Column: California’s sluggish population growth has lost us a congressional seat. That should concern us

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — California has now joined the Rust Belt states in losing national political clout because of sluggish population growth.

Should we worry about that?

Darn right!

True, the lost clout is minuscule: one U.S. House seat and one electoral vote in presidential elections. We’ll still have much more than any other state. The loss will barely be noticed — this time.

But is this a trend? The symptom of internal decay? Is the Golden State turning to rust?

No one really knows, but it should seriously concern us and be honestly confronted.

“Sitting back and doing nothing is not the solution, whether it’s on housing or the economy or equity,” Jeff Bellisario, executive director of the Bay Area Council Economic Institute, was quoted in the San Francisco Chronicle.

“It’s a signal to policymakers that we’re not headed in the right direction.”

A little history: In the 1940s, New York — the Empire State — held 45 House seats, the largest bloc in the nation. After losing another seat with last year’s decennial census, New York will be down to 26, a substantial weakening of political muscle over the decades.

There’s no denying it: Results from the national head count released Monday by the U.S. Census Bureau showed that for the first time in our 170-year history, California will lose a congressional seat. Our population grew below the U.S. average after 2010 — at a 6.1% rate, compared to 7.4% for the nation.

They counted 39.5 million Californians, up 2 million from the 2010 census.

That means California will lose one House seat while Texas gains two. Florida and four other states will pick up one each. Seven states will lose one.

But California will still field by far the largest House delegation — 52 members, compared to Texas’ 38.

It could have been worse for California had Sacramento Democrats not acted to minimize the damage. They feared a loss of two seats, mainly because of President Trump’s anti-immigration policies.

Trump tried to ask people during the census whether they were citizens. That would have discouraged those living here illegally from getting anywhere near a census form. Trump also didn’t want to count undocumented immigrants when reapportioning congressional districts. California sued the Trump administration and won.

The U.S. Census Bureau released apportionment data, but the pandemic-induced lag has already caused ripple effects on redistricting and 2022 races.

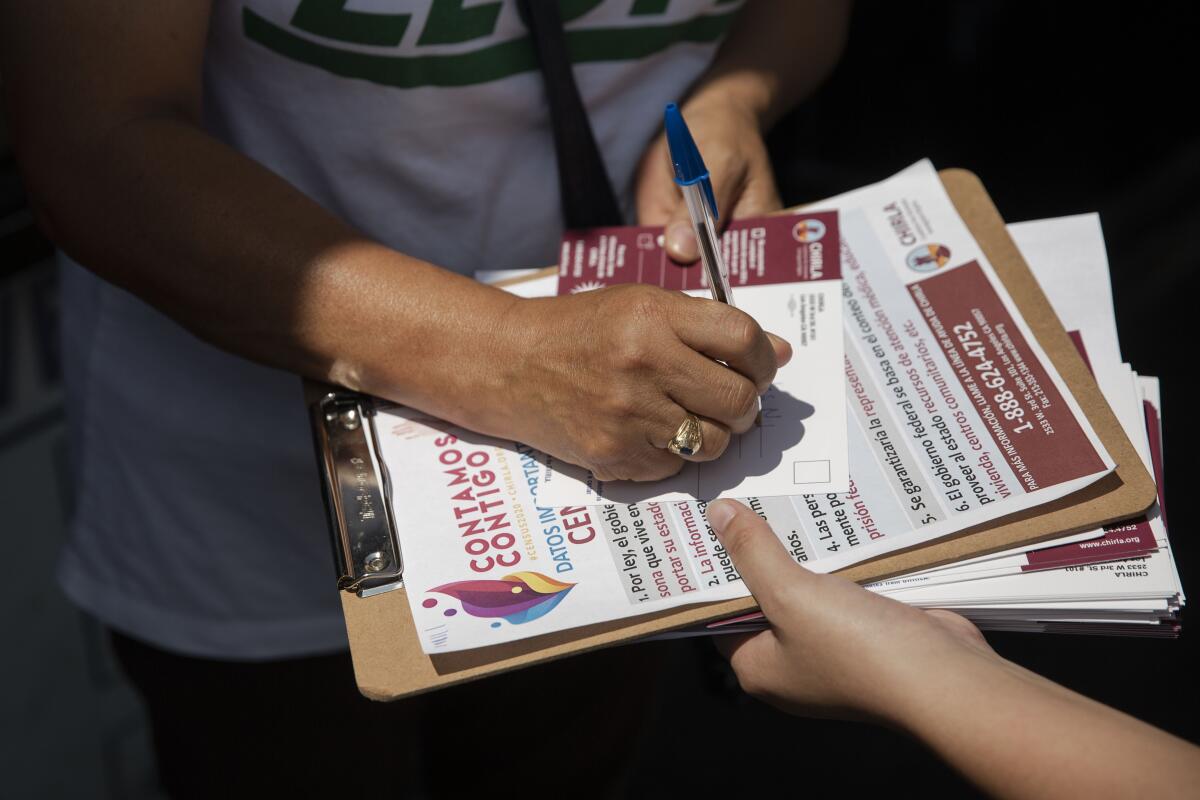

Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Legislature spent $182 million on an outreach program encouraging the “hardest to count” — mainly immigrants — to participate in the census. As a result, 70% of households took part online, by mail or on the phone, surpassing the rates of Texas and Florida.

“California did a good job of getting the count in and holding down the loss to one seat,” says Tony Quinn, a former Republican advisor on redistricting and editor of the Target Book, which monitors congressional and legislative races.

“It’s pretty clear Texas and Florida did not put in the resources to increase their census count. And they didn’t get as many seats as they might have. They anticipated getting three in Texas and two in Florida. If they’d put out a real effort, they would have.”

“In Republican states,” Quinn adds, “they didn’t understand that they’d be better off if they counted more people. They didn’t bother counting the undocumented and wound up on the short end of the stick.”

But redistricting in Texas and Florida will be strictly controlled by Republicans. So, the districts will be gerrymandered to greatly favor Republican candidates.

Democratic legislators used to do the same in California. But reform-minded voters ended gerrymandering by turning over the chore to an independent bipartisan commission.

California’s lost congressional seat is expected to be taken from Los Angeles County.

“L.A. is going to be the loser,” says Eric McGhee, a population and redistricting analyst at the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California. “L.A. has not been growing fast enough to keep up with other parts of the state. There’s going to be a [congressional] reshuffling there.”

So, why has California’s population growth slowed to a trickle?

Clearly, many people can’t afford to live here any longer because of high housing costs, a shortage of good, middle-class jobs and long commutes.

The strain of long commutes could be relieved by more people working at home, following the pandemic pattern.

The first batch of census data shows sluggish population growth, holds good news for the GOP and raises questions about a possible Latino undercount.

But business regulations are unwieldy. And there are perpetual gripes about high taxes. Texas, Florida and Nevada have no state income tax. California has by far the nation’s highest.

The Newsom administration fights back against such negative talk.

“There continue to be people with political axes to grind who want to put the hate on California,” says H.D. Palmer, spokesman for the state Finance Department.

“They don’t like the politics. Don’t like the culture. Don’t like the people.

“They try to inflate any data,” Palmer continues, “to fuel the feeling there’s an epic exodus that is jamming interstates out of California. The data does not bear that out.

“The reason the population growth has slowed is we are experiencing the effect of two national trends: a decline in the birth rate and reduced foreign immigration. Both of those have affected California to a greater extent than other regions of the country.”

OK, but still more people are moving to other states than are leaving other states to move to California. Actually, that has been happening for 30 years — under Republican and Democratic governorships.

“We’re not the boom state we once were,” McGhee says. “It’s too early to say if we’re on a down trajectory.”

But it’s not too early for a course correction to keep the rust off.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.