COVID-19 risks in kids are small, but vaccines can still save lives, experts say

- Share via

Although the chances of serious illness and death from COVID-19 are exceedingly slim for children, experts say there’s a very good reason for parents to get their kids vaccinated.

COVID-19 has become one of the leading causes of death in children nationwide.

There were 66 COVID-related deaths among children ages 5 to 11 in the yearlong period that ended Oct. 2, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, making COVID-19 the eighth-leading cause of death in that age group.

More recent CDC data show at least 94 COVID-19 deaths among 5- to 11-year-olds nationwide since the start of the pandemic. Among all U.S. children younger than 18, there have been 765 COVID-19 deaths.

Children 5 to 11 are making up a greater proportion of coronavirus cases nationally. They included 10.6% of all cases reported to the CDC for the week of Oct. 10, even though they comprise only 8.7% of the U.S. population, according to Dr. Fiona Havers, a medical officer in the CDC’s Division of Viral Diseases, who spoke this week at an advisory committee meeting of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

COVID-19 can be a leading cause of pediatric death even with the low chances of children dying of the disease because most of the time “children don’t die” at high rates for any reason, said Dr. Monica Gandhi, a UC San Francisco infectious-diseases expert. But during the Delta variant surge, in places with low rates of adult vaccination, “kids got a lot of cases, and there were more hospitalizations in children than we have ever seen before.”

Any child’s death is tragic, particularly one that can be prevented by vaccination, health experts say.

“It’s kind of like: What if you had a vaccine that was totally safe,” Gandhi said, and a child “would never get cancer?”

A panel of U.S. health advisors endorsed kid-size doses of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, moving the U.S. closer to vaccinating children ages 5 to 11.

Another reason to have children vaccinated, experts say, is to suppress the circulation of viruses among younger people so they don’t expose older people or those who have weakened immune systems. Anyone in those groups who gets a breakthrough infection despite being vaccinated is at greater risk for severe illness, hospitalization and death, data show.

In addition, children who contract COVID-19 are also at a small risk of developing multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C, which can trigger inflammation of the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, skin, eyes and gastrointestinal organs. There have been 660 cases of MIS-C in California, including six deaths, and more than 5,200 cases of MIS-C nationwide, including 46 deaths.

Preliminary data suggest that 8% to 9% of children admitted for MIS-C are diagnosed with myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart.

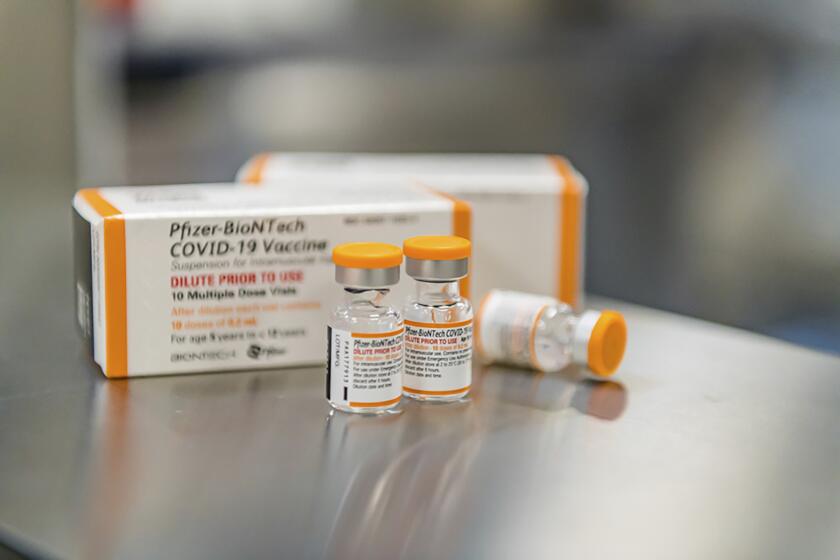

Some parents have voiced concern about the safety of the COVID-19 vaccines, given their relative newness. Only one vaccine in the U.S. — the Pfizer-BioNTech shot — is available for those under 18.

The Pfizer shot has been fully approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for those 16 and older and authorized for use on an emergency basis for children ages 12 to 15. It could be authorized for emergency use in children 5 to 11 next week.

Pfizer says its COVID-19 vaccine works for children ages 5 to 11.

Concern has arisen over the risk of myocarditis as a side effect of the Pfizer vaccine. But there has been promising, if limited, data as it relates to children 5 to 11.

A preliminary study showed no risk of myocarditis in a trial group of 5- to 11-year-olds, Gandhi said, although an initial study involved just 2,268 children, with 1,518 getting the vaccine and 750 receiving a placebo. It’s fair to point out that the sample size is not large enough to detect rare side effects, Gandhi said.

Each vaccine dose studied for children 5 to 11 contained 10 micrograms; older recipients get 30 micrograms per dose.

Male teenagers and younger adults have also been seen to have a higher risk of myocarditis after a Pfizer shot. According to the fact sheet distributed by the FDA, there is an observed increased risk of myocarditis, especially within a week following the second dose. The risk is higher among men younger than 40 than it is in women and older men. The observed risk is highest among boys ages 12 to 17.

Nonetheless, the overall risk of developing myocarditis in those groups remains small. And in a study of 63 patients diagnosed with post-vaccination myocarditis, 86% had resolved their symptoms during the study period.

“The hospital course is mild, with quick clinical recovery and excellent short-term outcomes,” according to the study’s authors, reported in the journal Pediatrics. More study is needed before long-term implications can be appraised.

When can parents expect their kids to be eligible for a COVID vaccine? Here’s the latest.

Anyone concerned about the rare risk of myocarditis can lengthen the time between doses of the Pfizer vaccine, Gandhi said. In her family’s case, she got her 13-year-old son his second dose seven weeks after the first, and she plans to give her 11-year-old son the vaccine as soon as it’s approved for his age group.

The official recommendation for the two-dose Pfizer vaccine is to get the second dose three weeks after the first; the CDC has said the second dose may be given up to six weeks after the first dose.

Gandhi said she thinks lengthening the time between the two doses dramatically decreases the risk of myocarditis, based on data from other countries.

She pointed out that the chance of myocarditis following a COVID-19 vaccine is nearly four times greater in Israel than in the Canadian province of Alberta. In Israel, only three weeks typically pass between the two Pfizer doses, as directed by the manufacturer. But in Canada, government officials directed a much longer gap between doses — generally one to four months, largely depending on supply.

Gandhi also cited data from health officials in British Columbia suggesting that the Pfizer vaccine works better if the length of time between doses is more than six weeks. Between late May and mid-September, studies there showed that vaccine effectiveness against infection was 90% or greater if the interval between the two doses was more than six weeks; it was 82% to 85% effective if the time between shots was three to six weeks.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.