First-ever redistricting commission to draw boundaries for L.A. County supervisors

- Share via

For as long as anyone can remember, the Los Angeles County supervisors have drawn the boundaries for their own districts.

In the 1980s, the all-white board was not inclined to create a district favoring a Latino candidate.

Only after a lawsuit did Gloria Molina become the first Latino supervisor in 1991.

This year, for the first time, an independent commission will decide which parts of the county are grouped together for the purposes of electing a five-member board that sometimes flies under the radar but controls a vast bureaucracy and a $36-billion budget for the nation’s most populous county.

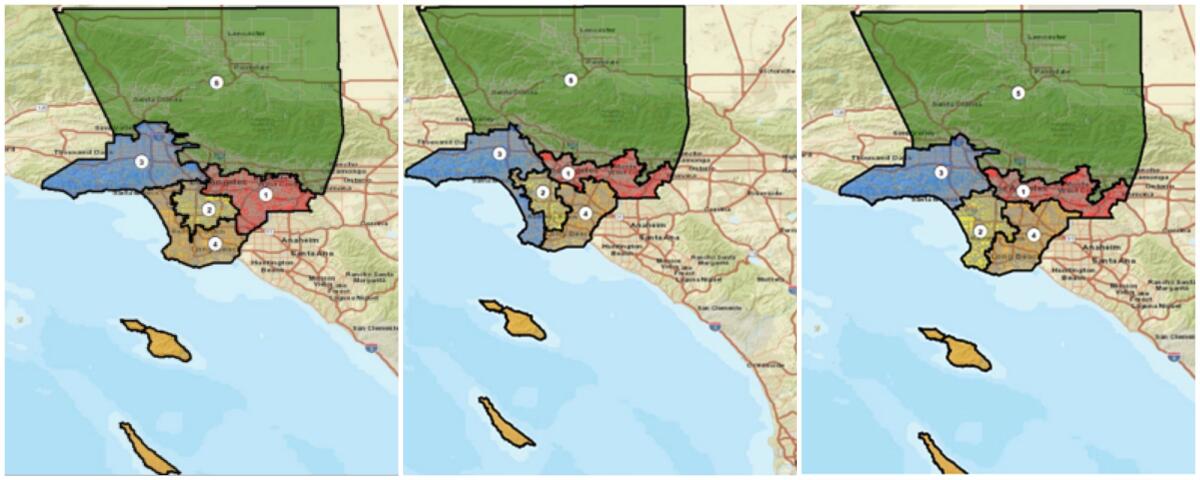

After more than a dozen public hearings around the county, the 14-member commission has narrowed its options to three maps and is set to choose one by Dec. 15, in a redistricting process that occurs once a decade following the U.S. census.

Each map would create a second district with a large Latino voter population, in addition to the district Molina won, which is now represented by Supervisor Hilda L. Solis.

But Black and Asian voters would be grouped differently in each map, in a county that is 49% Latino, 26% white, 15% Asian and 9% Black, affecting the political power of each constituency and drawing close scrutiny from advocates.

The commission was created by a state law passed in 2016 that aimed to give Latino and Asian residents a better shot at representation on the L.A. County Board of Supervisors.

L.A. County sued, claiming that a law targeting only one county violated the state Constitution, but lost on appeal last year.

“It took a lawsuit to elect the first Latino supervisor, and it took a state law to change this broken system where the powerful few protect the status quo over the will of millions of voters,” Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara, who authored the bill as a state senator, said in a statement. “Representation matters, and my motivation was that the process of drawing lines reflect the diversity of the nation’s largest county including our Asian American residents.”

It has been 15 years since there was a Latino representative on the five-member board, which oversees a roughly $7.5-billion budget.

The three proposed maps could still be adjusted before the Dec. 15 deadline.

One of the maps concentrates many Black and Latino voters in the 2nd District, now represented by Supervisor Holly J. Mitchell and previously by Mark Ridley-Thomas, both of whom are Black.

Another proposed map extends the 2nd District to the ocean, lumping South L.A. with coastal communities, which arguably dilutes Black voices and makes it more challenging for a Black candidate to win.

Community Coalition, which is based in South L.A. and advocates for both Black and Latino residents, is among the groups supporting a third map that would leave the 2nd District with about 30% Black voters.

This map, which evolved from one submitted by a coalition of almost 30 community organizations called the People’s Bloc, would remake Supervisor Janice Hahn’s 4th District into a second Latino district.

The beach cities from Marina del Rey to Long Beach that Hahn now represents would join Supervisor Sheila Kuehl’s 3rd District, creating a coastal band stretching north past Malibu to the Ventura County line.

The revamped 4th District would include heavily Latino communities, including South Gate, Huntington Park and Lynwood, that are now part of the 1st or 2nd districts.

Under this proposal, about 56% of voters in the 4th District would be Latino.

Solis’ 1st District would contain about 51% Latino voters, as well as 26% Asian voters with the addition of Hacienda Heights, Rowland Heights and Diamond Bar.

“For us, the value at the core of all of this is ensuring the most disenfranchised communities and their voices are heard through this process,” said Hector Sanchez, deputy director at Community Coalition, which helped organize People’s Bloc.

Intense jockeying underway as a state panel redraws California’s congressional seats

Some argue that over the last three decades, the First District has grown so heavily Latino that some Latino voters should be split off into another district to provide a better chance of electing a second Latino supervisor — a goal that would be accomplished by the map inspired by the People’s Bloc plan.

“Some of that population could be shared with another district and probably linked up with other significant concentrations of Latino populations in the county to draw two effective Latino districts,” said Arturo Vargas, chief executive at the NALEO Educational Fund, which facilitates Latino political participation.

The 2nd District has also become increasingly Latino. But advocates argue that drawing the lines to make it the second majority Latino district packs Black and Latino voters together, when they believe the 4th District is a better option for concentrating Latino voters.

L.A. County has never had an Asian supervisor, in part because Asian voters are concentrated in areas that are widely separated geographically.

Manjusha P. Kulkarni, executive director of the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council, said she wants to get past previous redistricting disputes that have pitted Asians and Latinos against each other.

“It’s one against the other fighting for the crumb, and we’re not willing to do that this time,” she said.

Rather than aiming for a district that favors the election of an Asian supervisor, Kulkarni’s group wants to see Asian communities, such as Little Tokyo and Chinatown, grouped together to increase their political clout.

For the supervisors, a redrawing of the lines could substantially alter their constituencies and potentially even land them in a different district.

The map concentrating many Black and Latino voters in the 2nd District would put Mitchell’s central L.A. home slightly outside of her current district and into Hahn’s 4th District.

That same map also places Kuehl, who lives in Santa Monica, in the 4th District — but she is not running for reelection.

Under the map grouping the coastal cities in the 3rd District, Hahn’s San Pedro residence would remain in the 4th. But much else about her job — and potentially her chances of reelection — would change.

“There are going to be millions of voters in L.A. County who wake up Dec. 16 being represented by a supervisor they didn’t vote for — and that is a real challenge,” Hahn said in a statement. “While I will miss working with and representing the Beach Cities if they are moved out of my district, I respect this independent redistricting commission and the work they are doing to draw districts that are as fair as possible.”

Some former supervisors defended the old method of redistricting, arguing that they had deep knowledge of their constituents and how to best group those with common interests.

Ridley-Thomas, who represented the 2nd District from 2008 to 2020, said state legislators took redistricting out of the supervisors’ hands because they resent the supervisors’ power.

He has pleaded not guilty to federal conspiracy, bribery and other charges stemming from actions he took while on the Board of Supervisors. In October, his colleagues on the L.A. City Council suspended him from his duties.

Former 4th District Supervisor Don Knabe, who served from 1996 to 2016, said he and his colleagues were held accountable by “communities of interest,” including those bound by ethnic, economic or other commonalities.

“Gerrymandering [was] probably still possible, but not without a lot of shouting and notice about what they’re trying to do,” he said.

The 14-member redistricting commission was selected from 741 applications, which were whittled down by the Los Angeles County Registrar to 60.

Eight commissioners were then randomly selected using a bingo cage in a process livestreamed on Facebook.

In public meetings, the eight commissioners chose six colleagues who they believed best reflected L.A. County’s geographic, political, racial and ethnic diversity.

The commission, which is all volunteer, is co-chaired by attorney Daniel M. Mayeda and Carolyn Williams, a certified life and executive coach. It has six women and eight men.

Seven commissioners are Democrats, three are Republicans and four are registered with neither party.

Six are Latino, four are white, two are Asian American-Pacific Islander and two are Black.

Members are barred from communicating with supervisors as well as supervisors’ families and employees.

Mayeda said the commissioners are aware of the complexities of the task before them.

Under federal and state law, each district must have roughly the same number of residents, and cities should stay in the same district where possible, as should neighborhoods and communities with common interests. Districts must also be contiguous and should be compact.

The federal Voting Rights Act requires that the lines be drawn so that racial and ethnic groups have a fair chance to elect a candidate of their choice.

“It’s all sort of a matrix or Rubik’s Cube — you change one thing and you kind of mess up the other,” Mayeda said. “That’s the challenge.”

The commission will meet again at least twice, then choose a final map by Dec. 15.

Many involved in the new process hope that it will break the cycle of powerful people perpetuating their own power.

“Redistricting is when leaders choose their voters. That’s been the old adage,” said José Del Río III, local redistricting advocate at the nonpartisan nonprofit California Common Cause. “That’s the one thing that we want to prevent.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.