Recall election nears, but California’s widening, ugly political divide here to stay

- Share via

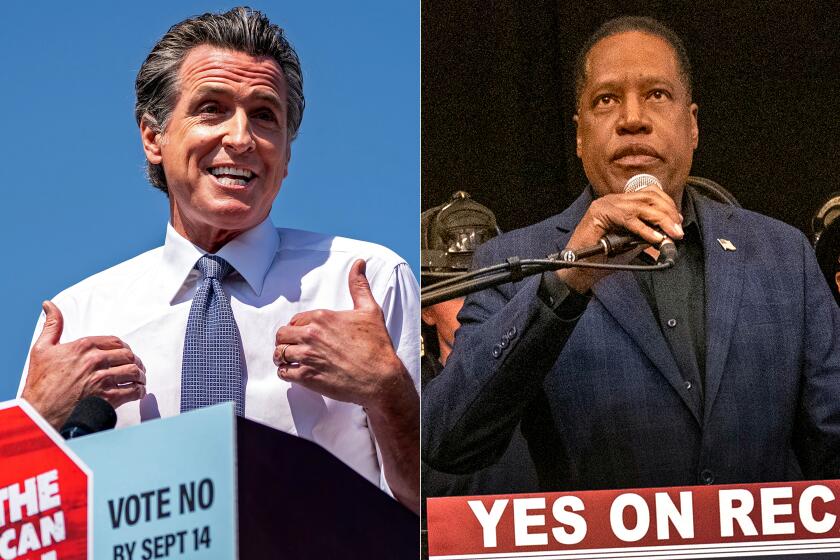

As the California recall winds down to its final hours, a central question has emerged that will probably dog gubernatorial hopefuls and voters into the upcoming 2022 election.

How much more of this can we take?

Though the current referendum on Gov. Gavin Newsom will wrap up on Tuesday — with recent polls strongly suggesting that he will prevail — the regular election is only a year off. Like wildfires, campaigning is no longer confined to a season.

Election efforts will probably keep rolling forward, making the recall one more chapter in a continuing storyline of identity politics that has captivated some, bored others and, for many, become an endurance test of civic engagement.

If Newsom loses on Tuesday, that upset could reshuffle the Democratic deck. If he retains office, the same slate of candidates is predicted to run again in 2022, though most, including Republican front-runner Larry Elder, have declined to state their intent until votes are counted.

“They might let everybody have a Christmas holiday, and then [we’re] back at it,” warned Edward Ring, co-founder of the conservative nonprofit California Policy Center.

Whether Newsom keeps his office or not, voters will be asked in June to choose their top two picks for governor in the primary, along with wading through a full slate of state and local offices and ballot measures that will probably include proposals on crucial issues such as criminal justice and water use.

Candidates wishing to collect signatures rather than pay a fee to be included on the next gubernatorial ballot can start gathering that support this December, and petitions collecting signatures on propositions will soon appear outside grocery stores and coffee shops.

How much interest voters will muster to stay engaged remains to be seen, but the top contenders in Tuesday’s gubernatorial recall showed few signs of fatigue going into their final weekend.

Dressed in a dark suit and maroon tie, Elder joined in a solemn ritual Saturday morning on a tree-lined street outside firefighter Scott Townley’s Fullerton home: Reading aloud the names of the nearly 3,000 people who perished 20 years ago Saturday in the Sept. 11 attacks.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom was a rising star in Democrat politics. How did he come to face a recall?

By lunch, the tie was gone, his sleeves were rolled up and he was eating inside a booth at the Texas Pit Bar-B-Que in Lake Forest, where he dined with formerly homeless veterans.

In Sacramento, Newsom began the day by laying a wreath in remembrance of 9/11 at the Wall of Heroes at the National Guard headquarters, which honors California National Guard soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan over the past two decades.

Then he headed to Oakland, where about 100 union members from the Service Employees International Union, representing long-term healthcare workers, were fired up in favor of keeping a governor who has long been an ally. He didn’t hesitate with his message that Elder is “consistently to the right of Donald Trump.”

For Newsom, he can only hope Elder chooses to campaign again.

“The people running to succeed Gov. Newsom are ridiculous,” former Gov. Jerry Brown said during a Friday night television appearance. “The recall, I think, paradoxically is going to strengthen Gov. Newsom and what he is trying to do.”

A fractured economy in the Golden State has driven income inequality for decades, and the recall offers no solutions.

Jack Pitney, a professor of American politics at Claremont McKenna College, said a recall victory over Elder would be “almost a perfect result for Newsom in 2022.”

Pitney said the emergence of the far-right Elder, a standard bearer for former President Trump who often makes bombastic statements, reminds him of a quote by 19th century German Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck: “There is a providence that protects idiots, drunkards, children and the United States of America.”

“That special providence is now protecting Gavin Newsom, too,” Pitney said.

How much divine protection Newsom garners ultimately comes down to how many votes he gets, said Dan Schnur, who teaches political communications at UC Berkeley and USC. A big win might make him bulletproof to criticism, but “if he gets [through] the recall narrowly, then he still sustains some political damage. He’s not dead, he’s wounded,” he said.

Mike Madrid, a Republican political consultant and co-founder of the Lincoln Project, which tried to rouse Republican opposition to Trump, said he believed the recall “may have been much ado about nothing” when it comes to parsing the power and fate of Golden State conservatives.

He doubts Elder or another candidate will pull off an upset, much less a future win. Madrid pointed out that Democrats in California have long outnumbered Republicans — who make up only 24% of registered voters — and Republicans have routinely lost statewide elections with margins that match that divide, showing that few voters cross party lines.

A close look at Larry Elder, the top challenger in the California recall election: his life, his beliefs and his sudden political rise.

While unseating Newsom would be cataclysmic, the results of the second question on who voters would choose as a replacement may be more relevant to understanding the future of the Republican Party in the state, Schnur said.

A single-digit showing for a more moderate candidate such as Kevin Faulconer would signal a pullback from Trumpism. By contrast, the predicted dominance of Elder would indicate California conservatives remain firmly in Trump’s gravitational pull, edging the party to an extreme that is riddled with conspiracy and mistrust of government. Recently, Trump said that the recall election was probably “rigged,” continuing to spread false allegations of widespread voter fraud.

Madrid said that a Newsom win would reinforce the diminishing relevance of Republicans in the state as that far-right flank becomes the party’s core, and could spark more recall attempts.

“As the Republican base shrinks, it is becoming more monolithic and extreme and excitable,” Madrid said. “It is choosing to regress and isolate in this bubble. When it starts to do that, it is going to become easier to qualify recalls but harder to get them to pass.”

That condensed anger was on full display last week at a rally at the state Capitol against vaccination mandates, though no such proposal was being considered by the Legislature.

More than 1,000 people gathered to protest, including a contingent of Alameda County firefighters, and a smattering of nurses and medical professionals who cheered while a speaker erroneously said that vaccinated people who contract breakthrough infections are five to six times more likely to die from COVID-19 than the unvaccinated.

One vendor was selling T-shirts with the image of state Sen. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), a proponent of vaccination mandates, his face stamped with “Liar” in blood red ink.

“I really believe that the silent majority is huge and I think that the polls are incorrect because a lot of people are waiting to the last minute because a lot of people want to vote in person,” said Linda Rich, a recall volunteer at the event who is convinced Newsom will lose Tuesday because of independent and crossover voters. “My No. 1 question to Democrats is why do you like Gavin Newsom?”

Rich said when she asks that question, she doesn’t often get a clear answer. But when she does, “99.9% of the time it is COVID related.”

That, Madrid said, might be the biggest takeaway of the recall: Voters don’t want their politicians to back down, especially when it comes to ending the pandemic.

“You are seeing that with Biden too now,” Madrid said. “Enough of the belligerence, enough of the immaturity … that might be one of the lessons to take from this, is not be be cowed by a vocal minority.”

California’s recall election ends on Sept 14, 2021. Here’s how to keep up with the latest coverage from the L.A. Times

Experts and voters on both sides of the political spectrum also say that the recall should be a wakeup for all elected leaders that Californians want less finger pointing and more of the unglamorous work of governance. A general indifference to Newsom’s fate among voters over the summer underscored that fact, bringing an uncertainty to the recall for weeks until fear that a far-right Republican might take charge became its own motivator.

Still, one of the few areas where Republicans and Democrats can find any agreement is that they are tired of the identity politics that both sides used to frame the recall race, and share a frustrating feeling that real issues are being ignored.

“There is genuine sense in California that a lot of things can be governed more responsibly,” Ring said. “I don’t think it’s partisan and I don’t think it’s restricted to any particular type of voter. I don’t think you can stereotype the voters who are feeling alienated and frustrated by the policies coming out of Sacramento.”

Schnur said he doubts that long-used and successful strategies are likely to fade anytime soon, especially in another race between Newsom and Elder, but he is optimistic that voters may get a longer break than Ring predicts.

“Even if a defeated candidate were to announce for next year on Wednesday morning, the campaign is not going to attract a great deal of public or media attention,” he said. “As a voter, you have more things on your plate to pay attention to this fall.”

Wick reported from Fullerton, McGreevy and Chabria from Sacramento.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.