Dozens of L.A. County communities face growing peril from fire, heat, flooding

- Share via

The Crenshaw sidewalks sizzled on Wednesday as Ang Flore worked to sell face masks, plastic toys and electronic gadgets to people passing by. There were few takers beneath the blazing sun.

A native of West Africa and former resident of Las Vegas, Flore said she was used to heat, but that she moved to Los Angeles because she was initially drawn to its more temperate weather.

“But as the years go by, you feel the difference,” said Flore, 40. “Us outside — we notice it a lot.”

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

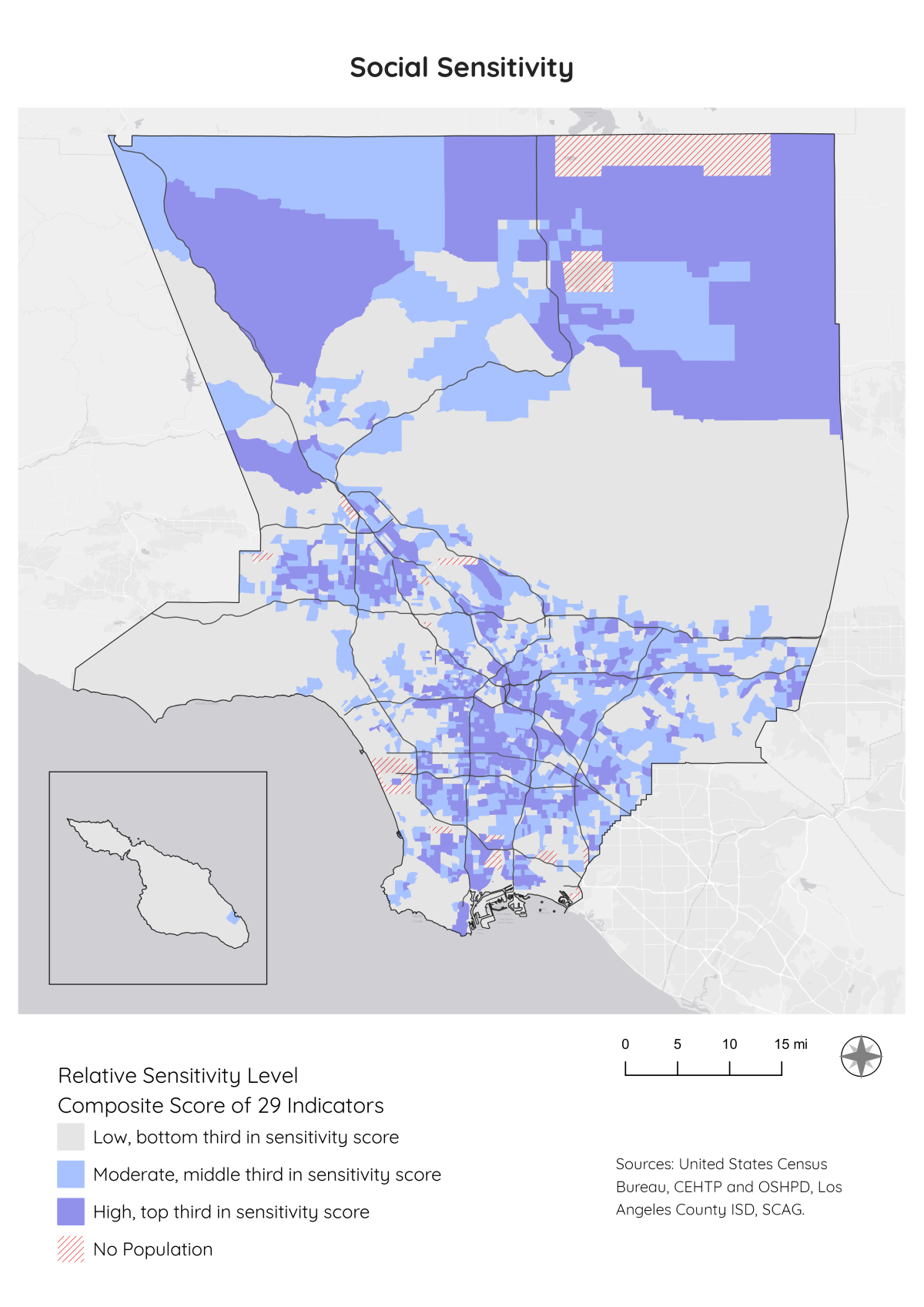

Crenshaw is one of at least 47 communities where the worsening impacts of climate change will be felt most acutely, according to a groundbreaking new L.A. County report, which outlines in stark detail how some of the Southland’s most vulnerable residents could bear the brunt of extreme heat, wildfires, drought and floods.

The Climate Vulnerability Assessment found that those communities face “dual dangers”: an increased exposure to climate hazards combined with factors that will make it harder to respond and recover from those events, such as age, health, income and infrastructure. Many of those communities are home to low-income people and people of color.

Residents of Crenshaw and Westlake, for example, are at risk for inland flooding and lack uniform Internet access for emergency information. Santa Clarita is highly vulnerable to worsening heat and wildfire, and is also home to an older population with limited transit options.

The findings lay bare how social and economic inequality — driven in large part by historic and ongoing racist policies and practices — leaves millions at a disadvantage as the climate crisis heats up. Some who worked on the report said it underscores the urgent need to take action.

“A document like this really says you’ve got to do more to mitigate, but you also have to help communities become more adapted to the changes that are coming,” said Los Angeles County’s chief sustainability officer Gary Gero, adding: “It doesn’t have to be this bad.”

Paved surfaces, tree cover, and home construction quality can make the difference between heat waves being an inconvenience or a threat to your life.

Among the communities facing multiple high-risk climate threats are East Los Angeles, South Gate and Bellflower; Long Beach and San Pedro; Santa Clarita; Reseda and Winnetka; Montebello; Westlake and Crenshaw; and parts of Antelope Valley, according to the report.

Many are home to Black and Latino people, with the report noting that Latino people represent 67% of the population in communities with high vulnerability to extreme heat, despite being less than 49% of the county’s population.

“I thought I was going to die this summer,” said James, a 36-year-old gas station worker in Crenshaw who declined to give his last name. “I live in an upstairs apartment and I got no sleep — it was so hot.”

)

Among the most visible and destructive of the worsening hazards is wildfire. The northern portion of L.A. County will face the most direct risks from wildfire, with the San Gabriel Mountains projected to see a 40% increase in wildfire burn area by 2050.

But wildfires affect more than just the people who live near them. Many underrepresented community members are often forgotten during wildfires, said Nancy Zuniga, program manager at Instituto de Educacion Popular del Sur de California, which represents day laborers and domestic workers and also contributed to the report.

“Not everyone gets impacted by climate in the same way,” Zuniga said. “Not everyone gets impacted by emergencies in the same way. That’s at the core of how we see a lot of these issues.”

Many workers after the 2018 Woolsey fire described feeling trapped in the burn zone — in part because the majority of evacuation communications were on Twitter and in English, Zuniga said. Some had to evacuate on foot or by public transportation, which often took hours and left them exposed to harmful wildfire smoke or encroaching flames.

One such worker said he was paid about $700 to protect a group of homes in Malibu with a hose, a job he accepted because he needed the money.

“When there are disasters — and most of them are climate change-related — all these issues, all this lack of infrastructure, lack of access, get heightened,” Zuniga said.

Although the Los Angeles area has become more diverse in the past 30 years, it is barely more integrated today than it was then, and it remains the sixth-most segregated metro region of 221 studied.

Also of concern is flooding — a hazard that is easy to forget amid L.A.’s extreme heat and droughts. The county’s coastal areas are increasingly susceptible to rising sea levels and erosion, while many inland areas are vulnerable to landslides, mudslides and flooding due to bouts of extreme precipitation, such as the recent record-breaking atmospheric river that dropped a deluge across the state.

About 720,000 people in L.A. County are in danger of being impacted by floods, according to the report. Among the communities of concern are Long Beach, Melrose, Sun Valley, Crenshaw, Westlake, Lynwood, Roosevelt and Country Club Park, as well as people who live along the L.A. River.

In Westlake’s MacArthur Park on Wednesday, Milko Vasconcelos, 49, said he has been aware of climate change since Al Gore’s 2006 documentary “An Inconvenient Truth,” but that he often feels powerless against it.

“It feels like ‘us versus them,’ but ‘them’ is a huge power,” he said.

Read all of our coverage about how California is neglecting the climate threat posed by extreme heat.

Yet many of the conditions that make Los Angeles so vulnerable to climate change are also what make it such a desirable place to live, said Jonathan Parfrey, executive director of the nonprofit advocacy group Climate Resolve, which contributed to the report. The mountains and forests are subject to wildfires, while the beaches and coastline bring the potential for more floods. The warm, sunny weather is the product of an arid Western climate that is also prone to drought.

Because of that unique topography, “you have to look at the impacts of climate change in Los Angeles almost neighborhood by neighborhood,” Parfrey said.

Essential workers will be critical as climate change worsens, he said. People who know how to fix the power grid or repair water pipes in the event of a catastrophe could help prevent “cascading impacts,” such as not having water to fight fire, or not having electricity to power hospitals or medical devices.

“Without those things — without electricity, without a workforce — you’re going to have a lot more damage to both the infrastructure of the city and to human beings,” he said.

Utilities have funds available to install air conditioning in low-income households, but for one California family, help did not come soon enough.

Many researchers said extreme heat was the most worrisome finding in the report, with countywide daily maximum temperatures projected to increase by an average of 5.4 degrees to a mid-century average of 98.6. The largest increases in frequency, severity and duration will occur in the Santa Clarita and San Fernando Valleys.

There are “significant policy gaps in protecting communities from extreme heat,” said Nurit Katz, chief sustainability officer at UCLA. One such gap is a lack of upper temperature limits for indoor workers; another is that landlords are required to provide heat but not air conditioning.

According to the report, the annual number of heat waves is expected to increase tenfold by mid-century.

And while drought could not be mapped at a census tract level, researchers noted that prolonged hot and dry periods are likely to persist throughout California. These dry spells could threaten the region’s water supply, which is heavily reliant on water imported from the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the Owens Valley and Colorado River.

Households reliant on the most vulnerable water systems face the possibility of cutbacks during droughts, and higher water rates.

In Glendale, for example, a household earning less than $25,000 per year would see the cost of their basic water needs increase from 1.8% of their income to 2.1% due to drought charges, according to one study cited in the report.

To water resiliency advocates at the U.N. climate conference, the Colorado River stands out as ‘the best example globally of how things can go badly.’

The county’s projections “are frightening but not inevitable,” the report states. There are some solutions, said Gero, the county’s chief sustainability officer. Eliminating oil drilling and continuing to invest in renewable energies are critical to reducing greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change.

Smaller changes, such as cooler roofs, more trees, improved infrastructure and increased access to community services, will also help. The state this year allocated $3.7 billion to climate resilience projects, Gero said, and about $500 million has been carved out for urban areas like Los Angeles.

But some solutions will also require reckoning with mistakes of the past.

“Disasters can happen over seconds, but they also can happen over decades,” Gero said, “and that’s what this report is meant to point out.”

In MacArthur Park, 23-year-old Bryson Nihipali said climate change is something he thinks about a lot, and that it concerns him that “people with the least amount of money are the ones who suffer most.”

“I guess that’s the way of the world,” Nihipali said. “Some people have, some people don’t have. It’s on ‘the haves’ though — the ball is in their court.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.