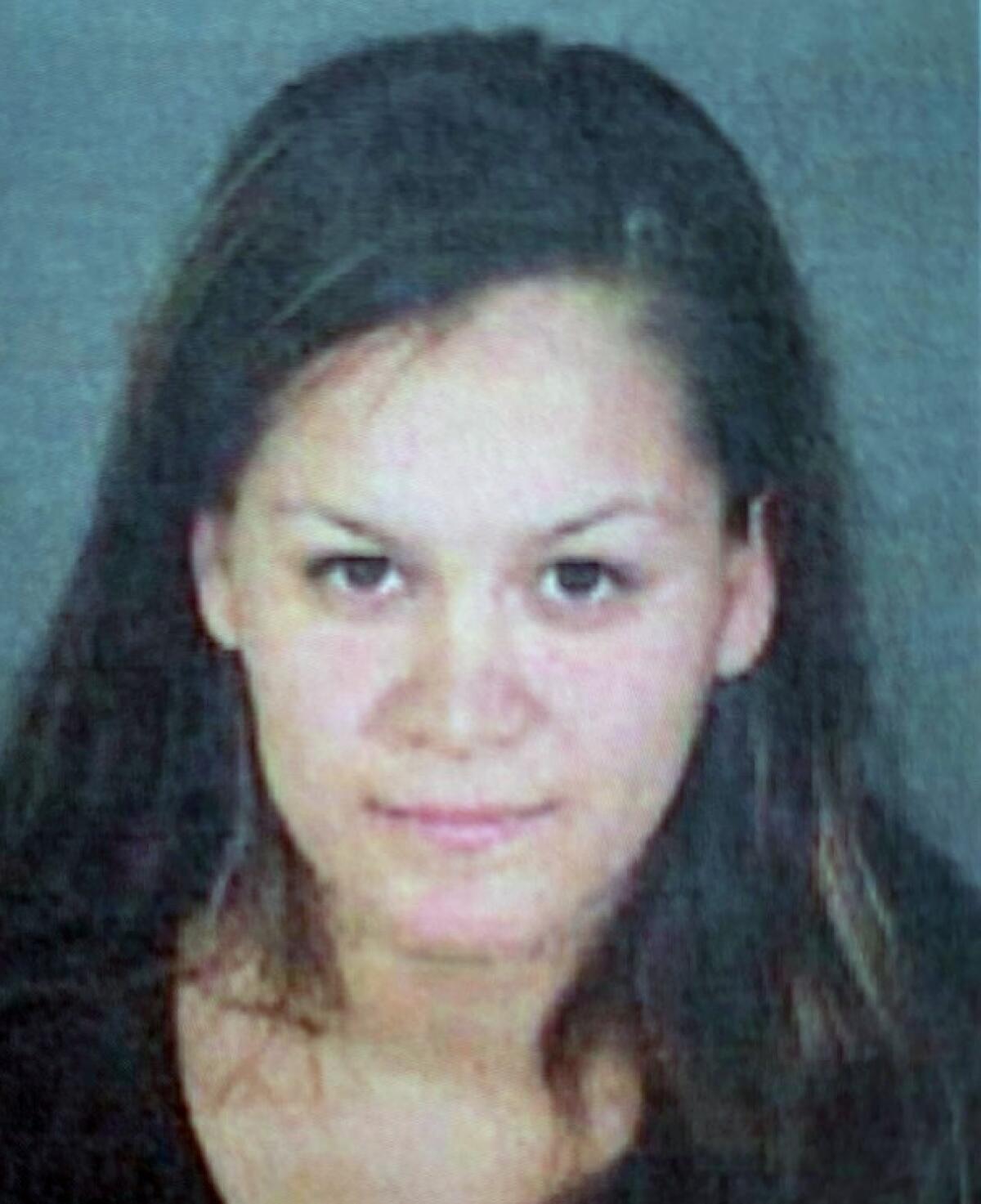

Mother unraveled in depression, QAnon-style conspiracies in months before she killed 3 kids

- Share via

Liliana Carrillo’s unraveling over the last year alarmed people in her life.

On Facebook, she spoke of “random invasive feelings of despair and pain.” She said she was “hating being a parent” to her brood of young children and wished she could go back in time.

“I have absolutely no patience or tolerance left,” she added.

More recently, she began to echo the delusion of QAnon believers. She was consumed by the idea that Porterville, Calif., was the site of a child sex-trafficking ring, according to court records, and contended that the blame for the pandemic rested on her shoulders.

It was clear she was struggling with postpartum depression, with anger, with childhood trauma and with the frustrations of young motherhood, her boyfriend, the father of her children, recounted in court records.

Last month, the situation got gravely worse. She started making wild allegations of child abuse, according to court records. Social workers and police in two counties got involved. The children’s father, Erik Denton, convinced a judge to award him physical custody of their three children, saying Carrillo was experiencing a psychotic episode and he feared for the kids’ well-being.

But Joanna, 3; Terry, 2; and Sierra, 6 months, remained with Carrillo.

Last weekend, a day before Denton said Carrillo was to turn the children over to him, her mother discovered the three grandchildren dead in the Reseda apartment they shared. In an extraordinary television interview from a Bakersfield jail on Thursday, Carrillo confessed to killing the kids, saying she was trying to protect them from sex trafficking.

“I drowned them,” she said, claiming she did so “softly.” She added, “I hugged them and I kissed them and I was apologizing the whole time.”

“Do I wish that I didn’t have to do that? Yes,” Carrillo said. “But I prefer them not being tortured and abused on a regular basis for the rest of their lives.”

Denton has roundly rejected any allegation that he abused or mistreated his children and has pointed to Carrillo’s mental instability. The killings followed weeks of pleas to child welfare agencies and police to get the three kids to safety, according to interviews, court records, Denton and his family’s notes documenting some interactions with authorities, and sources familiar with the ongoing investigation.

Her problems became known to two child welfare agencies and brought police from two different departments. But it was not enough to save the children.

Struggles with postpartum depression

The signs of postpartum depression in Carrillo emerged after she gave birth to the couple’s second child, their son Terry, in 2019, according to Denton’s account in court records.

By then, Denton and Carrillo — who met a few years earlier while she was driving for Uber and he was a passenger — had bounced around Van Nuys and Murrieta before settling down in the San Joaquin Valley city of Porterville.

For much of their relationship, Denton worked days-long stretches away from home while Carrillo cared for the children. Social media and text messages filed in court suggest the distance posed a strain on their relationship.

“Three more days and I’ll be home for good,” Denton said in a Facebook message. Carrillo replied, “Do you want to know how I feel? … I feel like we should have never had kids.”

She indicated in her message to Denton that she contemplated suicide “regularly” and that she feared she was exposing their toddler-age daughter to her mental health issues.

Carrillo complained about her daughter not listening, along with the unending, mundane chores of managing a household and rearing children, often in rambling, expletive-filled Facebook status updates.

“I fight feelings of leaving all the f— time now when left alone with them,” she posted.

Denton also tired of being away from his family, according to the messages, and wrote to Carrillo in the fall of 2019, “I don’t want to give up and you 3 are the only things keeping me from giving up.” Carrillo responded that she would begin working so he could return to live permanently with his kids.

“You have done marvelously. It’s time for you to rest,” she told him.

Denton became a stay-at-home parent at the end of 2019, while Carrillo began taking on temporary work outside the home.

During this time, he said in court papers, Carrillo’s depression worsened. Although she started therapy, she abruptly quit and refused psychiatric medications, instead turning to marijuana. In 2020, while pregnant with their third child, Carrillo indicated in a text message to Denton that she was “on the verge of so many emotions at once” and thus was going to smoke some pot.

After giving birth to Sierra in October, Denton said, Carrillo’s mental state frayed further.

“Her condition has worsened; she is not taking care of herself and has lost touch with reality,” he said in a declaration filed in court, listing her impulsive behavior, such as a fixation on the idea that those around her in Porterville were engaging in pedophilia and sex abuse.

An incident at a Porterville park appeared to catalyze Carrillo in an intense way. In mid-February, their eldest daughter, Joanna, fell and hit her groin at a playground. Although Carrillo witnessed it, and afterward Denton said their daughter “was acting normally without complaint,” Carrillo accused Denton of “being a part of a pedophile ring” and allowing someone to molest their daughter.

A visit to Valley Presbyterian Hospital three days later resulted in a physician not identifying “any concerning signs or symptoms” in Joanna, according to medical records provided to The Times.

Fixation on claims of molestation

But Carrillo appeared fixated on her claims of molestation, and alternated between apologizing to Denton and stating she could not stop thinking the sex abuse was real.

On Feb. 25, Carrillo again took her eldest child to a hospital, this time to Sequoia Family Medical Center in Porterville. There, she reported irritation in her daughter’s genitals that she claimed resulted from abuse, according to medical records in a dossier Carrillo later released. The staffer wrote in records that as a mandated reporter, she had to notify Tulare County social services, and she documented contacting social workers and sharing “pertinent information” on both Carrillo and Denton along with “concerns for drug exposure.”

That night, Carrillo attempted to leave with her children. Denton said he tried to stop her and contacted the city’s Police Department. Police later wrote that Carrillo was “acting strange and trying to take their children to Los Angeles” and that Denton “is concerned,” according to records of the calls for service reviewed by The Times.

But in a pattern that played out over the next troubling few weeks, Carrillo also called police and lobbed allegations of exploitation: “She thinks that the children are being abused,” police wrote, according to records of the call.

Within a day, Carrillo’s mother had driven from L.A. and picked up her daughter and grandchildren. Carrillo took the children’s legal documents, told Denton she “could go to Mexico,” where she has family, and for days afterward, refused to share their whereabouts, according to court records from the custody case.

A Tulare County social worker contacted Denton the next day after speaking with Carrillo. The social worker, he said, was “concerned about her mental state” as Carrillo had accused the social worker of not being legitimate and also refused to disclose where she or the children were. The social worker then instructed Denton on how to petition a court to intervene.

Denton secured an emergency court order for the children’s custody in March, and the judge required that any visits between Carrillo and the children be supervised at a special facility in Porterville.

Dr. Teri Miller, an emergency room physician who assisted her cousin, Denton, with trying to save the children, said that she and Denton went to the L.A. County Department of Children and Family Services as well as the LAPD to notify the agencies that Carrillo had psychosis, had taken the children and was essentially hiding in L.A.

Records indicate that an L.A. County social worker tried to visit Carrillo on March 4, leaving a note that said they needed to discuss “a child abuse report we have received in regards to your children.” The social worker left her cellphone number and said she planned to return March 9.

Pleas to protect the children

Carrillo received the order giving Denton physical custody around March 12, according to records, and afterward, she went to the Los Angeles Police Department’s West Valley station, where Denton had requested she hand over the children. There, an officer notified her of the consequences of failing to abide by the court order, according to a summary of the meeting Denton provided in court. Carrillo apparently opted to disregard the order.

After discovering Carrillo’s whereabouts, Denton and Miller said they also called the LAPD and begged police to take her to a mental health facility for psychiatric evaluation. Both told police that Carrillo was a danger to the children and herself.

Miller said that two officers met them at a parking lot at one point to discuss Carrillo’s mental health, and that officers even called a supervisor to the scene.

“I told them she might kill the kids,” Miller recalled.

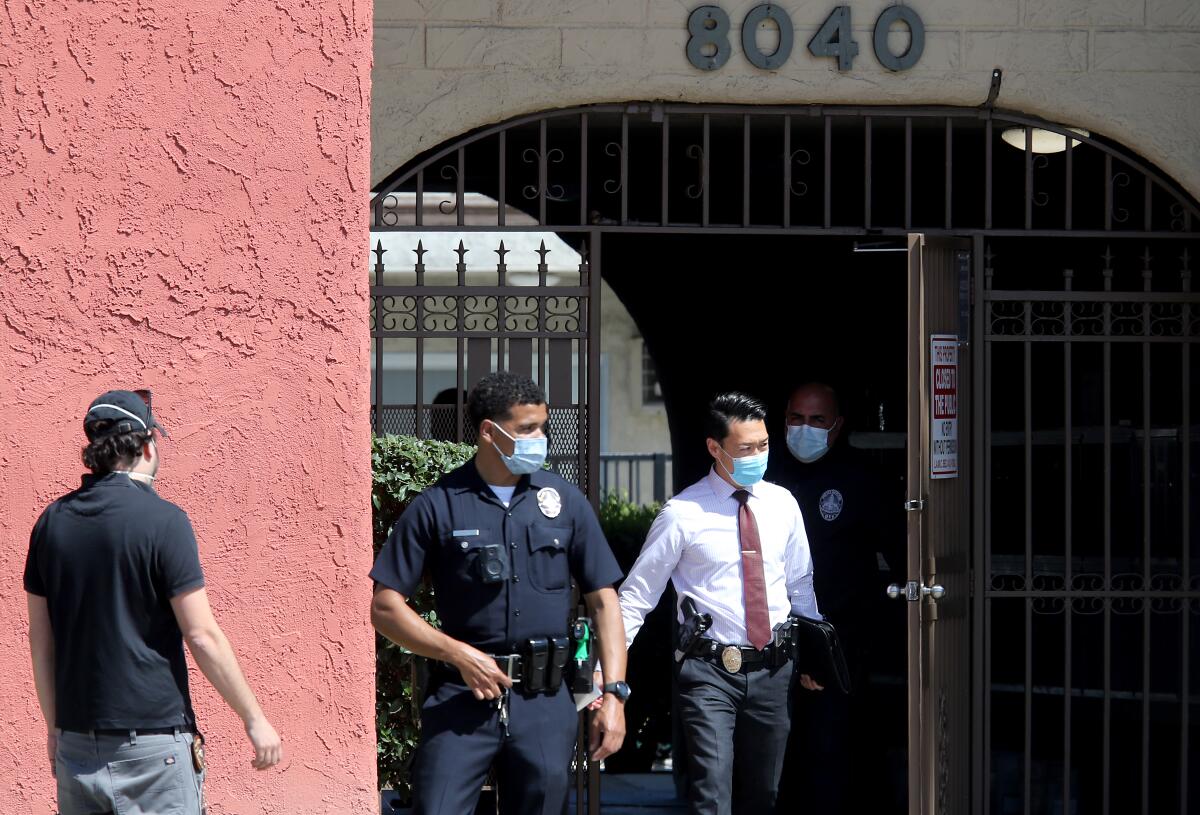

LAPD’s internal affairs unit has since launched an investigation into how West Valley officers handled the reports regarding Carrillo, as well as the officers’ interactions with Miller and Denton.

Miller and Denton said they had conversations with L.A. County’s child welfare agency in which they both stated that Carrillo should not be alone with the children. “I spoke to the social worker for like 2½ hours, and she told me, ‘I don’t believe Liliana will harm the children,’” Denton said. His contemporaneous notes indicate the conversation was on March 19.

“She was incredibly sick,” Miller said of Carrillo. The physician opined that if the mother had showed up to the emergency room in such a mental state, she would have been held for evaluation. She questioned how the LAPD and the county DCFS could defend their handling of the case.

“They’re afraid to take action and make decisions,” she said.

Authorities further became aware of problems with the family around early April, when Carrillo sought a temporary restraining order against Denton and accused him of sexually abusing their eldest daughter, according to court records. Denton denied the allegation. Carrillo also made the abuse allegation directly to L.A. County DCFS, according to Miller, who said social workers had not yet performed a formal interview with Denton about the claim.

A final manifesto

In the very early morning hours of April 10, Carrillo tapped out a message to an unnamed judge along with several media outlets.

She wrote that she was “by my children’s side since they were born,” referenced her postpartum depression, and proceeded to offer a manifesto.

“I don’t know when I became a target, but I know that Porterville is the root of all evil right now. Both of my children have now vocalized to me more than once that their private parts hurt,” she said. She positioned herself as protecting the kids.

In a lengthy email that included an attachment with more than 100 pages of typed and handwritten notes and images, she offered a meandering and at times incoherent account of a young, unstable mother. She attached screenshots of text messages, medical records and annotated court records.

“I am removing myself and my children from this world because nothing will ever be the same. There is no going back from here,” she wrote.

Hours later, Carrillo’s mother discovered the three slain children in the apartment in Reseda. Around 11 a.m., a pickup truck driver came upon Carrillo along Highway 65, just north of Bakersfield. The black Ford Focus that Carrillo had driven was stuck near the shoulder. At first one driver stopped, then another.

One of the drivers later recalled that Carrillo had a cut that looked “meaty,” and he feared she was suicidal and might throw herself into oncoming traffic. She appeared agitated and distraught, he told police, and when farmworkers stopped to give her water, she swatted the bottles away.

One driver tried to calm her down and told her they had called 911 for help.

“I’m being trafficked, you don’t understand, I need to go,” she told the driver, according to a police report of the incident.

She then tried to drive away in a Ford F-150 belonging to one of the drivers. The pickup truck’s owner managed to pull her out of the vehicle, and she later got into another driver’s silver Toyota Tacoma. That truck did not have its keys, but when the Tacoma’s owner ran over to get her out, it allowed Carrillo to turn on the keyless

ignition and drive off, police wrote in records. She was barefoot, having left behind some black sandals.

Authorities were concerned since the Tacoma’s driver had left four guns and 1,000 rounds of ammunition in the truck, saying he was en route to a shooting range.

Later that afternoon, Carrillo was found driving the Tacoma and was ultimately arrested by Tulare County authorities near Ponderosa, hospitalized, then transferred south.

‘I love you, and I’m sorry’

Los Angeles County prosecutors have not filed charges against Carrillo. She remains in custody in a Kern County jail in lieu of $2-million bond on charges related to carjacking and auto theft. “I know that I’m going to be in jail for the rest of my life,” she told the reporter with KGET-TV, an NBC affiliate in Bakersfield, while sitting shackled.

“What was the final message to your children?” the reporter inquired.

Carrillo recalled telling them, “I love you, and I’m sorry.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.