California’s long history on assault weapons on the line in court battle

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — Born of a long history of gun violence, California’s pioneering assault weapons ban was enacted in 1989 after a herculean effort by lawmakers driven by outrage over a mass shooting at a Stockton elementary school.

Legislators said they had to overcome a years-long grip on the Capitol by the National Rifle Assn. and shift strategies to pass the first-in-the-nation law.

But now, after a federal judge’s ruling declared it unconstitutional, gun safety advocates fear California’s trailblazing work is in jeopardy, concerned that the decision could help unravel decades of hard-fought progress here and across the country.

U.S. District Judge Roger Benitez on June 4 issued a permanent injunction against enforcement of much of California’s ban on purchasing assault rifles. State Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta has appealed the Benitez ruling, saying the state’s “strong common sense gun laws help curb not only mass shootings but gun violence as a whole.”

Last month, a three-judge panel of the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals put Benitez’s ruling on hold pending decisions in gun cases that are now before the court.

Benitez’s take on the law is not shared by most California voters, 56% of who don’t believe that the assault weapons law violates the U.S. Constitution, according to a poll released Thursday by the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies and co-sponsored by the Los Angeles Times.

The state law prohibits the manufacture and sale of assault weapons, but allows those who possessed guns before they were restricted to keep them as long as they register them with the state.

As of December, there were about 185,569 assault weapons registered with the state Department of Justice.

Advocates for gun safety laws are concerned the ruling could lead to action by the U.S. Supreme Court that would put other state and federal gun laws at risk.

After California adopted the nation’s first assault weapons ban in 1989, a half-dozen other states and the District of Columbia followed with similar laws, while Congress acted in 1994.

“California is the incubator for every major gun law in the country,” said Kris Brown, president of the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence. “It’s no surprise that the federal assault weapons ban looked a lot like the California assault weapons ban.”

California banned assault weapons after years of bloodshed as criminal street gangs increasingly used the deadly firearms, and residents were shocked by mass shootings that included the 1984 massacre at a McDonald’s restaurant in San Ysidro. A lone gunman armed with an Uzi assault weapon went to the busy restaurant and killed 21 people and wounded 19, the deadliest rampage in the nation by a sole shooter at the time.

At the state Capitol, gun groups including the National Rifle Assn. had long held sway, easily quashing legislation that might have increased regulations of firearms, said former Assemblyman Mike Roos, a Democrat from Los Angeles.

Roos recalls proposing a bill to require a waiting period for buying rifles.

“I got my a— handed to me. I couldn’t even get it off the Assembly floor,” he said.

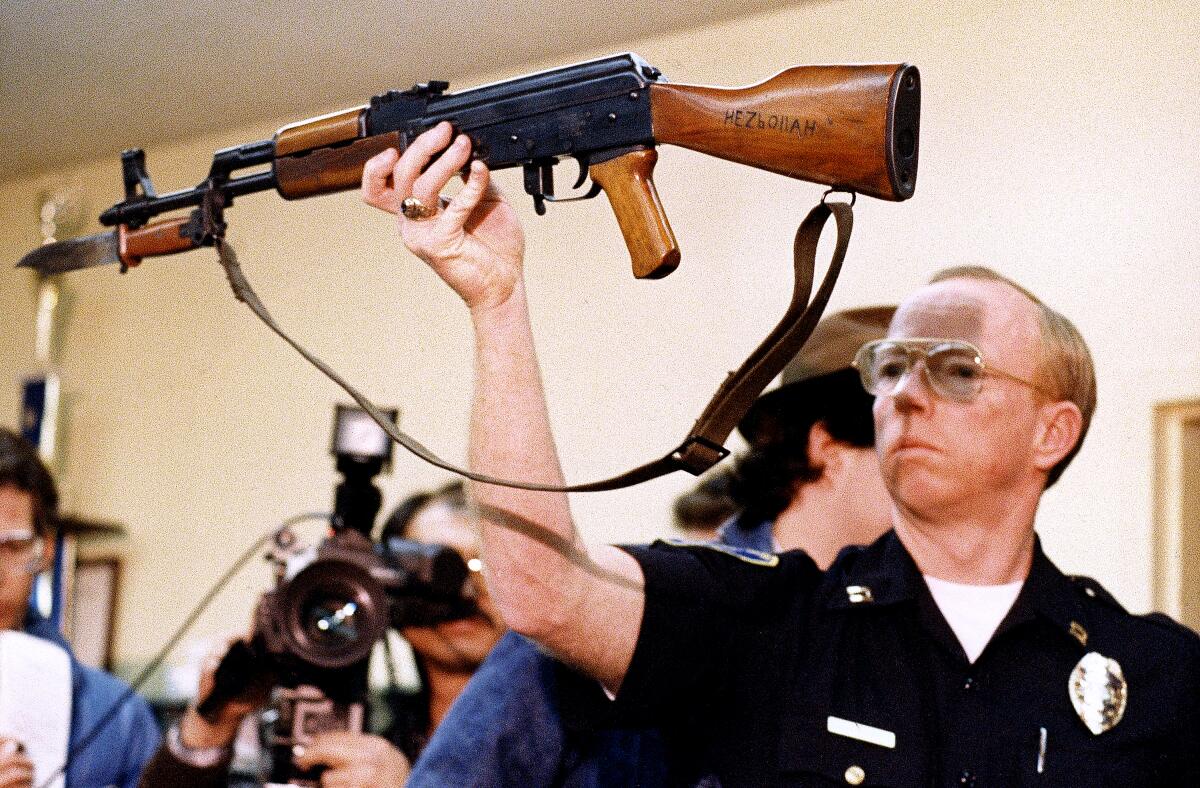

Then on Jan. 17, 1989, a man who professed hatred for Southeast Asian immigrants took an AK-47 semiautomatic rifle to Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton and opened fire, killing five children and wounding about 30 others before killing himself.

Lawmakers were “horrified,” Roos said, adding that a ban on assault weapons proposed by him and state Senate President Pro Tem David A. Roberti of Van Nuys began to see a groundswell of support in the Capitol.

Nevertheless, the push for the assault weapons law was a tough campaign that included a major shift in strategy.

An original proposal had a generic definition for assault weapons but “applied to too many weapons that were popular with hunters and the sporting community,” Roos said.

To make the bill workable, Roberti, Roos and their staffs went through gun catalogs and listed in the bill some 60 makes and models of guns that they considered assault weapons that should be banned.

To line up votes, Roos recalled, he took some of his more reticent colleagues to the California Highway Patrol shooting range for a demonstration of the devastating firing power of assault weapons.

An assault weapon “has such a high rate of fire and capacity for firepower that its function as a legitimate sports or recreational firearm is substantially outweighed by the danger that it can be used to kill and injure human beings,” the Legislature declared in adopting the ban.

Democrats supporting the legislation were also concerned that the governor at the time was a Republican, George Deukmejian.

But Roos said Deukmejian met with the two Democratic bill authors and allowed them to make their case.

“He was just so sobered in terms of the logic of the questions and the ultimate conclusion that there was no party served by having these weapons available in every gun store with no questions asked,” Roos recalled.

Deukmejian signed the Roberti-Roos Assault Weapons Control Act in May 1989, citing the Stockton slaying of “five beautiful young children” just months earlier and saying he hoped the gun bill would help “save innocent lives.”

Legislators expanded the statute several times over the later years, including in 1999 when the Legislature approved SB 23, which added to Roberti-Roos a definition of what constitutes an assault weapon to address modifications manufacturers were making to the guns listed in the law.

The new law said banned assault weapons also include a semiautomatic, centerfire rifle that has the capacity to accept a detachable magazine and has a thumbhole stock, a second handgrip, a folding or telescoping stock, a flash suppressor or a pistol grip that protrudes conspicuously beneath the action of the weapon.

But in Washington, the federal assault weapons ban expired in 2004 without congressional action.

Californians strongly support their gun laws, according to polls by UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies.

A 2018 poll found 67% of California voters surveyed favored banning the sale of assault weapons nationwide, more than twice the number —29% — who were opposed.

The poll released Thursday found that 56% of the state’s voters surveyed believe stronger laws restricting the sale and possession of guns help make their communities safer.

The California attorney general’s office made that argument in court, telling Benitez that evidence indicates the assault weapons ban is saving lives.

“California’s assault-weapon restrictions are effective in mitigating the lethality of mass shootings and can even reduce the incidence of mass shootings,” then-Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra said in a February filing.

The state’s court brief cited 2013 data by U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that in 1993, some 5,500 Californians were killed by gunfire, but in 2010, the number had dropped by about half to 2,935 people.

In addition, state officials cited findings by the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, which said this year that California has the seventh-lowest gun death rate in the country, an improvement from nearly three decades earlier when California had had the 35th lowest rate.

“California’s gun safety laws make it one of the safest states in the entire U.S. compared to all other states in America,” Brown said. “Per capita, California has among the lowest incidents of gun deaths and injury. All of the folks who have looked at it attribute it to the comprehensive nature of its gun safety laws.”

To prove the point, the state attorney general brought in public safety experts including Louis Klarevas, a research professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, in New York.

Klarevas testified that mass shootings involving six or more fatalities pose the deadliest criminal threat by individuals to American society and massacres involving assault weapons have a higher average loss of life than those without the firearms.

Klarevas’ research compared the 10 years before Congress approved the federal assault weapon ban to the 10 years it was in effect and found a 37% reduction in gun massacre incidents and a 43% reduction in gun massacre deaths.

During the 10 years after the federal ban expired, Klarevas said there was a 183% increase in gun massacre incidents and a 239% increase in gun massacre deaths.

States including California with restrictions on possession of assault weapons saw a 46% decrease in the incidence rate of gun massacres, he said in court papers.

Klarevas noted that since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, assault weapons have been used in seven of the 10 deadliest mass shootings in the United States, including the 2012 Newtown, Conn., school massacre that killed 26 people, including 20 first-graders, the 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting that left 49 dead and the 2017 Las Vegas attack that resulted in 59 deaths during a concert.

More recently, assault weapons were used in the 2015 terrorist attack in San Bernardino that left 14 people dead and at least 21 injured.

The plaintiffs in the lawsuit against the assault weapons ban had their own experts, including John Lott, an economist, gun-rights advocate and author of the book “More Guns, Less Crime.”

Lott concluded in a court filing that “there is no credible evidence that so-called ‘assault weapons’ bans have any meaningful effect on reducing gun homicides and no discernable crime-reduction impact.”

Benitez came down on Lott’s side.

“One is to be forgiven if one is persuaded by news media and others that the nation is awash with murderous AR-15 assault rifles. The facts, however, do not support this,” the judge wrote.

He said that the number of mass shootings in California involving assault weapons was about the same before and after the 1989 law.

“The assault weapon ban has had no effect. California’s experiment is a failure,” the judge wrote.

Among its ramifications, Benitez’s decision could have an impact on gun control efforts across the country, and the push to reinstate a federal assault weapons ban.

“While this victory is most certainly a valuable one, it’s also important to understand how impactful this decision will be in restoring 2nd Amendment rights not only in California but across the entire country,” said John Dillon, an attorney for the Firearms Policy Coalition, one of the groups that challenged the ban. “This landmark trial win points the way to victory everywhere these unconstitutional bans exist.”

Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), who authored the original federal assault weapon ban and has been trying to reinstate it since it expired, said the judge’s ruling is “a clear outlier.”

“Federal appeals courts have routinely upheld assault weapons bans across the country, in part because they reflect the will of the public to try to stop the mass shootings that continue to plague this nation,” Feinstein said in a statement.

Roos said he was “absolutely stunned” by Benitez’s ruling.

But he is also hopeful that the U.S. Supreme Court will not overturn bans on assault weapons, noting the justices also live in a society where the guns have caused death on a large scale.

Still, Brown is worried that the addition of more conservative justices to the U.S. Supreme Court in recent years might make it more open to Benitez’s interpretation of the 2nd Amendment as providing broader protections against gun laws.

“If the Supreme Court were to hold that, it would really upend all of the public safety infrastructure we have put in place,” she said. “The implication for all gun laws in this country is chilling and deeply concerning.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.