Column: They’re going door to door in Watts answering vaccine questions, and it’s working

- Share via

The vaccination site at Ted Watkins Memorial Park in Watts got off to a slow start when it opened in mid-June. A medical team from the L.A. County Department of Public Health had plenty of vaccine and eager staffers, but very few patients.

Cynthia Key, a public health nurse, got tired of that in about two days.

For the record:

3:19 p.m. Aug. 9, 2021An earlier version of this article quoted Dr. David Bolour as saying, “Yeah, we had lots of stuff and we’re like, ‘What are we doing here? Let’s go.’” He said “staff,” not “stuff.”

“We were just sitting here and needed to utilize our resources properly,” Key said.

“Yeah,” said Dr. David Bolour, “we had lots of staff and we’re like, ‘What are we doing here? Let’s go.’”

From the beginning of the pandemic, infection rates have been high in low-income communities of color, and vaccination rates have lagged below average. Key figured that if the goal was to make vaccinations more accessible, and to provide information to people who were hesitant, the team needed to work harder.

Over the next few days, balloons were flying outside the gymnasium where the vaccinations are administered. Key knew that would lure parents driving by with kids. Vaccines were available for everyone 12 and up. Fliers were printed in English and Spanish.

And then, rather than wait for people to come to them, the medical team went to the people. Before long, lines had formed and the gym filled up.

“In the first days after we opened, we had 15 or 20 people a day, maybe 30,” Bolour said. “Now it’s over a hundred every day.”

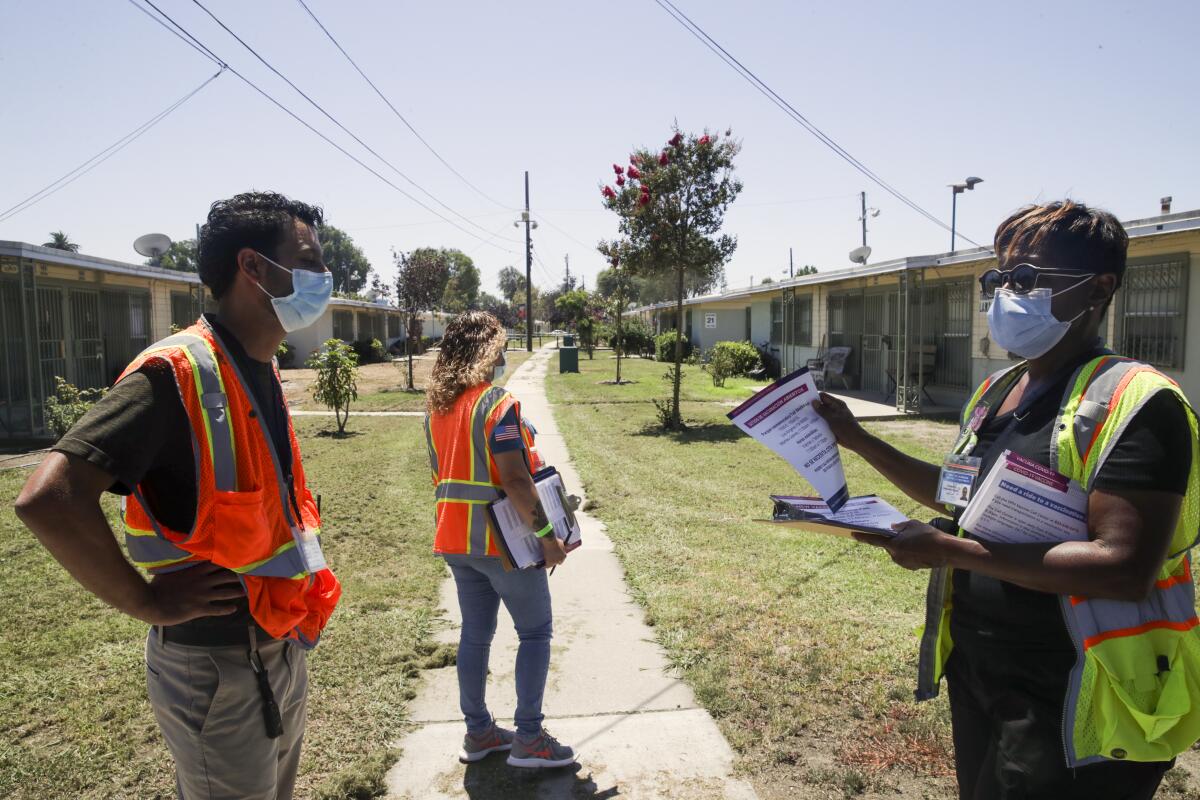

On a sun-blasted day this week, the orange-vested outreach team crossed 103rd Street and headed toward the Gonzaque Village housing project. Three teenage girls were walking west when Key introduced herself and told the girls the medical crew was there in support of the community.

“My grandpa got COVID, but he didn’t die,” one of the teens said.

The national project to stem the spread of COVID-19 has stalled as it meets resistance to vaccinations in large parts of the conservative South and Midwest.

“Most of us will recover,” Bolour said. “But that small percentage of those who die adds up to … 4 million people. … That’s not to say you’re likely to die if you get COVID, but it’s a much higher risk than we’re used to with other viruses.”

The team is careful about its approach, listening carefully to reasons for hesitancy and making sure not to come off as too pushy or strident. Key, who is Black, said she understands the history of distrust in government.

There’s been a recent uptick in vaccinations statewide, due possibly to fear of the highly contagious Delta variant or some employers requiring proof of vaccination. Bolour said he has mixed feelings about mandates, which could make resisters all the harder to reach. In Watts, the outreach team’s approach is to answer questions, offer information and address misunderstandings.

But not to pressure anyone.

“Can I share with you one other statistic?” Bolour asked the three girls. “In June,” he said, when thousands of people died of COVID-19, “99% of them were unvaccinated. So that’s showing us that this vaccine is working really well to prevent death, and that’s our main purpose.”

Key and Bolour said those who are hesitant, or adamantly opposed to the vaccine, give a wide range of reasons. The most common ones include religious faith and a belief in God’s way, a fear that short- and long-term side effects from the vaccines are understated or unknown, and distrust as well as resentment based on a perception that communities of color were last in line.

But as the outreach teams knocked on doors in Gonzaque Village, they encountered as many vaccinated people as resisters.

“I have grandkids, and I want to protect myself and protect them,” said resident Linda Hawkins, who was vaccinated April 7. She said she lost an aunt to COVID-19, and her whole family got vaccinated after that.

“There are people who will argue negatively about it, but there’s nothing worse than being in a grave,” Hawkins said.

Her neighbor, Tina Ferrell, said she got vaccinated without hesitation, and she tells others they ought to join her.

“I went to Smart & Final and there was a guy in there talking about how his whole family got it, but he was scared. And I said, ‘Let me tell you something. When we were young, the schools made us get vaccines. ... What’s the difference now?’” Ferrell said. “This is something that’s going to save our lives … and you got more people getting hospitalized that didn’t take the vaccine than the ones who did.”

Theresa Rogers said she had not been vaccinated but heard something about a new strain and an uptick in cases. Bolour told her the Delta variant was indeed on the rise, and more contagious if not more deadly.

“I went to a funeral and I had two masks on my face and gloves on my hands, and I told people, ‘Stay six feet away from me,’” Rogers said.

She told Bolour he’d be seeing her again soon, because she was ready for her shot.

“I’m gonna come up there,” Rogers said, “because I’m not fixin’ to get sick and be laying down looking stupid.”

Nearby, a Spanish-speaking woman answered her door and heard the team tell her vaccines are available, along with transportation for anyone who needs it. She asked if her kids were eligible and said she’d visit the park soon.

Barbara Ferrer, the county public health director, told me she had been out with the Ted Watkins crew and liked what she saw.

“The personal relationships, for people who don’t trust this vaccine, are what’s going to make all the difference,” said Ferrer, who told me this kind of outreach is now being used at two other county sites and could possibly be expanded. “We told people in Watts we’re not leaving … until we’re doing better in terms of getting more people vaccinated.”

Bolour said some people have greeted them with a curt “no thanks.” But he’s encouraged by the number of people who were initially resistant later came around, including one man with a fear of needles.

“He wanted to squeeze my hand,” Bolour said, “and he squeezed it really hard while the nurse was putting the needle in.”

The team also has information booths set up in the park, and for those who want to know the science behind the virus and the vaccine, Bolour came up with an educational tool he borrowed from his young son — magnetic building block tiles. Arden Cruz, 21, was walking by on her way home from her warehouse job when a nurse, Lynda Desgages, asked if she’d like to see a demonstration.

Bolour took several magnetic squares and made a cube, then surrounded it with triangles.

“The virus is a box of RNA with some spike proteins around it,” Bolour said, shifting pieces around on the table to explain how the vaccine makes it difficult for the virus to attach to cells and multiply.

“Honestly, I’ve read up on everything,” said Cruz, who told Bolour that her mother was vaccinated and wanted Arden and her brother to get jabbed, too.

If you have long-term symptoms of COVID-19 or any other condition, navigating the healthcare system can be rough. Tips for getting the care you need.

Cruz said she has worn a mask and gotten tested regularly, and hadn’t seen a need to do more than that. But after Bolour’s 3-D depiction of how viruses attack the body and how vaccines shut the door, Cruz said she might just go home, get her brother, and come back later for a vaccination.

A promising encounter, for sure, but they don’t all go that way. Bolour and Key walked across the park to a spot where Key had found strong resistance previously among some middle-aged men, and they were still standing their ground.

One of the men told Bolour there is no virus and there is no vaccine — it’s all a sham. He insisted that widely discredited claims of magnets sticking to the skin of vaccinated people are in fact true, and he didn’t give Bolour much of an opening to counter those notions.

Another man, Tharon Bingham, had his own reasons to avoid the needle.

“A lot of people in the ghetto feel like we should stay away from that,” said Bingham, who argued that it makes no sense to put an untested foreign substance into your body if you’re healthy. He said the rise of the latest variant is proof that the science is shoddy, and he said that if these vaccines were so important, why did they take so long to get to communities of color?

“The ghetto is not gonna roll with that,” Bingham said.

Key, who worked at the massive Forum vaccination site In Inglewood before her current assignment, told Bingham she could relate to some of his concerns and criticisms. But she also told him that nearly all the most recent deaths involved unvaccinated people.

That appeared to be news that Bingham hadn’t heard, and he paused to think it over.

Before leaving to return to the gymnasium at the other end of the park, Key told Bingham he probably hadn’t seen the last of her.

“We’re here and we’re going to stay,” she said. “I’m going to keep coming through here and you’re going to see my face, and one day you’re going to say, ‘Let me come down there and see what’s really going on.’”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.