‘Heroes, villains, charlatans, enigmas’: Why I followed the Calico story

- Share via

In the 1980s, out of college and eager to explore California, I often headed over the Cajon Pass into the state’s expansive deserts. The 15 freeway took me to Barstow, where I had a choice: north to Death Valley or east into the Mojave.

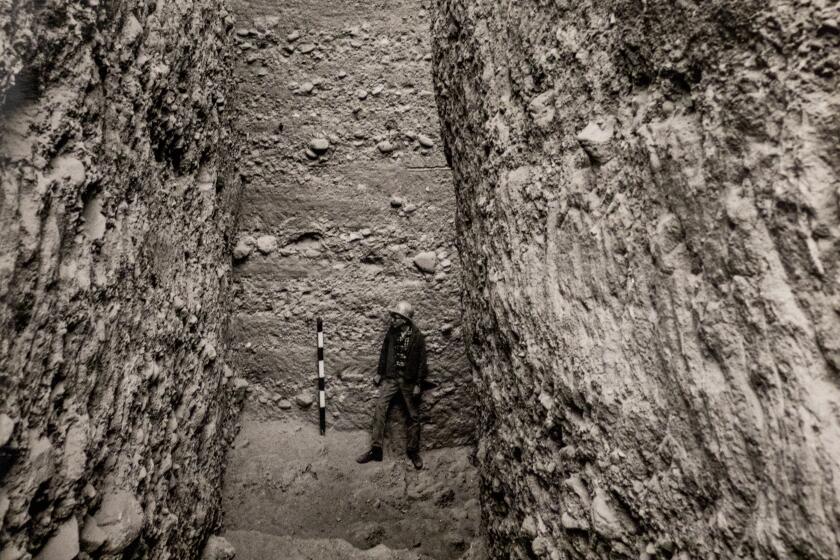

Once I headed east and stopped at the Calico Early Man Site (not to be confused with the Knott’s Berry Farm-infused Calico Ghost Town). I took a tour and peered down an impossibly deep shaft in the ground, whose pebbly walls suggested how difficult it was to achieve such a depth.

The guide spoke of artifacts — stone axes, scrapers — and a claim that was less controversial than it was ridiculous. At the time, no one believed that humans were in the New World more than 13,500 years ago, and here was Calico making the case for 200,000 years ago.

Years later, I read about a site in Texas that some experts were calling “the oldest credible archaeological site in North America.” The word credible caught my attention, and I was reminded of Calico, which had always been considered incredible.

I reached out to a geomorphologist at UC Berkeley, Ted Oberlander, to get his opinion on Calico. “It’s OLD!” he wrote me in a lengthy email that not only confirmed the age but touched upon the decades-long dispute that had engulfed this lonely site in the Mojave.

“The situation re. Calico is a scandal. Nothing less,” he continued. “It would make a great story: an immortal (Louis Leakey), heroes, villains, charlatans, enigmas, clueless commentators. The establishment vs. the upstarts. The Galileo parallel.”

I was intrigued. Leakey? Sure, he had been on site in the ’60s. But Galileo?

After more research, I reached out to the chief proponent of Calico’s ancient history, Fred Budinger, who seemed to be waiting for the call and happily laid out his long association with the site and the enmity that had arisen between him and a group that called itself Friends of Calico.

Initially I was suspicious of Budinger’s zeal. I needed something more than the dating controversy, which I was in no position to adjudicate.

I emailed James Bischoff, recently retired from the U.S. Geological Survey. In 1981 and later in 2007, he had worked with Budinger and dated a few presumed artifacts from the site. In each instance, he arrived at the same conclusion: 200,000 years old.

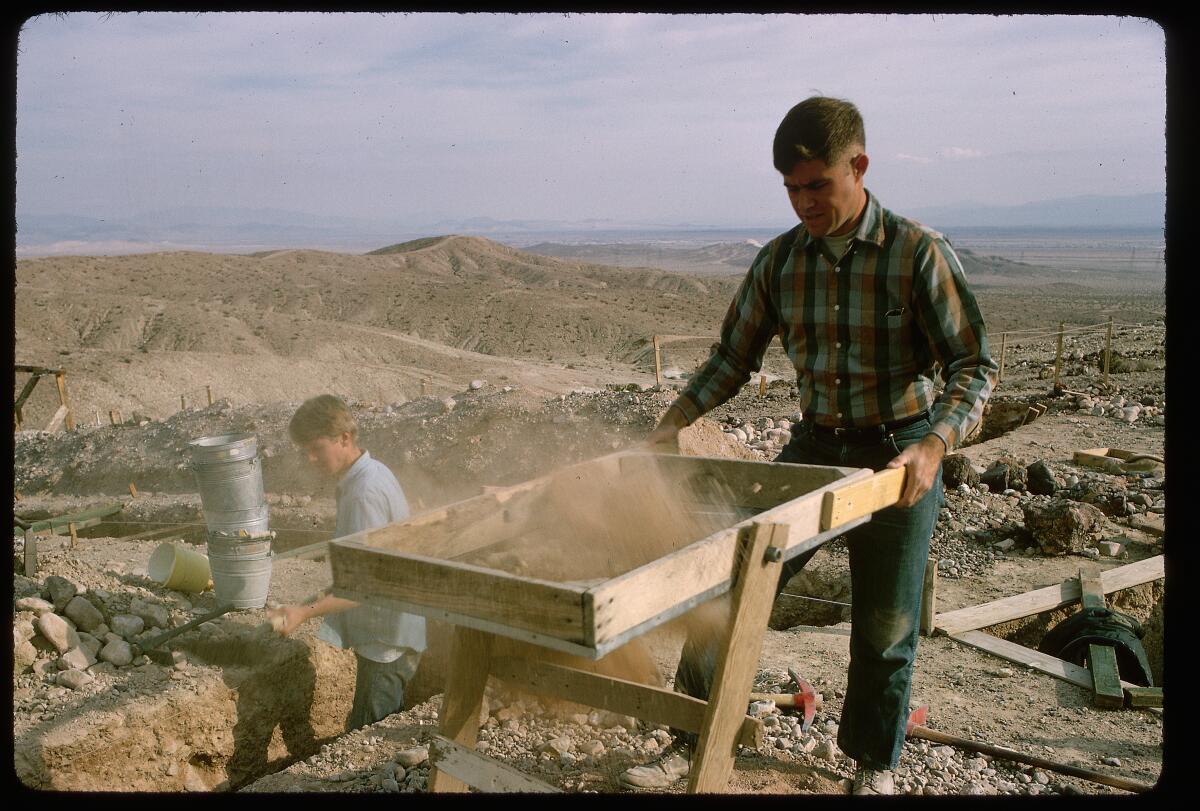

The Calico site in the Mojave Desert for decades attracted expert and amateur archaeologists, digging for evidence that early man roamed the area 200,000 years ago. One man continues that lonely quest.

“I have collaborated off and on with Fred over Calico since the mid-1970s,” he wrote me. “I feel he has been treated unjustly by the board of directors of the Friends of Calico. In my opinion the reason is greed.”

With tales of conspiracy, mishandled funds and even federal neglect, I knew I had found a good story, no matter how buried it was in arcane scientific details, thermoluminescence dating, electronic spin resonance and superconducting quantum interference.

I was less interested in the science than in the devotion. Calico, once a strange and marvelous beacon of science, had become a hot potato, as unlikely a stage for women and men asking the Big Questions — who we are and how we got here — as I could find.

I knew I should not be surprised. The bigger the questions, the bigger the drama, and the participants of this story took nothing in half measure. Even Leakey’s wife, the equally esteemed archaeologist Mary Leakey, recounted in her memoir how she lost her professional respect for him over the Calico debate.

Her explanation was simple: “Of all the places where Louis could count on the adulation that he craved in these latter years, nowhere exceeded the levels reached in Southern California. His audiences there loved him anyhow as a person and a visiting super-star, but the local archaeological community worshiped him even more because he gave them, with the guarantee of his personal infallibility, what they had always wanted: Early Man of their very own.”

I also knew from reporting about a dig in San Diego — where early humans stood about 140,000 years ago — that archaeology can be blood sport, especially if dating is involved.

The Calico story, though, remained in my notebooks. In 2017, I learned that the site had been vandalized, and I contacted the U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s office in Barstow. I wanted to know what had happened. After all, they were in charge with keeping the place safe.

I submitted questions, requested a tour and, as much as the field director promised to get back to me, never got the answers I needed. “Staff has been extremely busy, coupled with leave,” was one reply. “Expect to have a response by the end of the week.”

I chalked it up to federal bureaucracy, but they weren’t the only ones reluctant to help. Adella Schroth was Calico’s project director, and she too avoided me.

“Just hold on to the article,” she responded by email. “We are in the middle of a paper that settles the dating of the site once and for all. Be patient. When the paper is released, I will give you an interview. Anything you print will be questionable, because the dating of the site is still open for debate.”

She died before that interview could take place, and I was getting nowhere. I got the impression that everyone wished Calico would just go away, except for Budinger, who on April 10 of this year sent me an email with a scan of a certified letter he had received from the Bureau of Land Management detailing plans to remove the buildings and fill in most of the pits.

Sensing that Calico’s final chapter was being written, I picked up the story again. By now, it had become more poignant. Bischoff had died. Oberlander was getting up in age, and only a few others were around to talk about the site and its legacy.

I reached out to a former Army paratrooper who lived in neighboring Yermo, had worked as Louis Leakey’s bodyguard and had been hired out of retirement to be Calico’s last caretaker. Chris Christensen, 85, had stories to share: of Leakey’s celebrity and of methamphetamine addicts who scour the desert for anything that can be sold to support their habit.

As for the site’s controversy, Christensen’s assessment was pointed. “There needs to be more research,” he said, “and we need to carry the science to the final conclusion. One of the problems out there is that nothing is ever carried to a conclusion.”

I reached out to the Bureau of Land Management again, and its field director, Katrina Symons, agreed to a tour. Twenty minutes off the 15 freeway, at the Minneola exit, the site lay in ruins. Only one building stood, an empty shell. The others had been torn apart or brought to the ground. The cyclone fencing at the pits had been cut and peeled back.

Soon I was talking with Russ Kaldenberg, who, during his tenure as the bureau’s field archaeologist from 1993 to 2003, had written a defense of Calico, which he called “a national treasure.”

I spoke to Meg McDonald, a former treasurer of Friends of Calico. I texted Katie Boyd, a former president, who maintains a small exhibit on the site at a museum in Barstow, and I emailed Chuck Williams, who had worked in the pits in the early 1960s and had his own theories about the artifacts.

Finally, I emailed Schroth’s coauthor on two unpublished papers with the intention of putting the mystery of Calico to rest. Yet, in keeping with the mystery, the coauthor tried to wave me off the story (“I don’t think this is the best topic ...”) and requested anonymity (“Please don’t disclose any of what I’ve disclosed”).

As the reporting was coming to an end, I visited the San Bernardino County Museum, where almost a dozen of the most prized artifacts are stored in Ziploc bags inside a metal box inside a vault. To see these objects, I had to receive permission from the Bureau of Land Management, which owns the collection, and I was accompanied by its archaeologist, Jim Shearer.

Most pieces were removed from Calico during the 1960s and are tagged with slips of paper identifying where they were found. “One of the modified pieces which caused Dr. Leakey to decide to excavate Master I,” read the neat cursive script, dated May 11, 1963, attached to one artifact.

Meanwhile, in a nearby office park are 68 bankers boxes, stacked on shelves from floor to ceiling, stuffed with more presumed artifacts. They had joined other spillovers from the museum — old typewriters, a hearse on a sled, spinning wheels and looms — that have no other place to go.

Finally, I visited Budinger at his home in San Bernardino, and in the course of our conversation, Calico — this place of outsize ambitions, egos and claims — was brought down to scale, animated by his passion, his sadness, his betrayal and dedication.

“This was home,” he said to me one day, and for an instant, I heard his voice crack and understood why I was telling this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.