- Share via

The accusations are ugly and public. The differences, textbook irreconcilable.

The two cities that make up the Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District want a divorce — and the points of contention are similar to those that plague most messy breakups. Money. Power. Fairness. And most volatile of all: what is in the best interests of the children.

These sun-kissed cities don’t share a boundary, or much of anything else, but for nearly 70 years they have been joined by their school system. For more than half that time, Malibu has been trying to leave.

“It has come to the point where everybody feels it is best to be separate, because there is just so much history,” said Santa Monica-Malibu Supt. Ben Drati. “The marriage is not working well. We just need to be able to divide the funding so no one’s harmed. … But what [Malibu] is proposing right now, it’s unconscionable.”

Malibu’s latest secession plan heads to a key public hearing in mid-September. If it is approved, the city would use its own property taxes to pay for its schools, would share some of those riches with Santa Monica for a decade and then would cut off its former partner.

Malibu wants control over how money is spent on education programs and teachers and over what courses Malibu high school students are offered. And it wants the ability to create a safety plan that accounts for the community’s particular disasters of fire, mudslide and flood.

Officials with the unified school district, who support secession but oppose Malibu’s current offer, warn that the proposal would leave a standalone Santa Monica district in the financial lurch and prompt deep cutbacks to programs for its diverse student body.

And what does Malibu say about the district’s objections to its plan for divvying up community property?

“Let’s stop pretending that this is about what’s fair,” said Christine Wood, Malibu deputy city attorney. “Santa Monica just wants the status quo — and that’s to keep Malibu in its grips.”

::

This is what life in Malibu schools is like.

According to City Councilman Mikke Pierson, students in his town are being left behind those in Santa Monica in terms of academics, facilities, activities and services. The fight, in part, is over whether it’s fair to have 17 Advanced Placement classes instead of 20.

“The only category we are ahead is in the amount of property taxes we disproportionately pay to SMMUSD to enhance programs that are mostly in Santa Monica,” Pierson said during a spring hearing on the breakup. Members of the “Santa Monica-centric” school board “clearly don’t understand the unique challenges we face as a rural community.”

What exactly does “rural” mean in Malibu?

To Councilwoman Karen Farrer, it means the town will never have a Trader Joe’s — “we don’t have enough people.” And there’s no “real car wash,” she said. (The hand-wash place doesn’t count.)

Malibu — a city where the median household income is twice that of Los Angeles County: $150,747 versus $75,235 — tends to invoke the language of social justice and educational equity when talking about the split.

The wrangling over dividing up plenty is happening at a time when other school districts are struggling just to get enough; when the Los Angeles Unified School District can’t hire teachers and counselors and librarians and nurses and mental health specialists to fill thousands of vacancies, and children have just returned to school confronting deep learning losses.

Yet Malibu perseveres in what residents see as a righteous campaign on behalf of its children. Proponents of secession argue that Malibu accounts for less than 15% of the students in the district, but the city’s property taxes make up 30% to 35% of SMMUSD revenue. They note that only two foreign languages (Spanish and French) are taught at Malibu High, while five (Spanish, French, Mandarin, Japanese and Latin) are taught at Santa Monica High, and that there’s a dual-immersion language program in Santa Monica, where students are taught in Spanish and English, but no such thing in Malibu.

District officials say schools with large enrollments have more money available for a wider range of programs. Santa Monica High, for example, had 2,816 students in the 2019-20 school year, about twice the population of Malibu’s four schools combined. Malibu High had 528.

Despite Malibu’s complaints, schools in both cities top the charts in student achievement. Santa Monica High and Malibu High both had graduation rates of 95.3% in the 2019-20 school year, nearly 10 points higher than the statewide rate.

Still, Wood said, “I don’t know why there would be a feeling that, ‘Well, there’s fewer students, so then we can cut back foreign languages to two versus five, or we don’t have to provide project-based learning.’ Why would Malibu students need to suffer those kind of inequities?”

And that, Pierson chimed in, “drives students to other places.”

“If you’re going to say how horrible the district is, you can’t say how shocked you are when people leave.”

— Jon Kean, school board President

Which raises yet another issue: Malibu schools have been losing students at a dramatic rate.

Between the 2014-15 and 2019-20 school years, the combined student population of the city’s two elementary schools, one middle school and one high school dropped 25%, from 1,871 to 1,406.

Malibu officials cite the Woolsey fire, which destroyed hundreds of homes in the area. They also blame school quality for driving students to private schools or other districts.

Not so fast, says Jon Kean, president of the school board — census data and housing stock tell a different story. The population of Malibu is getting older. From 2010 to 2019, the school-age population dropped 37%. The number of children younger than 5 — a school district’s future — dropped 49%.

Perhaps a third of Malibu’s housing stock is second homes for the rich and famous; more than three-quarters of Santa Monica residents are renters.

And then there are the intangibles. As Kean said: “If you’re going to say how horrible the district is, you can’t say how shocked you are when people leave.”

::

Malibu officials wonder why they should pony up so much money for what they view as an inferior education. It’s a matter of equity and local control, they say. They want Malibu property taxes to go to Malibu children.

But the complicated calculus of educational funding in California doesn’t work that way. Malibu, district officials say, can’t just take its money and run.

The state determines how much money school districts need through a mechanism called the Local Control Funding Formula. For the vast majority of districts, property tax allocations aren’t enough to reach that threshold, so the state provides the balance.

Then there are so-called basic aid districts — usually wealthy ones with expensive homes. Basic aid districts bring in enough revenue through property taxes that they exceed what they would receive through state funding formulas. This generally means that California doesn’t have to kick in additional money, and the district gets to keep any excess property taxes.

Los Angeles County has two basic aid districts: Beverly Hills and Santa Monica-Malibu.

If the divorce becomes final, the proposed Malibu Unified School District would retain basic aid status. But Santa Monica’s future status is unclear. Malibu has agreed to kick back money to the resulting Santa Monica Unified School District for 10 years to offset revenue loss. It’s for the 11th year that the two sides can’t agree on how to assess the financial impact.

If Malibu’s funding plan were enacted, SMMUSD officials said, it would strip programs and services from the district’s more diverse and often less-wealthy students.

Per-pupil spending in the combined district is roughly $18,400, said Shin Green, a financial consultant for the unified district. By the time the 10-year deal Malibu is proposing ends, Santa Monica students would get about $21,000, Green said. And property tax money possibly available to Malibu students? About $98,000 per student.

Asked about that figure, Wood, the Malibu attorney, just laughed; the calculations are too ridiculous to ponder. Malibu Councilwoman Farrer called the number “inflammatory.” City officials say they have no idea where the district’s numbers come from.

The state Department of Education does not require those wanting to create a new school district to project per-pupil spending over 10 years, so Malibu does not have comparable numbers, said Cathy Dominico, a financial consultant for the city. But for Malibu to reach $98,000 per student, Dominico said, either the tax base in the notoriously slow-growth city would have to triple in the next decade, or the student population would have to drop to 300 to 400. Neither is feasible, she said.

If the Malibu plan were to be approved, SMMUSD officials say, just look at who would get the short end of the stick. A quarter of the students in the combined district qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, said David Soldani, the district’s legal counsel on the secession issue. They largely live in Santa Monica.

“It’s one thing to separate the two [cities],” he said. “But when you take the lion’s share of those resources, you do that to the detriment of where the greatest need is, which is in the Santa Monica area.”

If the Malibu proposal is approved, Kean said, the new Santa Monica district would have to start making cuts in the first year to prepare for what he called the financial “cliff” the district would fall off in Year 11.

The first impact, he said, is that the district would have to lay off teachers at Santa Monica’s Title I schools — in which 40% or more of the student body receives free or reduced-price lunch — and class sizes would increase.

Then, some instructional aides at elementary schools would be cut. Next to face the chopping block would be music programs in elementary schools; those programs in secondary schools also would be reduced, he said.

“To take this away would irreparably damage what makes us a high-achieving district,” Kean said. “History has taught us that the cuts are going to be borne by the ones who can least afford it.”

::

What brought these two communities together to educate the region’s children? An accident of history and geography.

The Chumash were in Malibu first. Then the Spaniards. Frederick Hastings Rindge and his wife, May, bought Rancho Topanga Malibu Sequit, a 13,300-acre Spanish land grant, for $10 an acre in 1892.

May Rindge fought off the outside world for nearly 40 years, but what would eventually be named Pacific Coast Highway sliced its way through the rancho in 1929. The Great Depression slowed development. By the time the depression ended, May Rindge owed millions in back taxes, and the family began selling off land. Subdivision followed.

By 1953, Malibu Township had a population of just over 2,300 and two elementary schools, and decided to join a school district. Santa Monica was the closest.

But it’s not that close. Until Malibu High School opened in 1992, teenagers who lived in the neighborhoods of the city that were farthest north would drive more than 30 miles each way to get to Santa Monica High School. Malibu High and Santa Monica High aren’t even in the same league for school-based competition.

When it comes to “common community interests,” Farrer said, “whether it’s places of worship, commerce, shopping, Malibu and Santa Monica don’t mix.”

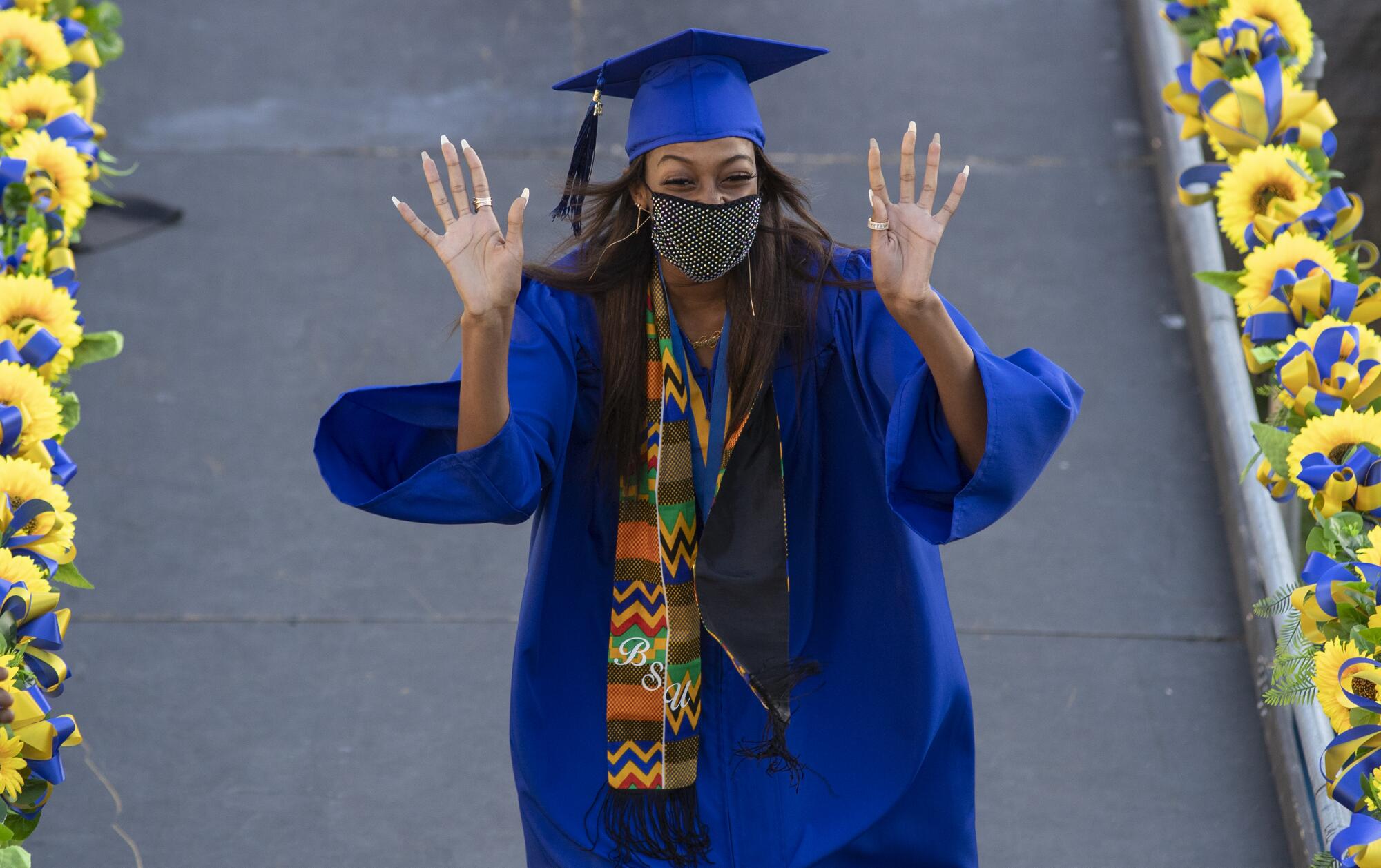

The differences were in high relief at high school graduation. Santa Monica High School seniors filed into Memorial Greek Theater, the school’s outdoor amphitheater, during two socially distanced ceremonies for the nearly 700 graduates, including 60 candidates for valedictorian.

One day later and 21 miles west on Pacific Coast Highway, Malibu High seniors and their families were scattered across a small segment of the football field.

There were so few seniors at Malibu High — 148, 10 valedictorian candidates — that each had time to pose for professionally shot photographs, one while receiving a diploma, one with Principal Patrick Miller. Instead of warnings to obey COVID-19 restrictions, there were back flips off the open-air stage.

At Santa Monica’s graduation, questions about the proposed school district split were met with shrugs. In Malibu, passions ran high.

“I think Malibu should leave,” said Felix de Raspide Ross, a rising sophomore. “Santa Monica is taking a lot of resources. Students over here are getting a more degraded education than Santa Monica.”

::

The future of the district is in the hands of the Los Angeles County Committee on School District Organization — and ultimately, the California Department of Education. In April, more than 300 people gave up a Saturday to publicly voice decades-old complaints — and to discuss the latest demographics.

Malibu held tight to its main point of outrage: Santa Monica just wants it for its money. Santa Monica dug hard into diversity issues and alleged that its smaller neighbor wants to set up what would amount to a mostly white private school district paid for with public funding.

Malibu schools, on average, are 76% white. Santa Monica’s are 54% Black, Latino and Asian.

Heather Anderson, whose two children graduated from Malibu High, likens the conflict to something out of the Brothers Grimm, with Santa Monica as the wealthy, pampered stepsisters, and Malibu as Cinderella, forced to “wash their ball gowns.”

Jon Katz, president of the Santa Monica Democratic Club, charged that the Malibu petition would “create one of the whitest districts in the country.” He bristled at what he described as “multiple classist” comments made by supporters of the current proposal, assertions that Malibu has a “diversity of heart.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Kean, the school board president, who supports the divorce, described the April hearing as “an airing of personal grievance” — which is fine, he said, “but airing personal grievances is not a reason to split.”

The second half of the committee hearing is scheduled for Sept. 18. After that, the panel will give the petition either a tentative OK or a thumbs-down.

The committee will consider nine criteria, laid out in the state education code. Among them: The districts affected should have at least 1,501 students, barring extenuating circumstances; the proposal should not disrupt educational programs; reorganization must not promote racial or ethnic discrimination or segregation; and it should not increase costs to the state.

On Thursday, the committee’s staff and financial consultants released an independent analysis concluding that Malibu’s plan does not meet eight of the nine criteria and would have dire consequences for the financial health of the remaining Santa Monica school district.

If the committee votes yes on Malibu’s plan, there would be public hearings in Santa Monica and Malibu and further study of the split’s feasibility. Then the state Department of Education would make a final decision. In the second scenario, the county committee would rule that the district should remain intact. No appeal to the county is allowed.

Still, another group could put together another petition.

And divorce proceedings could begin anew, moving toward yet another decade of discord.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.