Column: A returned Bruce’s Beach? Police reform? It was a good day for Black Californians

- Share via

Black people don’t get many good days in this country.

We’re disproportionately thrown in prison and killed by police. We’re disproportionately sick and disproportionately die, most recently from COVID-19. And, thanks to the stubborn tentacles of systemic racism, we’re disproportionately broke and unemployed.

But for Black Californians, at least, today — that is, Thursday, Sept. 30, 2021 — was a good day.

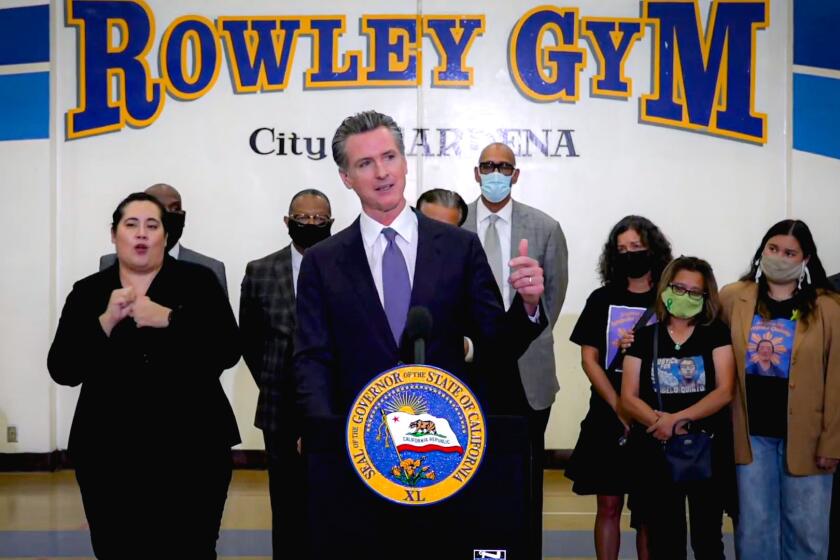

It was in the morning that Gov. Gavin Newsom stepped onto a podium at Rowley Gym in Gardena and explained why he was signing a package of bills that will, at last, force law enforcement agencies to hold their officers accountable for racial bias, misconduct and abuse.

“I want folks not to lose hope, that just because things aren’t happening in Washington, D.C., that we can’t move the needle here, not just in our state but in states all across this country,” he said.

Newsom, of course, was talking about the abject failure of Congress — well, of Republicans — to pass the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act.

The changes include raising the minimum age for officers to 21 and allowing badges to be taken away for excessive force, dishonesty and racial bias.

That was the package of federal bills that was offered up as the great hope for systemic change in American policing after Officer Derek Chauvin murdered Floyd with his knee on the streets of Minneapolis.

It was what Black people were supposed to get after the mass protests and racial reckoning that followed.

But that didn’t happen. Except in California.

Of the eight bills Newsom signed Thursday morning, one raises the minimum age for police officers from 18 to 21, another sets new rules for using rubber bullets and tear gas for crowd control, and yet another requires officers to intervene when they see a fellow officer using excessive force.

But perhaps most consequential for Black Californians, who continue to be overly and aggressively policed, a bill by Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena) allows the badges of problematic cops to be taken away permanently.

It “establishes a fair and balanced way to hold officers who break the public trust accountable for their actions and not simply move to a new department,” he said of his bill, which is now law.

Newsom added: “I hope this provides a little contrast to that anxiety and fear.”

It does.

The good day continued in Manhattan Beach.

It was in the afternoon that Newsom stepped up to a cluster of microphones, set up a block from where the waves were crashing into the sand under sunny skies. Then he explained why he was signing a bill to return the swath of grassy land before him to the descendants of a Black couple, Willa and Charles Bruce.

“As the governor of California, let me do what apparently Manhattan Beach is unwilling to do. I want to apologize,” he said. “I say that as a proud Californian, but also mindful that we always haven’t had a proud past.”

The Bruces had purchased the land along the Strand, between 26th and 27th streets, back in 1912 for $1,225. Together, they opened a lodge and dance hall, operating what quickly became a popular destination for Black families looking to enjoy a weekend at the beach, knowing they were banned from other stretches of the Pacific Coast.

Gov. Gavin Newsom authorizes returning the land known as Bruce’s Beach to the descendants of a Black couple that had been run out of Manhattan Beach.

The good times didn’t last, though. The Bruces were harassed by racists, including the Ku Klux Klan, for years. When that didn’t scare them away, officials with the city of Manhattan Beach condemned the neighborhood and seized the land in 1924.

Today, it’s known as Bruce’s Beach.

“The law was used to steal this property 100 years ago, and the law today will give it back,” said L.A. County Supervisor Janice Hahn, with fellow Supervisor Holly Mitchell by her side.

The Bruces’ story is the story of so many Black families. People who were forced off their land by racists and, with it, lost a chance at generational wealth.

This bill that Newsom signed also was written by Bradford, who serves as head of a reparations task force focused on coming up with ways to repair the harm that systemic racism has done to Black Californians.

“I hope we’ve shown today what leadership looks like on issues of reparations,” he told me. “What leadership looks like on the issues of criminal justice and police reform. And I hope we’ve set a fine example of what the rest of the states in the nation can do.”

As Newsom sat down at a table and picked up a pen, dozens of people — journalists, lawmakers, Manhattan Beach residents — gathered around for a closer look. A ripple of excitement seemed to shoot through the crowd.

Black women behind me shouted. “Amen!” “Yes, Lord!”

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Anthony Bruce, the great-great-grandson of Charles and Willa Bruce, dressed in a vest and dark button-down shirt, quietly edged closer to the governor. He smiled in anticipation and then relief with the swish of the pen.

“We’ll be sending the deed over to you soon,” Newsom whispered to him.

Kavon Ward, the founder of the grass-roots movement Justice for Bruce’s Beach who has led the charge to return Bruce’s Beach to the descendants of the original owners, looked skyward.

She extricated herself from the crowd. I watched her put a fist in the air, as if to echo the words she had said minutes before.

Ward had shouted into the microphones, unafraid of the backlash in a wealthy city where Black residents still make up less than 1% of the population and where racism is clearly alive and well. Heck, only one elected official from Manhattan Beach bothered to show up for the signing ceremony.

“Power to the people!” Ward had said. “Power to my people!”

She hadn’t heard about the bills that Newsom had signed Thursday morning. As I told her about all the ways that California was about to reform policing, her eyes widened. Memories of how Manhattan Beach police had made her feel over the last year, as she fought for reparations, for justice for Black people, were fresh in her mind, she told me.

Black people, we agreed, don’t get too many good days. This was one of them.

More to Read

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.