The number of babies infected with syphilis was already surging. Then came the pandemic

- Share via

The woman said she was racked with pain and disbelief on the hospital bed, her belly slick with ultrasound gel, when a hospital worker delivered the news: There was a baby inside her.

It was a boy. Six months along.

And his heart wasn’t beating.

For months, the 30-year-old woman had waved off her swelling belly and ankles. Pregnancy seemed impossible because she had struggled to conceive in the past.

Besides, she said, “you put all the bad thoughts on the back burner when you’re high.”

It wasn’t until days later, as she grieved her unexpected baby at home in Los Angeles County, that a nurse called to tell her what happened, she said. She calls it “the S,” an illness she is still embarrassed to name.

More and more babies in L.A. County have been infected with syphilis in the womb, which can lead to stillbirth, neurological problems, blindness, bone abnormalities and other complications. Nine years ago, only six cases were reported across L.A. County, according to a Department of Public Health report. Last year, that number reached 113.

The numbers were already surging before the arrival of COVID-19, but public health officials fear the pandemic exacerbated the problem, closing clinics that screen people for syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections and putting new efforts to battle the disease on ice.

The woman whose baby was stillborn, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to protect her privacy, said she went into labor in a hotel room in January. She had avoided getting any medical attention despite having painful sores.

At the time, she said, she feared that going to a clinic could lead to her being jailed for using meth. “You think, ‘I’m going to get in trouble because I’m high,’” she said.

The surge in congenital syphilis has been especially frustrating to experts because the illness can be thwarted if pregnant people are tested and treated in time. Other countries have been credited with stopping mother-to-child transmission of syphilis in recent years, including Thailand and Belarus.

Federal officials once thought the United States was on the verge of joining them. Instead, cases of congenital syphilis have skyrocketed nationally, from 334 cases in 2012 to more than 2,000 in 2020.

“There was no sustained investment over the number of years that we needed to really eliminate syphilis,” said Mario Pérez, director of the Division of HIV and STD Programs at the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

Experts have tied the broader rise in syphilis to a tangle of factors including methamphetamine use and sex without condoms. Men who have sex with men have been especially vulnerable, but the accelerating numbers among women and babies have spurred particular alarm for health officials because of the potentially devastating consequences.

Syphilis is curable in an infant if detected and treated in time, but if a mother also is HIV-positive, a syphilis infection can drive up the risk of transmitting HIV to the baby by breaking down the natural barrier of the placenta, said Dr. Mikhaela Cielo, a pediatric infectious-disease doctor at L.A. County-USC Medical Center.

At least eight people died while they were living at the Airtel Plaza Hotel in Van Nuys, where hundreds of homeless people have been housed through Project Roomkey.

The illness has behaved as a kind of grim prism, refracting societal problems such as addiction and homelessness. In L.A. County, up to two-thirds of mothers who passed syphilis to their babies said they had been using drugs while they were pregnant, according to Department of Public Health studies of cases between 2016 and 2018.

Between 10% and 20% were unhoused. Forty percent never got prenatal care. And almost 30% had a history of arrest or incarceration. In L.A. County jails, eight cases of syphilis had been confirmed among 170 pregnant patients seen as of late August, said Dr. Noah Nattell, who oversees women’s health for the county‘s Correctional Health Services agency.

Syphilis is hardly limited to the jails, but “all of the systems that are in place that lead somebody to be incarcerated,” he said, “are also the ones that lead people to avoid or to be excluded from the medical system.”

The disease also reflects racial inequality: The vast majority of syphilis cases reported among L.A. County women of reproductive age have affected Latina and Black women, according to county statistics.

The woman who lost her baby said she started using meth at an overwhelming point in her life, facing the demands of a stressful job, school and a relationship that had grown strained after her earlier struggle to get pregnant.

At the time, the drug felt like “a ticket to freedom.” She quit her unrewarding job. Her boyfriend moved out. Meth made her feel brave, “like I could take a deep breath finally.”

She started seeing a man who told her he didn’t need to use a condom with her, a decision she now sees as naive. After they broke up, she got into a relationship with a friend who would become the father of her baby.

When the waves of pain began to roll over her in a hotel room where she was spending time with her boyfriend, another man and his girlfriend, the girlfriend quickly realized she was in labor and urged them to call 911, she said. But the men bristled at the idea, she recalled, because there were drugs there and they didn’t want attention from the police.

Jennifer Wagman, an associate professor of community health sciences at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, said the rebounding numbers of congenital syphilis across the country are a sign of missed opportunities to stop the disease. Researchers have found that nationally, not all pregnant people are screened for syphilis despite the urgings by health officials.

Even when they are diagnosed, nearly a third of pregnant women with syphilis did not get the care they needed, according to an analysis by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Wagman said many reasons are tied to other problems in their lives: Some are uninsured. Some may have gotten tested but never got results or treatment because they have no regular address or phone number.

And some fear that if they see a doctor and are found to be using drugs, they could be forced to give up their child. The L.A. County report found that between 2016 and 2018, at least 30% of babies with congenital syphilis were put into custody of the Department of Children and Family Services.

There are signs that deaths connected to fentanyl, a powerful painkiller tied to a string of fatal overdoses in Northern California, are on the rise in the Los Angeles area, law enforcement and health officials said this week.

County officials said doctors may report concerns about child safety to the DCFS, but it is “only in the most extreme cases” that an infant would be removed, following an assessment that occurs after birth and not during prenatal care.

The L.A. County woman had also feared, after her baby was stillborn, that she could be criminally charged because meth was in her pregnant body — something that has led to charges for other women in California. At one point, the mortuary told her it had to put the cremation on hold because “the state got involved,” but no charges followed, she said.

Some experts see the resurging illness as a symptom of shortchanging sexual health. Jeffrey Klausner, a clinical professor of population and public health sciences at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, said federal funding fell off roughly 15 years ago, followed by cutbacks for public health agencies due to the ensuing recession.

In a county as vast as Los Angeles, he argued, there needs to be a proactive strategy to combat sexually transmitted diseases that reaches into affected communities. Instead, “everything has been very piecemeal, reactive and disjointed.”

The pandemic hasn’t helped. A state survey found that in the majority of health jurisdictions that responded, more than half the workforce had been reassigned to COVID-19 duties as of last September.

Reported cases of syphilis have fallen across California, but officials caution that could be due to less testing. Many of the clinics where the L.A. County Department of Public Health provides STD screening, diagnosis and treatment were temporarily closed amid the pandemic.

Plans to launch a new team focused on “rapid response” to syphilis cases — including offering testing to people in homeless encampments — were derailed. Nurses who ordinarily manage cases of women diagnosed with syphilis were pulled into coronavirus duties, which meant that others had to take on the task, managing 30 to 40 cases each on top of their other responsibilities, said Dr. Sonali Kulkarni, medical director of the county division of HIV and STD programs.

In August, the Los Angeles County Commission on HIV warned that “an already understaffed and under-resourced STD response was made worse by the redeployment of nearly all staff to COVID-19 work.” The bulk of county and community programs were “severely reduced in capacity or entirely put on hold.”

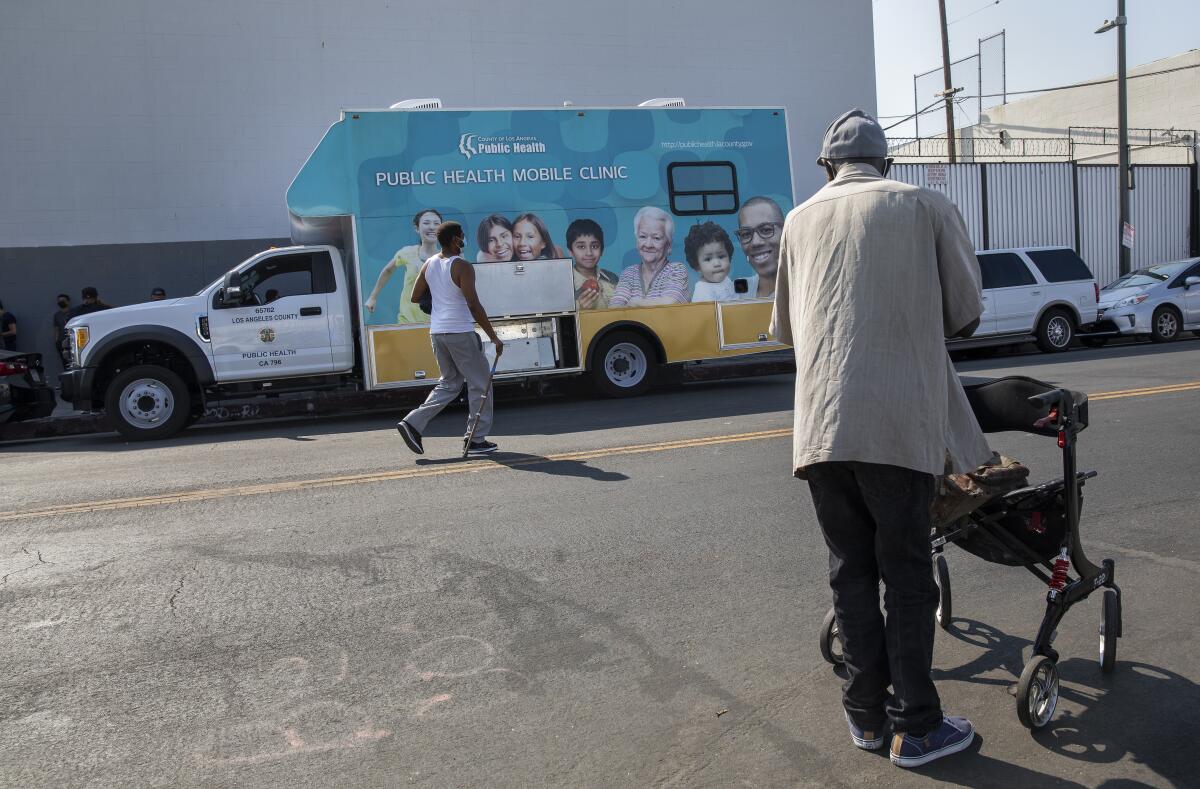

A rare exception is a mobile clinic on skid row, launched during the pandemic by Los Angeles Christian Health Centers, the People Concern and the county public health department, to test people for sexually transmitted infections.

Because its rapid test detects any syphilis exposure, including previous infections, more blood must be drawn to check for current infection. Getting those results can take days, which can mean tracking down patients on the street. The skid row effort also hands out hot meals, hygiene kits, naloxone spray to reverse overdoses and other necessities.

To reach people who are marginalized, “you have to be out here looking for them, making them feel safe,” said Ciara DeVozza, director of the C3 homeless outreach team on skid row for the People Concern. “That’s not how the medical system is designed.”

When her baby was cremated, the L.A. County woman asked to put his ashes in an urn decorated with an angel enveloping an infant in its wings.

“I always wanted a baby,” she said. “I always asked God for this and now I received this gift — and I have to decide how to put this gift to rest.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.