L.A.’s COVID-19 death rate falls below that of Bay Area in another sign of widening recovery

- Share via

For much of the pandemic, the San Francisco Bay Area managed to limit the spread of the coronavirus far more dramatically than Los Angeles County, which ended up as one of the nation’s hardest-hit regions.

But in a sign of its dramatic recovery, L.A. County reported about two COVID-19 deaths a day over the past week, down from a peak of 241 in January. By comparison, the Bay Area — comprising Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, Napa, Santa Clara, San Francisco, San Mateo, Solano and Sonoma counties — is reporting four deaths a day, down from a peak of 63. L.A. County has a population of 10 million; the Bay Area has 7.7 million.

This is just one more piece of evidence about how the course of COVID-19 has changed in California, and why officials are confident that the state faces little risk of the surges that repeatedly shut down large swaths of the economy over the past 15 months.

The Bay Area was an entry point for the coronavirus in California. The nation’s first confirmed COVID-19 death was of a San Jose resident, who died Feb. 6, 2020.

But by April 4, 2020 — a month after Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency over the pandemic — L.A. County’s COVID-19 death rate was worse than the Bay Area’s, according to a Times analysis. That would continue to be the case for more than 14 months, until the streak ended June 11.

During the height of the pandemic in January, for every 100,000 residents, L.A. County was reporting 2.39 deaths a day, while the Bay Area reported 0.82.

But by Thursday night, L.A. County was reporting 0.02 deaths a day for every 100,000 residents, compared with 0.06 in the Bay Area.

As of Tuesday, restrictions were lifted at most businesses, and Californians fully vaccinated for COVID-19 could go without masks in most settings.

L.A. County’s recent improvement is a result of two factors. First, there has been a respectable vaccination effort: 57% of residents of all ages are at least partially inoculated, better than the national rate of 53%. Second, the county has significant residual immunity from a COVID-19 surge that began in November and continued into the winter. In late May, the L.A. County Department of Health Services estimated that nearly 40% of residents had acquired natural protection from surviving COVID-19.

But a deadly surge isn’t necessary to get to the other side of a pandemic; keeping people healthy until a vaccine emerges can be an effective strategy. The Bay Area did a better job of that than L.A. County. The northern region has reported more than 6,200 cumulative COVID-19 deaths — one-quarter of L.A. County’s toll of more than 24,400.

On a cumulative basis, the Bay Area reported 81 COVID-19 deaths for every 100,000 residents, while L.A. County reported triple that, at 242.

Experts say the Bay Area was relatively spared over the winter for several reasons, including more public support of pandemic restrictions and lower rates of social vulnerability, which is affected by poverty, crowded housing and lack of access to transportation.

Now, both regions have their lowest death rates since the first few weeks of the pandemic, even if they took different paths to get there.

California fully reopened Tuesday, so residents who are fully vaccinated were able to go into many public places without masks, but many kept them on.

L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer this week marked the reopening of California’s economy with pride, while acknowledging the heartbreak of the death toll.

“We are able to come together to commemorate this milestone with a sense of relief and optimism in our hearts,” Ferrer said. “There were many times during this past year when it was hard to believe we would ever feel these feelings again.”

The state’s reopening, she continued, means “parts of our lives will go back to something that feels almost normal. We can — and we should — feel joy while recognizing and honoring the immense collective effort that brought us to the point where we can now do this.”

During the worst moments of the pandemic, hospitals across L.A. County were overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients, and hospital morgues and mortuaries were so full that the National Guard was called in to help transport corpses to the county coroner’s office for storage. Air-quality officials were forced to suspend daily limits on cremations to prevent the public health crisis of a backlog of bodies.

Although health experts see reason for confidence as California ends many COVID restrictions, here are some dangerous health scenarios they’ll be watching out for.

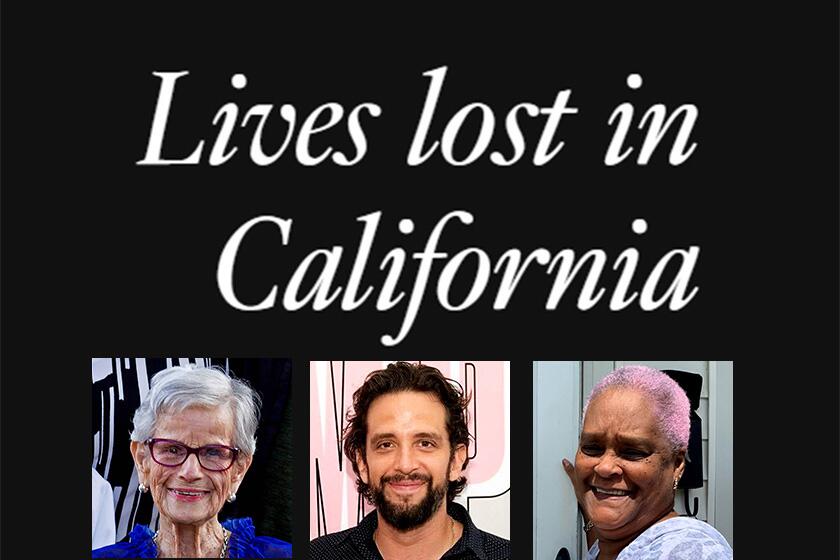

Over the course of the pandemic, members of L.A. County’s most vulnerable communities — including the Eastside, South L.A. and the southeast part of the county — were hit hardest; particularly affected were those forced to leave home to work and those who live in crowded conditions. Among the dead: Jose Guadalupe Zubia, 59, a mechanic who lived with two sons and two daughters; Mariano Zuñiga Anaya, 57, a doting grandfather who lived in Florence-Firestone; and Chouphaphone “Judy” Bounthong, 58, a surgical tech at Emanate Health Queen of the Valley Hospital, who used to bring food and supplies to the homeless people near her West Covina workplace.

The toll could have been worse. While overwhelmed, hospitals in L.A. County were never forced to systematically ration healthcare for long periods of time and were not required to choose which sick patients would get care and which would not. L.A. County’s hospitals managed to avoid the kind of meltdown that occurred in New York City early in the pandemic.

A factor that likely helped both L.A. and the Bay Area in the early months of the pandemic was the implementation of stay-at-home orders soon after the coronavirus was detected in California, keeping levels of disease relatively low for months as healthcare experts developed better treatment options.

Officials also believe L.A. County’s controversial order to shut down outdoor restaurant dining just before Thanksgiving helped prevent a greater catastrophe.

An analysis by the county Department of Health Services later found that the effective transmission rate of the coronavirus began declining in late November — around the time the ban on outdoor dining went into effect. But it was many weeks before the results of that change were seen in hospitals — a lag that occurred due to the time it takes a person infected with the coronavirus to become sick enough to require hospitalization.

L.A. County’s actions helped pave the way for more comprehensive stay-at-home orders in early December in the state, excluding rural Northern California.

Now, the L.A. metro area has one of the lowest daily coronavirus case rates among other comparable areas, according to the organization COVID Act Now, with fewer cases than the metro areas of New York City, Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Miami, Philadelphia and Atlanta.

California has for weeks recorded one of the lowest daily coronavirus case rates in the nation. And more than 69% of California residents who are at least 12 years old have received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Still, there are concerns. The virus could spread among clusters of unvaccinated people — and L.A. County’s young Latino and Black residents are less likely to have received the vaccine than white, Native American and Asian American residents. It could be months before L.A. County reaches “herd immunity,” the point at which a significant percentage of the population is immune to the disease, indirectly protecting people from infection, Ferrer has said.

“We need to continue to get vaccines and high-quality information to people who aren’t yet vaccinated,” she said this week.

In the meantime, she added, “unvaccinated people need to remain very careful and wear masks,” and people who do get sick need to stay home.

Some promising statistics show high rates of overall immunity when factoring in people who survived COVID-19 but haven’t been vaccinated. The California Department of Public Health recently estimated that 73% of L.A. County residents has immunity, based on either prior infection or vaccination. (The state warns that this may not be representative of California’s general population.)

The overall immunity rate in a region that includes the Bay Area, as well as Santa Cruz and Monterey counties, is estimated to be even higher: around 81%.

With California set to reopen its economy fully on Tuesday, wearing a mask will become optional in many public settings. Here are the rules.

Even the most cautious health officials in the Bay Area have voiced optimism that the worst has passed.

“Our case counts may vary — it may go up and down. But I don’t expect it to surge back up,” Dr. Sara Cody, the Santa Clara County public health director and health officer, told the Board of Supervisors recently.

Dr. Christina Ghaly, the L.A. County health services director, stressed that California’s reopening was not the end of the pandemic in the state, given how many residents remain unvaccinated, including children under 12, who are not yet eligible.

She urged vaccinated people to tell unvaccinated people why they got their shots.

“The vaccine is safe. The vaccine is effective. And the danger of not getting vaccinated is very real,” Ghaly said. “If you have received the vaccine, tell others about it; tell your story. Tell people why you chose to be vaccinated.”

The San Francisco order will go into effect once the FDA gives formal approval for one of the COVID-19 vaccines.

All three vaccines approved in the U.S. are effective against all known variants of the coronavirus.

Meanwhile, California’s economy is poised for a “euphoric” comeback, according to a UCLA Anderson forecast, powered by strong tech and business sectors and a boost in home building.

The report said California suffered less of an economic contraction last year than Texas and Florida, states that imposed fewer COVID-19 related restrictions.

Nearly 63,000 Californians have died of reasons related to COVID-19. The national COVID-19 death toll surpassed 600,000 on Tuesday.

Times staff writers Maria L. La Ganga, Brittny Mejia, Joe Mozingo and Margot Roosevelt contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.