Caldor fire smoke and ash are clouding Lake Tahoe’s famously clear water

- Share via

SOUTH LAKE TAHOE, Calif. — The Caldor fire has triggered mass evacuations in two states, torched hundreds of homes, made the air hazardous to breathe and spurred President Biden to issue an emergency declaration.

But the erratic wildfire is also causing another problem for Lake Tahoe: Smoke and ash particles are entering the lake and clouding its world-famous crystal blue waters.

Burning for nearly three weeks now, the fire has scorched more than 210,000 acres and blanketed the region in a haze of smoke.

Readings in recent days show the lake’s clarity — which is tracked by lowering a white disk below the surface and measuring the depth at which it disappears from view — has dropped to below normal for this time of year.

“We would expect to see something like 65 feet and we’re seeing something more between 50 and 55 feet,” said Geoff Schladow, director of the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center.

By Thursday, the heavy winds that had driven flames to the outskirts of South Lake Tahoe and the Nevada border earlier in the week had begun to subside, giving fire crews the opportunity to expand containment of the blaze. It also fueled a cautious optimism among some that the resort city had avoided devastation.

Scientists are trying to figure out whether the clouding of Tahoe’s waters is a temporary impairment that will go away after the smoke clears and ash stops falling, or something that could bring lasting damage to one of the lake’s most treasured attributes.

Researchers and environmental advocates worry that the Caldor fire — already one of the largest in California history — is an example of how the bigger, more intense wildfires we are experiencing due to climate change are emerging as a new threat to the movement to “Keep Tahoe Blue.” It’s a slogan that adorns countless vehicle bumper stickers and a mantra that has guided a decades-long effort and billions in public and private spending to reverse the degradation of Tahoe’s sparkling azure waters.

Thousands rushed to leave South Lake Tahoe as the resort city came under an evacuation order due to the Caldor fire.

“It’s looking like there’s going to be megafires with smoke affecting the lake more frequently: We’re talking two years in a row, and 60 to 90 days of unhealthy air quality and that’s depositing in the lake,” said Jesse Patterson, chief strategy officer for the League to Save Lake Tahoe. The environmental organization is helping fund a recent flurry of research into the smoke’s impact on water quality. “We need to understand what’s going on. Is Tahoe at risk of losing what attracted us all to it?”

The fires are degrading Lake Tahoe’s clarity in multiple ways.

Under normal conditions, sunlight at the high-elevation lake is so intense that algae grow only deep under the water, but the thick smoke has changed that, making conditions more favorable for algae growth closer to the surface. Smoke and ash particles that enter the lake get pushed around by waves and currents and make the water murkier. Those tiny particles also contain nutrients that stimulate the growth of algae, further diminishing the lake’s clarity.

Brant Allen, field lab director for the Tahoe Environmental Research Center, was one of the few people on the lake’s eerily empty, smoke-shrouded waters Wednesday. Standing aboard the 37-foot research vessel the John LeConte, Allen was taking measurements all the way down to the bottom of the 1,645-foot-deep lake.

“The clarity loss we’re measuring right now is fire-related,” Allen said.

Scientists are using research boats, buoys, underwater robots and other instruments to collect data on water clarity, temperature, concentrations of algae and tiny smoke and ash particles and other metrics that will help them understand the extent of the impacts, and how long they could persist.

An initial look at water samples taken by an autonomous underwater vehicle called a glider — which is currently surveying the upper 450 feet of lake water — suggest there has been a dramatic jump in particle concentrations, said UC Davis associate professor Alexander Forrest.

“Fine particles are affecting clarity, and are effectively creating a haze in the water that can last much longer than the smoke in the air,” Forrest said. “These particles, when in the water, can last on a time scale of weeks or months.”

He and other scientists are trying to understand the long-term implications of that change on the clarity of the lake, and the health of its ecosystem. They will be monitoring the lake to see how it fares in the months to come.

Tahoe is among the deepest lakes in the world and one of California and Nevada’s most prized natural wonders. Its waters, marinas, beaches, ski resorts, forests and casinos draw some 15 million visitors a year.

As the Earth warms and the drought deepens, a network of biologists and conservationists are racing to rescue California’s most threatened species.

Tahoe’s clarity was declining by about a foot each year from the 1960s through the 1990s, driven largely by development-caused storm runoff into the lake. But that trend was halted and has stabilized over the last 20 years, when billions of dollars were spent on projects to clean up the watershed and restore meadows and streams. Building restrictions and other measures have also helped to reduce the flow of sediment, nutrients and other pollutants into its waters.

“We’ve arrested the decline,” said Patterson, of the League to Save Lake Tahoe, or Keep Tahoe Blue. “The clarity has some good years and bad years, but what we’re seeing in the last five years is that climate change has changed the entire playing field. It’s like you’re playing a different sport because the variability is so great.”

It was an otherworldly scene at Lake Tahoe on Tuesday afternoon as fierce winds picked up and smoke brought on an early evening. The lake’s waters turned choppy as hundreds of empty boats bobbed listlessly. A few intrepid seagulls coasted in the gusts. On beaches usually crowded in the last days of summer before families return to school, there was only ash. Ash on picnic tables, ash blowing across the sand, and ash mixing with the turbulent waters before sinking into the lake’s depths.

Even when the ash stops floating through the air, additional threats to water quality could emerge later, when rain falls or snowpack melts in the spring. Erosion in burn areas could send more runoff into the lake and further degrade water quality.

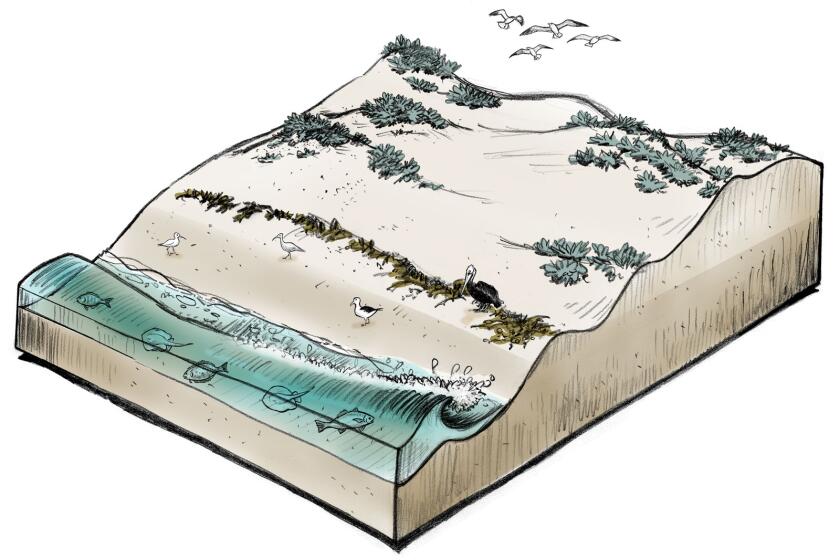

As sea levels rise, researchers are trying to bring back beach dunes and help buy communities a bit more time — before the ocean pushes inland and reclaims the land.

That’s exactly what worries Arthur Talsma, a wildlife biologist from Idaho who runs a potable water service for fire camps. He was on his way to the incident command center for the Caldor fire Tuesday night, and stopped at a picnic bench overlooking the lake, where he was surrounded by hungry squirrels and ducks looking for handouts in the evacuated town.

The ash floating through the air, he said, was of less concern to him than the runoff that could be unleashed over the next year, especially if heavy rains were to flush material from the burned areas into the lake.

“It’s going to change things,” he said. “And it can really change an awful lot if it’s in the watershed.”

Lake Tahoe’s water quality has suffered from fires before. Algae growth was affected by the 3,100-acre Angora fire in 2007 that burned in the Tahoe Basin and sent a lot of ash into the lake. But water clarity bounced back to normal about a month later.

This time however, scientists are concerned that the massive size of the Caldor fire and its proximity to Lake Tahoe could make for a bigger threat.

“There’s just way more material coming in this time, and it’s not over yet,” Schladow said. “So I’m expecting there to be a longer-lasting change from this fire compared to the Angora fire.”

Experts have historically been most concerned about fires affecting water quality through the erosion of watersheds. But this event raises concerns about smoke and ash becoming their own growing threat to the health of Lake Tahoe and other water bodies across the West — one that could begin undermining watershed protection and restoration efforts.

“The core issue,” Schladow said, “is whether these sorts of conditions are going to persist year in, year out.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.