Newsom proposes transitional kindergarten for all California 4-year-olds in budget plan

- Share via

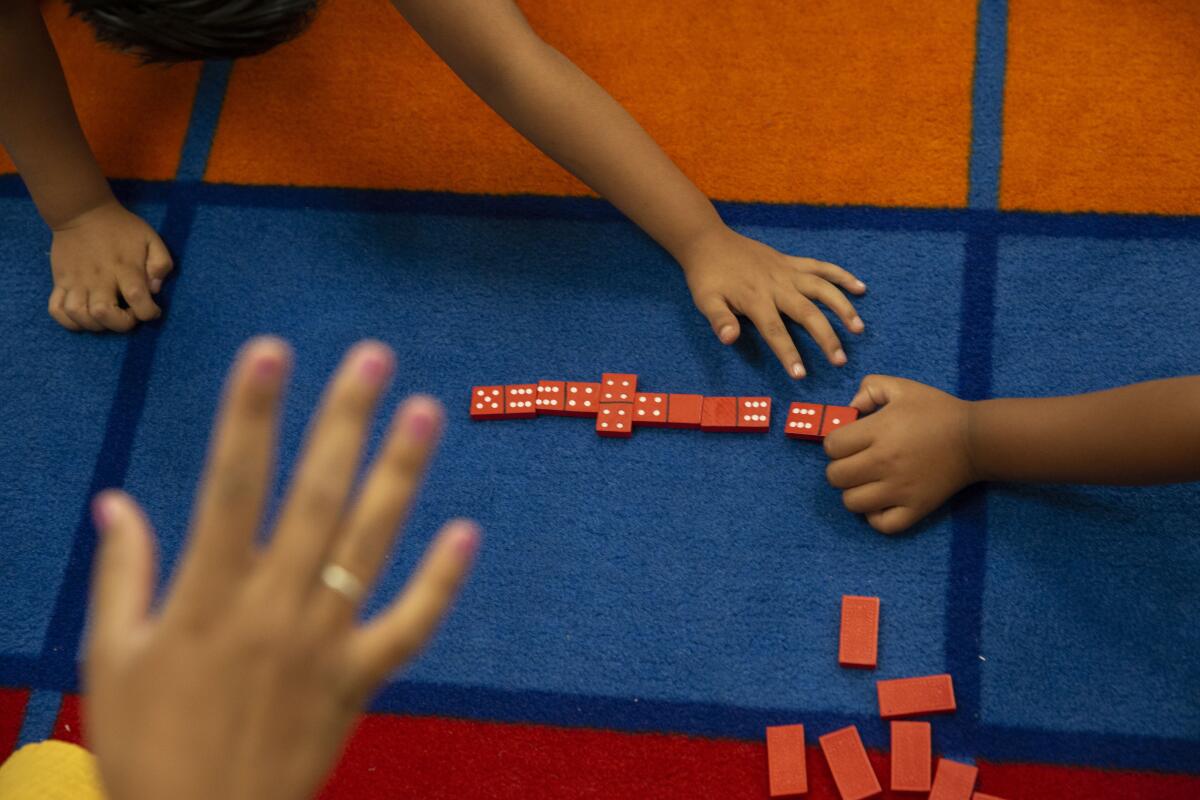

SACRAMENTO — Transitional kindergarten, currently available only to about one-third of California’s 4-year-olds, would be expanded to all by the 2024 academic year under a proposal unveiled Wednesday by Gov. Gavin Newsom, part of a wide-ranging multiyear, multibillion-dollar commitment to education targeted to help students most in need.

The governor said the emphasis on early education, by adding a year of school on the front end, is appropriate given the experience of the youngest learners.

“It’s a readiness gap as much — more than it is an achievement gap,” Newsom said. “People are not left behind as often as they … start behind.”

The expanded transitional kindergarten program would take effect for the 2022-23 school year and would be phased in over three years.

Funded by unprecedented growth in state tax revenues, the effort is one of a series of far-reaching education proposals Newsom will send to the Legislature at the end of the week in his revised state budget. Those plans include additional after-school and summer programs in low-income communities, $4 billion for youth mental health support, more than $3.3 billion for teacher and school employee training and $3 billion to encourage the development of “community schools,” where education is integrated with healthcare and mental health services in communities with high poverty rates.

The state would also establish a $500 college savings account for every California student from a low-income family with an additional $500 for foster youth and those who are homeless. The $2-billion program would be funded mostly by a portion of the state’s share of money from the American Rescue Plan, signed into law by President Biden in March. Estimates are it could provide a savings account for as many as 3.8 million California schoolchildren.

The plan was greeted enthusiastically by Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the state Board of Education and a Newsom ally.

“This set of investments and reforms will catapult California forward and really allow us to reinvent the public school system in this state,” said Darling-Hammond, who also appeared at the event, which was held at Elkhorn Elementary School in the North Monterey County Unified School District.

That school was chosen because it provides services for students and families from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. — a model, officials said, for what the governor’s proposal envisions.

For school districts, the funding proposal is expected to bring an unaccustomed flood of state and federal resources as educators plot out a recovery from yearlong pandemic-forced campus closures.

Even without this proposed infusion, Los Angeles Unified, the state’s second-largest school system, was looking at one-time aid well in access of $5 billion since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Enormous amounts already have been spent on safety measures, technology, and student and staff support; enormous amounts remain to be spent.

But most of the previously allotted funding is one-time money, whereas Newsom’s proposal envisions a permanent expansion of the state’s education offerings and strategy. His focus lines up with the recommendations of many experts, who note that an early start to academic and social development for youngsters has been out of reach for many, especially children from low-income families.

The pandemic has exacerbated such inequities, they said. Moreover, many families simply kept young children out of kindergarten and preschool during the closures rather than position their youngsters in front of a computer for schooling. .

“Universal TK is a tremendous opportunity to build up young learners’ social and emotional skills,” said Hana Ma, senior policy analyst at Education Trust–West, an Oakland-based research and advocacy group. “Kindergarten enrollment dropped tremendously over the past year, and being able to offer transitional kindergarten for all 4-year-olds is a way to engage families when their kids are younger.”

Experts estimate the program would serve almost 300,000 children when it reaches full capacity in 2024, adding transitional kindergarten to virtually every elementary school campus in the state. Because they are part of local school districts, transitional kindergarten teachers make about the same as kindergarten teachers, and significantly more than preschool teachers who serve the same age group.

The phase-in will begin with children who turn 5 between Sept. 2 and Dec. 2 of 2022. The target age will move up by several months each year through the 2024-25 school year.

The gradually increasing eligibility will disappoint parents whose children are currently 4-years-old and won’t receive the benefit. Another issue will be the format of the program. The governor’s office said it envisions up to nine hours a day of supervision, which would include three hours to develop academic skills.

The state’s poorest 4-year-olds already qualify for public preschool, through a mix of district-based transitional kindergarten, state preschool and the federally funded Head Start program. Yet tens of thousands still can’t find a spot, and those who do risk losing it if their family’s income improves.

For Newsom it was the third consecutive day that he traveled across California outlining portions of his yet-to-be presented state budget, a spending plan that he said benefits from $75.7 billion in unexpected tax revenues — equal to more than half of all state general fund spending in the fiscal year that ends on June 30. The governor announced plans on Tuesday for a $12-billion package to address homelessness and on Monday outlined an expansion of the program offering $600 stimulus checks to the state’s middle-class residents.

The windfall of revenues represents an about-face from last spring, when Newsom’s budget advisors expected the COVID-19 pandemic to throw the state’s finances into a severe deficit. Those predictions failed to materialize after California’s high-income earners paid record taxes on capital gains from stocks and other investments.

“You know, last year we were facing a historic deficit, we couldn’t do what we wanted to do. But, boy, is that not the case this year,” Newsom said Tuesday during an event in Los Angeles to promote his plan to spend $1.5 billion to clean public spaces and areas near the state’s highways.

Spending on K-12 schools and community colleges in California is governed by a series of formulas enshrined in the state Constitution by voters, giving public schools the single largest share of general fund revenues. Newsom’s budget, according to advisors, projects guaranteed school funding will surpass estimates in his January spending plan by $17.7 billion — pushing education spending to a record $93.7 billion in the coming fiscal year.

Newsom’s new education plan will make use of dollars that he is required to spend on education. He could simply have forwarded the funds to local school systems — giving them more discretion on how to spend the money. Instead, he decided to leave an imprint by directing the use of this money.

The governor on Friday will formally reveal his full budget proposal, which would need the approval of the state Legislature.

Providing transitional kindergarten for all 4-year-old children will be costly. At full implementation, Newsom’s advisors say the program will cost $2.7 billion a year.

Transitional kindergarten was created by the Legislature in 2010 under a plan that tightened the birth-date rules for children turning 5 and entering kindergarten. Currently, only students who will turn 5 between Sept. 2 and Dec. 2 are eligible for the state-sponsored program. Lawmakers have pushed for those rules to be loosened or removed entirely to give access to all 4-year-olds, with one proposal currently pending in the state Assembly.

In his remarks, the governor described his plan as representing $20 billion of new education investments, although some of this spending will cover multiple years and expand gradually, including dollars committed to before- and after-school programs and to summer enrichment activities.

In response to the governor’s remarks, a coalition of parent groups urged the governor to focus first and foremost on returning the state to a full-time, five-day-a-week instruction.

The governor has insisted he shares this goal, although he’s stopped short of calling for a mandate. On Wednesday, he suggested that a return to a typical on-campus schedule could be codified into state law by June 30.

His plan also calls for robust independent study options — presumably for parents who are not yet ready to return their children to campus in the fall.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.