzuela receives an $800 monthly disability check for Angel, which often goes toward their rent, clothing and toys.

“Sometimes people ask us how we do it — how do you survive with all our bills and debts?” Alarcon said.

The money he earns from an assortment of side jobs helps.

A friend who asked Alarcon for help booking a flight to El Salvador paid him $50. “I do the whole transaction,” Alarcon said. “I check in for him from home, everything, as if I were his travel agency.”

Other times, Alarcon makes coronavirus test appointments or does computer repair work for friends in exchange for cash. He keeps an eye out for jobs on service apps like DoorDash.

“It’s infuriating, the people who don’t want to get vaccinated. It affects us, because as long as we’re not vaccinated, the pandemic won’t end. If things close again, we’ll be worse off.”

— Mario Alarcon

And he swallows his pride to make money in ways he never thought he’d have to, such as taking home empty bottles and cans from DMV trash cans to recycle.

In his living room earlier this year, Alarcon held up his phone to show off his DoorDash earnings: $504 in one good week. Almost enough for their car payment.

But with soaring gas prices, delivering meals isn’t profitable anymore.

Valenzuela and Alarcon often sit at their dining table, bills sprawled in front of them, to discuss their finances.

The boys need new clothes. Should they use a credit card? What can they go without that week?

It feels as though their money is going through a revolving door, the debt not decreasing and not increasing.

They pay $1,300 in rent, $612 for the car, $120 for their phone bill and $135 on insurance, plus gas, electricity, internet and other expenses. Each month, Valenzuela sends about $200 to Guatemala to cover her mother’s rent.

They have about $3,000 of debt on credit cards from stores such as Burlington Coat Factory and Harbor Freight Tools, where they buy clothes for the kids or tools for Alarcon’s furniture repair.

They also owe about $7,000 on a loan to cover hospital and funeral expenses for Valenzuela’s father in Guatemala. He died of pancreatic cancer in April.

Now, when Angel and Daniel ask for McDonald’s, the answer is usually “no.”

Even free trips to places like the beach give their parents pause. There’s parking, plus whatever the boys might crave while they’re out.

“We can’t give ourselves the luxury of spending money just like that,” Alarcon said. “We have to make magic with the numbers.”

They pray to God that more people will get vaccinated.

“It’s infuriating, the people who don’t want to get vaccinated. It affects us, because as long as we’re not vaccinated, the pandemic won’t end,” Alarcon said. “If things close again, we’ll be worse off.”

Even after the pandemic ends, office employees are likely to continue working remotely.

In many households where work circumstances differ widely, the pandemic has raised difficult questions of privilege and equity among family members.

Those who clean up after them, emptying trash cans and vacuuming floors, may never see their jobs fully return.

::

With the world slowly reopening nearly two years into the pandemic, Valenzuela has felt little relief.

Her two eldest boys have been able to return to school. But to be available for their therapy sessions, she had to turn down cleaning jobs with hours that weren’t flexible enough — and paid just enough to cover a babysitter.

On top of everything else, a numbness in half of her face worsened after she got COVID-19.

COVID-19 vaccination rates are significantly lower among L.A. County’s younger Black and Latino residents than for other racial and ethnic groups.

Doctors offer no diagnosis. They just tell her to do the impossible — relax.

On one of her most desperate days, she didn’t have money for diapers or milk — “not even for a single egg.”

Alarcon is the more optimistic one.

“Don’t worry,” he says. “Something will come.”

Just then, his phone rang. It was a client who wanted some chairs fixed. She sent him the payment that day.

“Did you see the deposit?” Alarcon told his wife. “Something came, you see?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.