Over 23 years, lessons in life and sobriety for a father and son on the Appalachian Trail

- Share via

It could have all ended in that cool rainstorm in southwest Virginia.

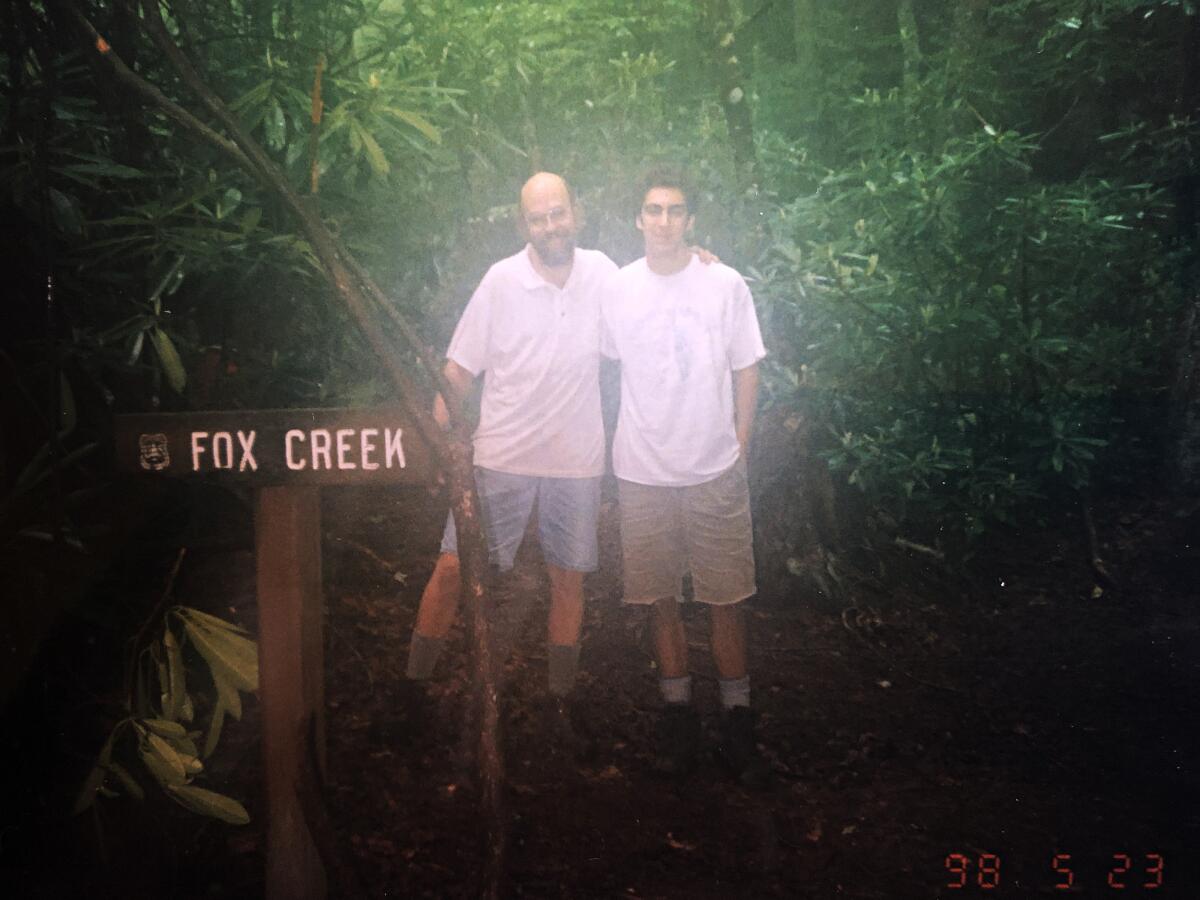

My dad, Sam Poston, had slipped in the mud and badly twisted his knee the first morning of our inaugural backpacking trip on the Appalachian Trail in May 1998.

Instead, he took some ibuprofen and wrapped the elastic waistband from a pair of underwear around his knee as a makeshift brace. He pushed through the pain and we eventually hiked 55 miles through a tunnel of flowering rhododendron and mountain laurel.

We feasted like kings the night we finished in Damascus, Va. We laughed about our blisters, heavy backpacks and my wet sleeping bag. We worked so hard to get there and we did it together. It was perfect. I was hooked.

At 18 and just out of high school, I felt truly free for the first time in my life.

Since then, we returned almost every year in our quest to walk 2,200 rugged miles that wind through 14 states from Georgia to Maine. This year we set off on the last leg of our journey, 150 miles through Maine ending with a punishing climb up Mt. Katahdin, the trail’s northern terminus.

In our 23 years on the AT, as it’s known, our lives were ever-changing, but the trail always offered us familiar peace from the outside world — a walking meditation through the quiet forest shared with each other and the countless hikers we met.

Ours was a journey only made possible by sobriety, as both Dad and I struggled with alcohol dependence for many years. Then there was his cancer.

I went from a bouncy teenager to a 41-year-old with a bad back. I converted to a new religion and got married. So much time has passed that I’m only seven years younger than Dad was on that rainy May morning in Virginia.

::

My dad had a three-decade run with mostly cheap beer, which ended in summer 1996, when driving drunk, he fell asleep at the wheel in southwest Ohio and drove his work van off the road and rolled it several times. He broke a few ribs and was pretty banged up.

I’ll never forget seeing his duck boots at the end of the hospital bed. He seemed embarrassed and really out of it.

He later told me that when he regained consciousness in the crumpled van, he had a moment of clarity. He said, “God, I can’t do this anymore.”

That was the last day he took a drink — Aug. 29, 1996.

Two years later, on our first trip, he was freshly sober and learning a new way of life. But I was just getting started.

I began drinking in high school, mostly on weekends with friends. It seemed the logical thing for a teenager to do in my sleepy hometown of Springfield, Ohio.

Within a few years, though, my grades suffered, especially after I discovered marijuana. Then I quit the basketball team and got into theater. But I was really into partying, which I perfected in college.

Eventually, our annual backpacking trips became the only times I was sober. The first few days on the AT I felt great with a clear mind, but after a week the siren song of alcohol was calling and I couldn’t wait to get off trail and alter my reality. Apparently I was pretty good at hiding it — Dad said he never suspected I had a problem.

I would anxiously anticipate any town stop where I could grab some beers with a meal. Sometimes, alcohol just appeared — a phenomenon known as “trail magic.”

Camping by a North Carolina river in 2003, we met an intoxicated Southern gentleman teetering side-saddle on a horse with an enticing offer: “Want a cold beer?” Of course I did. He then proceeded to offer me moonshine, which I took a swig of, then weed, which I declined because Dad was there.

We laughed about it later, but I felt self-conscious drinking in front of him, worried it might trigger a relapse.

In 2012, I moved to Los Angeles to take a position with The Times. Alcoholism is a progressive disease, and by fall 2014, I was in a pretty bad way — isolated, paranoid, depressed and struggling to maintain relationships. Daily responsibilities felt overwhelming and I came close to quitting my dream job and going “all-in” on the alcohol game.

Then I thought of my dad. His life of sobriety had shown me there was a way out. After some half-hearted attempts to quit, I went out with a whimper. I took my last drink — a few spoiled glasses of red wine in my dingy Los Feliz kitchen — on Nov. 23, 2014.

I was what they call a “high-bottom” drunk. I didn’t lose it all or end up in prison. Still, I felt lost and lousy for more than a year after I stopped. I eventually found a way to live without my lifelong best friend, alcohol, with the help of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Our experiences in sobriety have brought my dad and me closer, especially on the AT. Altogether, we have spent more than six months of our lives together on the trail, taking roughly 5 million steps each.

For years while I was battling my demons, I never never broached the subject, never revealed my truth. But sitting around the campfire these days, we don’t hold back. I’ve shared some of my darkest and most embarrassing moments and he’s done the same.

The AT has dominant party culture. Many hikers imbibe in town and toke on the trail, but we’ve camped with other sober hikers and even once took part in an impromptu A.A. meeting at a shelter near Lehigh Gap, Pa.

::

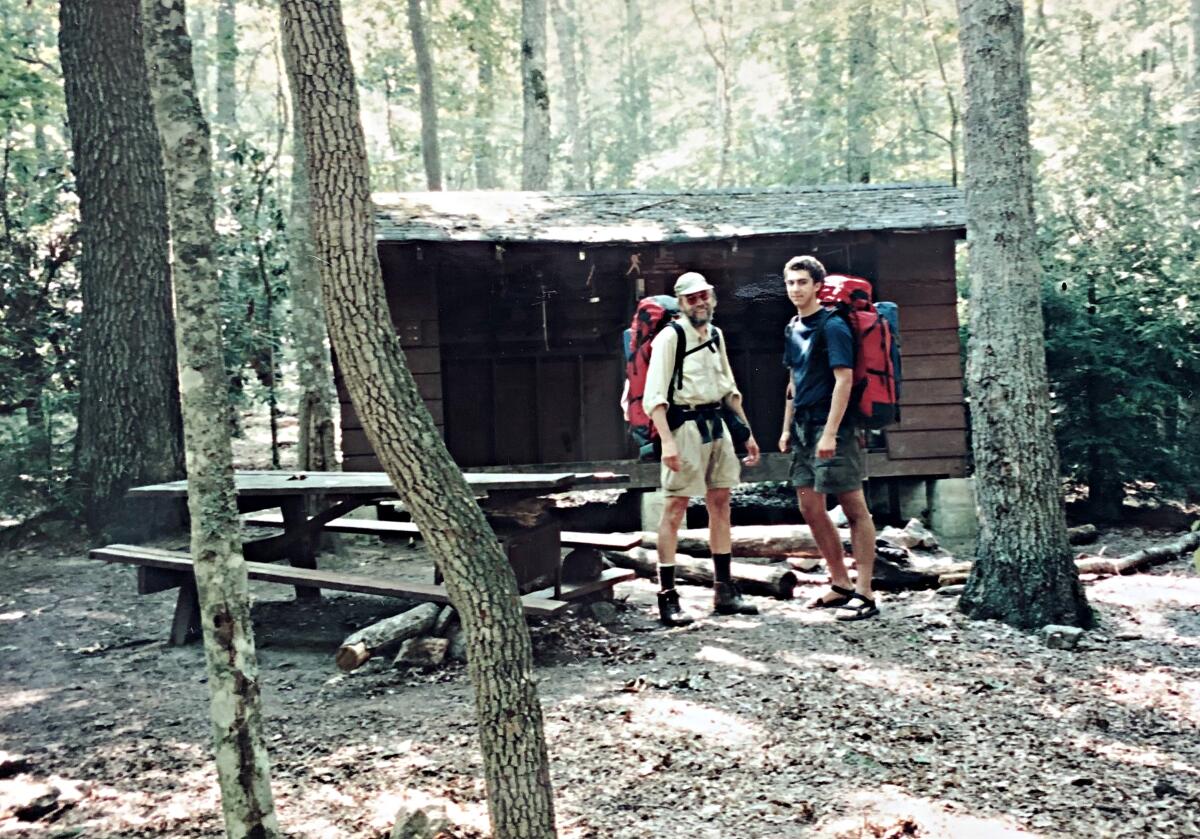

Dad had been a longtime smoker and was diagnosed with Stage 1 vocal cord cancer in 2008, just a month before we had planned to hike in southern Maine — widely considered the most difficult section of the trail.

His voice had grown hoarse for months, and it was hard for him to be heard in a crowded restaurant. After a year of worsening symptoms, doctors had found a cancerous growth on his vocal cords.

He asked my mother, Kathy Poston, if he should still go on the trip. She told him that it could be a welcomed diversion and might set an example for me on how to persevere in a time of adversity.

While the AT is shorter and less remote than the Pacific Crest and Continental Divide national scenic trails — the other legs of the “Triple Crown of Hiking”— it’s widely considered to be more rigorous step-for-step than the others. The AT pummels hikers with incredibly steep climbs and descents, and even flat sections require near-constant decision-making to navigate an endless gantlet of rocks and roots slippery from frequent rain.

Only about 25% of hikers who attempt the entire trail make it all the way, according to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy.

Indeed, my dad inspired me that summer with his grit. He was such a champ as we scrambled over tricky spots, like the Mahoosuc Arm that tested our every step in a full-on rock scramble.

I’ll never forget the day we finished in the pouring rain after a long descent into Gorham, N.H., and we just gave each other a knowing look that said: “I’m glad we survived that.”

Luckily, doctors had caught the cancer early and he was able to undergo localized radiation treatments. He’s been in remission for more than a decade and he quit smoking. As his lung capacity increased, he’s become a tough, old mountain goat who doesn’t need to take breaks on long climbs anymore.

::

My dad’s trail name is Festus, after the character Festus Haggen on the TV classic “Gunsmoke.” He used to go by Pyro for his fire-making prowess. For years, he has carried a 6-ounce foldable saw to cut down dead trees. He also packs a baggie of dried birch bark as a fire starter.

My parents hiked a 30-mile section of the AT in Tennessee in the mid-1970s, so my mom has an appreciation for the trail. Her honorary trail name is Mama Bear and she has long been our cheerleader, travel agent and weather forecaster. Each year we arrived home safe, she shared in the joy and absurdity of what we were attempting to do.

Alas, I am known as Skid Mark, an unfortunate nickname I got as an adolescent from Uncle Glen, whose completion of the trail in 1974 initially inspired us to hike.

Over the years, we’ve met a multitude of hikers with trail names like Dozer, Florida Man, Jaws, Natty Bird Dog, Water Queen and Wolfey Bizzerk. They represent a cross-section of society: teachers, nurses, former stockbrokers, veterans, college students, retirees and a lot of people just trying to figure out their next move in life.

I am inspired by every long-distance hiker I meet. The mental fortitude it takes to get up and put on wet socks and damp clothes and hike in the rain and muck for days on end can’t be overstated. The physical demands wreak havoc on the feet, ankles, knees, back and shoulders. Bug bites, bee stings and blisters occur with such frequency that you lose track.

We’ve met runners who covered 50 miles a day. We’ve met homeless people who call the trail their home. We’ve met barefoot hikers and naked hikers. There was a young man in Tennessee who slept underneath a shelter with the mice. Another guy in West Virginia offered some trail wisdom to explain his tiny backpack: “The more you know, the less you need, I reckon.”

For us, the trek was never about impressing strangers with feats of stamina. Still, at times we’ve gotten distracted by hikers doing longer miles and questioned our progress. But a simple trail mantra snaps us back to reality: “Hike your own hike.”

Festus and I even came up with our own slogan: “A lot of miles, a lot of smiles and a lot of high-fives.”

::

Walking along the trail in Massachusetts in 2019, I faced a tough conversation. But somehow the AT made it possible.

After several years of dating a beautiful woman named Shira Gordon, I had decided to convert to Judaism before we got married. She is the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor who helped raise her, and her religion is very important to her.

I attended a Protestant church as a teenager but drifted away while my parents stayed active at a Lutheran church in my hometown. I had talked to Mom about my decision to convert and she accepted it, but I was worried about Dad.

After a few days of hiking with butterflies in my stomach like I was about to give a speech before a large crowd, I finally worked up the courage to approach him as we walked along the sunny trail.

“I’ve been thinking about it,” I said, “and I’ve decided to convert.”

“It’s your life, I’m not going to stop you.”

I felt a tremendous weight lifted off my shoulders. It took some time, but he eventually came to accept my decision. Shira and I were married at the end of the year. For the first time in his life, my dad wore a yarmulke and we all danced the horah.

The remainder of the 2019 trip was mostly a delight — until the last quarter-mile. Festus slipped on a rock and fell into a deep stream and floated for a few seconds like an upside-down turtle. He was hiking by himself, and got distracted by a podcast on his phone.

He came out of the Vermont forest soaking wet on a clear day, which was hysterical at the time. Reflecting later, it spooked me. What if he had hit his head? He was nearly 69. I knew I needed to stay with him the following year.

::

Those plans fizzled with the pandemic, but this year, fully vaccinated, we prepared to complete the AT. Festus turned 71 in July, but I knew he had enough in the tank to finish. In mid-August we flew to Maine and were off.

The trail in Maine is mentally exhausting. It’s tough to get into a comfortable stride with all the wet tree roots, slate and granite. One novice southbound hiker asked, “Do the roots ever let up?” Another described the trail as “brutiful,” simultaneously brutal and beautiful.

We hiked the famed 100-Mile Wilderness, the most remote section of the trail. Toward the end of the trip, I was walking along one sunny afternoon and had a vision of my Uncle Glen hiking the same trail nearly 50 years earlier by himself.

I thought about the thousands of courageous hikers we met, the hundreds of shelters and tent sites where we slept cocooned in our sleeping bags, the cold streams we collected water from, the roaring fires we built to stay warm.

I reminisced about the restless hours in my dad’s Toyota truck listening to classic rock as we drove to the trail from Ohio, watching the scenery morph from soybean fields to foothills to green mountains.

More than anything, I thought about the tranquility of the trail, how it welcomed us each year, whether I was drinking or not. When I’m truly in the moment on the trail, I babble to myself. That afternoon, these words poured out: “Oh my sweet AT.”

The day we attempted Mt. Katahdin I was a little nervous for Festus. We faced a lot of rock scrambling on the 4,000-foot climb and his balance can be a little wobbly at times.

An incredibly kind Georgia man named Big Heart, a 65-year-old section-hiker we befriended on the trip, helped us. A retired software developer and business owner, he was finishing his 16-year journey that day, so it was just as meaningful for him.

On the way up, we met Walkie-Talkie, a 31-year-old physical therapist and powerlifter, who had ascended the mountain before. She and my dad struck up a conversation that kept the mood light even as we climbed up and over hundreds of boulders.

I led our small group, calling out the safest foot and hand positions while Walkie-Talkie brought up the rear, making sure the Boomers were safe. I told her later she was our guardian angel that day and she blushed and took no credit.

As we neared the top, clouds obscured the sun, the wind picked up and the temperature dropped. Even so, it felt like a dream — all these years of wandering finally coming to an end. The day before, Festus had celebrated 25 years of sobriety.

At the summit, my dad and I grabbed the Mt. Katahdin sign at the same time. I put my arm around his shoulder and we cried.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.