UC Riverside has high share of underserved students. But funding gap prompts equity debate

- Share via

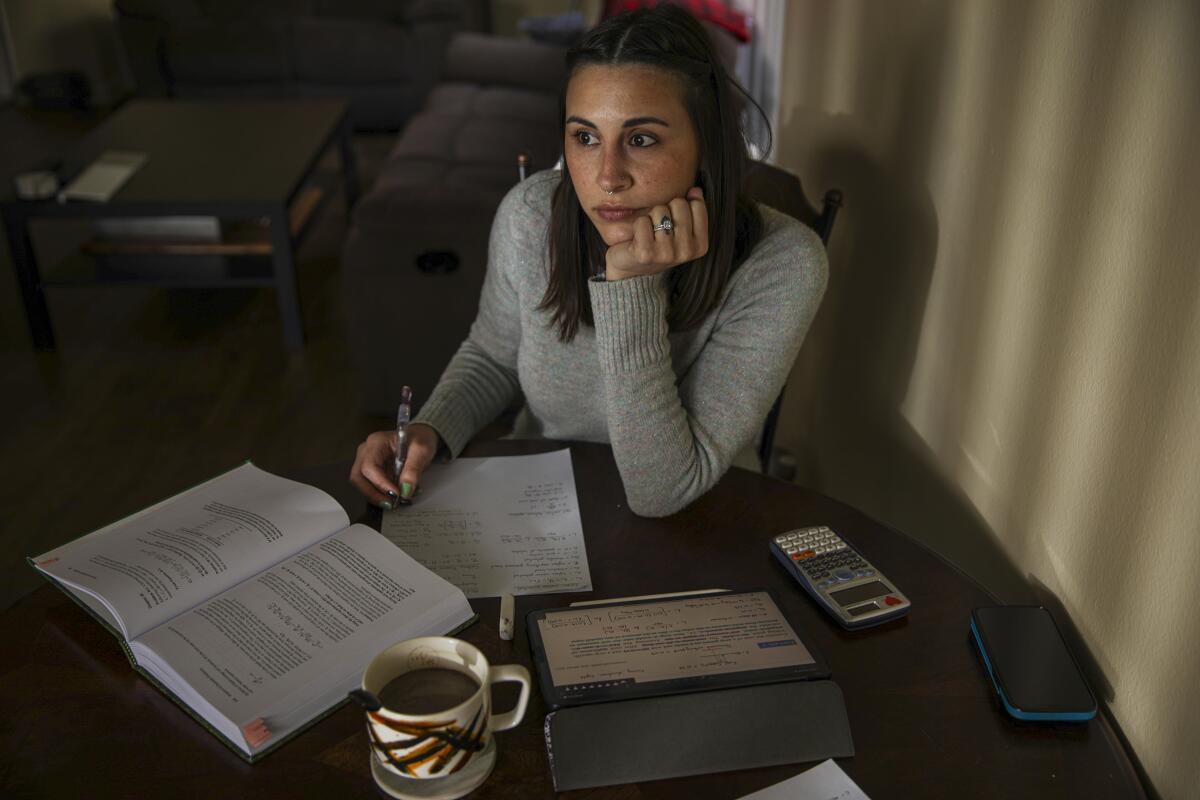

Casaundra Caruso was nearly a straight-A student when she transferred from San Bernardino Valley College to UC Riverside in fall 2019. But that quickly — and disastrously — changed.

She was overwhelmed by UC Riverside’s fast-paced quarter system and flummoxed by the process of transferring her credits to Riverside. She didn’t know how to seek campus help and, as the first in her family to attend college, couldn’t ask her parents.

She failed a class for the first time ever and her first-quarter grades plunged to a 2.8 GPA.

“It was miserable,” Caruso said. “You’re basically thrown into it. I would have had a better experience if UCR had more staff and resources.”

Although the University of California considers itself one system, its 286,000 students do not have access to equal resources and services across its 10 campuses. Among them, UC Riverside students fall far behind their peers when it comes to receiving essential services — transfer student support, counseling, academic advising.

Many Riverside facilities are in deep disrepair. Students have endured falling ceiling tiles, leaking roofs, antiquated air systems that emit mold and lab equipment breakdowns. Staff morale has been low and turnover high. Faculty research has been compromised by dysfunctional facilities and airborne contamination.

Yet the Inland Empire campus educates a larger share of needy students — about half are low-income, underrepresented minorities or the first in their families to attend college — than all other campuses except for UC Merced, which is funded at higher levels because of its small size.

The disparities are igniting alarm and allegations by Riverside supporters of de facto racism against the campus. Troubled regents are calling for a closer look at the inequities. State Assemblyman Jose Medina (D-Riverside) has asked UC President Michael V. Drake to address the problems.

“This pattern of systemic neglect and chronic underfunding of a university serving a student body composed of at least 85% students of color is troublingly reminiscent of redlining,” several UC Riverside department chairs said in a recent letter to Drake and the Board of Regents.

The concerns have prompted UC to launch a new evaluation of how to allocate taxpayer-supported state funding to campuses, the first such review in a decade. But UC finances are complex and the politics thorny, touching on the combustible issues of equity and privilege, class and race.

The impact on UC campuses is potentially huge. Should state dollars be taken from UCLA, UC Berkeley and UC San Diego — which raise billions in private fundraising and reap millions in extra revenue from nonresident student tuition — for smaller, struggling campuses with more disadvantaged students like Riverside and Merced? Should every campus stand on its own?

“It’s obviously delicate because reallocating funding amongst the campuses means inevitably that there are going to be winners and there are going to be losers,” said George Blumenthal, the former UC Santa Cruz chancellor who began lobbying in 2006 to reallocate state funds when he learned his campus was receiving substantially less per student than older campuses like UCLA.

Any solutions are bound to be highly contested. Ideas include sharing the extra tuition that nonresident students pay — which would take the most from UCLA, Berkeley and San Diego — or pegging funding to the number of disadvantaged students enrolled, which would most benefit Riverside, Merced and Irvine.

Nathan Brostrom, UC chief financial officer, said his office is modeling different approaches for Drake, including a needs-based element. “We are firmly committed to a transparent and equitable way to allocate state resources across the system,” Brostrom said.

He added that all UC campuses are facing financial challenges since they’ve added more than 110,000 students over the last two decades without receiving enough state funding to cover their full cost of instruction. And the pandemic has deepened the pain — opening a $340-million deficit at Berkeley, for instance.

As the pandemic throws University of California campuses into financial crisis, some chancellors say it’s time to begin talking about a tuition increase.

But the funding issue has ignited a furor at Riverside. Chancellor Kim Wilcox recently told regents that the campus was considering axing its entire athletic program and curtailing student programs in Washington, D.C., Sacramento and abroad. Stipends for undergraduate research have been cut off.

“We can’t just quietly accept this level of inequity,” said Melissa M. Wilcox, chair of the religious studies department who helped craft the faculty letter, which has garnered more than 1,200 signatures of support on Change.org. “Our students deserve to have us fight for them.”

Caruso, the transfer student, experienced the fallout from staffing shortages. UC Riverside has only one full-time staff member to serve 5,220 transfer students — the highest workload among UC campuses. By comparison, UC Irvine has nine people — five staffers and four student workers — for 6,655 transfer students. UC Berkeley has five staff members and 28 student workers for 6,334 transfer students.

Riverside counselors each juggle an average of 1,958 students, nearly twice as large as the UC system target — and Riverside has fewer academic advisors, psychiatrists, faculty and staff overall than the system average. To achieve parity, Riverside would need to hire 760 more staff members to meet the systemwide average student-to-staff ratio of 5.6 to 1, according to the campus’ analysis.

“I’m still paying the same UC tuition as everyone else but don’t have the same advantages and it’s not fair,” Caruso said.

Amid calls for greater equity, UC adopted a new funding formula in 2012 and equalized per-student allocations four years later. Campuses receive $35,600 per health sciences student, $17,800 for each academic doctoral student and $7,100 for each undergraduate — differences based on the cost of instruction for each category of students, a calculation generally derived from faculty-to-student ratios.

But because Riverside educates fewer doctoral and health sciences students, it receives less enrollment funding overall. Those allocations, spread out among all students regardless of category, amount to about $8,600 per person at Riverside compared with $11,500 at UCLA and about $10,000 at Berkeley, Davis, Irvine and San Diego.

What’s more, the campus hasn’t been able to supplement state funding with lucrative income from private philanthropy, nonresident student tuition or medical centers anywhere near the level of UCLA or UC San Diego, for instance.

Riverside raised $313 million in its last capital campaign, compared with $5.5 billion for UCLA and $4.3 billion so far in Berkeley’s current campaign. The Inland Empire campus reaped extra nonresident tuition revenue from only about 2,200 students compared with 10,200 for San Diego and 10,500 for UCLA.

UCLA has raised $5.49 billion in one of the nation’s most successful public university fundraising campaigns, which comes amid a decline in state support.

“All those things together provide a different environment for some students in the university than others, depending on which campus they’re enrolled in,” said Wilcox, the Riverside chancellor. “We’re one university and students should have comparable experiences.”

UC officials say, however, that the funding picture is complex.

UC Riverside actually ranks fifth among 10 campuses in total state general funding received, they said, because its enrollment funds are supplemented by an additional $84 million allocated to its medical school, agricultural research, student outreach, basic needs and other programs.

Riverside officials, however, said they can’t use those special funds as flexibly as they can with enrollment money — which is primarily used for education, research and student support — so the description is misleading. Money earmarked for the medical school, for instance, can’t be used to beef up transfer student support.

Recognizing the disparities, the 10 chancellors and then-President Janet Napolitano last year agreed to give a greater share of new state funding over the next three years to campuses with fewer health sciences and doctoral students: Riverside, along with Santa Barbara and Santa Cruz.

UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ said she joined the consensus to make that change even though her campus would not benefit. But she said any further revamping should recognize that higher-cost doctoral education appropriately receives more funding. She added that she dislikes the “caricature” of some campuses serving privileged students and others, disadvantaged ones, noting that Berkeley also enrolls many low-income and first-generation students.

UCLA could be the biggest loser under any new formula. Chancellor Gene Block declined to talk about the issue.

Critics of the current system, however, are pushing hard for change. No one is advocating that private philanthropy be divvied up among campuses, since donors specify their gift recipients. But Medina and other experts have called for the $1.2 billion in supplemental nonresident tuition annually collected by UC campuses to be shared or “taxed” — a portion going into a pool to be redistributed. Blumenthal said a tax would be justified because regents placed an 18% cap on out-of-state undergraduate students in 2017 — but allowed UCLA, Berkeley, San Diego and Irvine to grandfather in their existing limits, which were as high as 24%.

UC Merced and UC Riverside serve more racially marginalized students than other campuses and yet have far fewer resources to do that job.

Others say UC should rethink whether to continue allocating five times as much funding for all health sciences students as undergraduates.

UC Riverside Vice Provost Jennifer Brown said UC formulas should recognize that disadvantaged students need more support — as the state does in giving extra K-12 funds for students who are low-income, learning English or in foster care. Riverside has won national accolades for successfully educating underrepresented minorities with virtually no racial achievement gap. Still, the six-year graduation rate of 79.6% is lower than all campuses but Merced and Santa Cruz.

The issue has headed to the regents, several of whom have spoken out about the need to review the funding formula. “If it really is our goal to ... create more equity for our students, we do have to really look at the campuses that are serving the highest proportion of [low income], underrepresented, historically marginalized students,” Regent Lark Park said at a January board meeting.

At Riverside, the stories of need are stark.

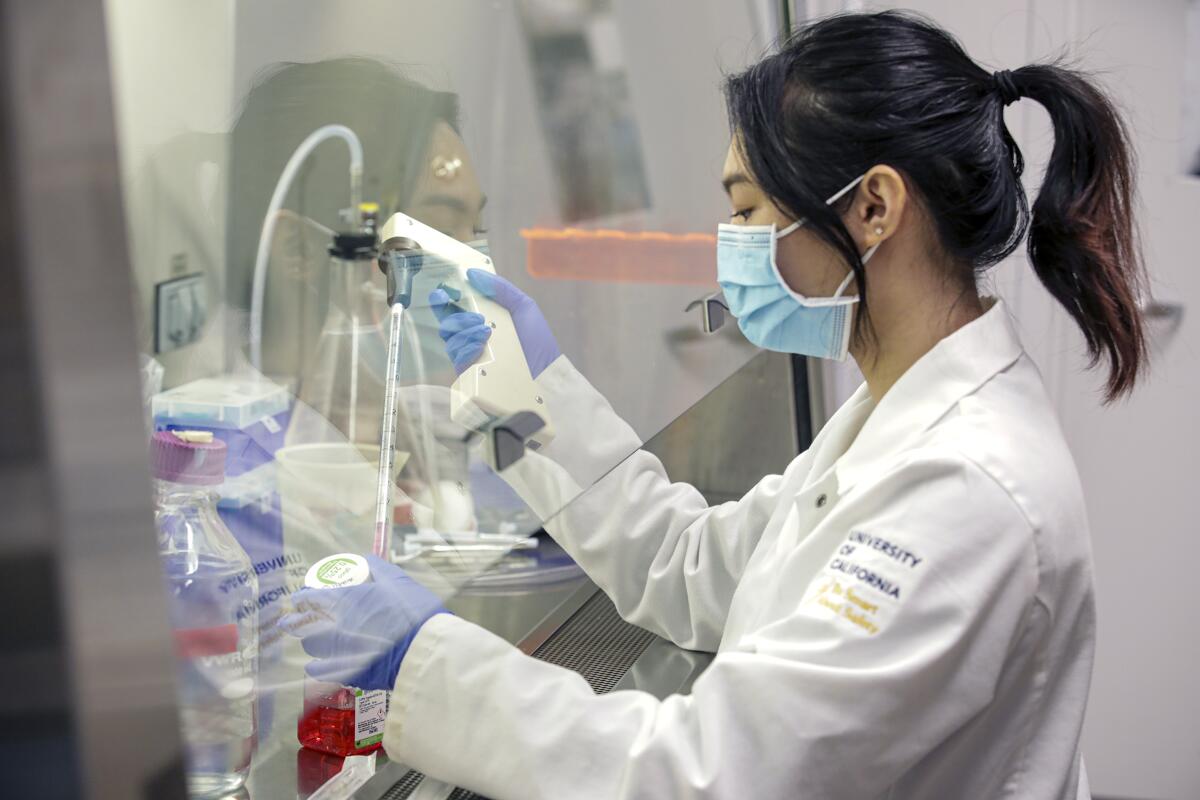

Robert Jinkerson, an assistant professor of chemical and environmental engineering, says his students cannot fully complete hands-on experiments to learn distillation and other chemical operations because of overcrowded classes and aging equipment that frequently breaks down. He has to divide up his students, who take turns doing the experiments and just watching them.

“It becomes a logistical disaster,” Jinkerson said. “And it has a huge impact. If students don’t have hands-on experience ... they won’t be as sought after for jobs.”

Helen Regan, a biology professor, has led numerous “disaster tours,” as she calls them, to show legislators and UC officials the state of campus disrepair — including ceiling tiles that collapsed in a classroom where students were taking a final exam. Water leaks have caused the campus to cancel labs and tape down warped floor tiles that rise and expose asbestos.

Faculty research is compromised by the relative lack of state-of-the art microscopes and equipment. In one 2013 disaster, a multimillion-dollar research project was destroyed when a greenhouse overheated during a summer power failure, decimating insect and nematode cultures.

Riverside has lost several leading faculty members and top graduate student prospects to other institutions with better facilities and higher pay, said Jernej Murn, an assistant professor of biochemistry.

And staff are stretched so thin that many are doing two jobs at once. Academic advisors in the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences have workloads nearly twice as high as the 300:1 student/advisor ratio recommended for the underserved students Riverside enrolls.

“Folks are resilient and want to stay, but it’s taking a toll on their mental and emotional health,” said Crystal Petrini, a campus financial and administrative manager who heads the systemwide Council of UC Staff Assemblies.

For students, the disparities are demoralizing. Yvonne Marquéz wants a physical space and more programming for student parents like herself, as UCLA offers. Kiki Chavez would love to have COVID-19 tests available in vending machines, as UC San Diego supplies. Deidre Reyes would like more disability services while Jennifer Le hopes that undergraduate research grants will be restored.

Caruso, who has worked her way back up to a 3.4 GPA, said more academic advisors and counselors would help protect students from disastrous experiences like hers.

“With more funding, students will have more opportunities to research, grow and achieve,” said Marquéz, a senior in history who overcame the challenges of poverty, homelessness and single parenting to marry and return to school at age 32 four years ago. “We owe it to the community to do better.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.