In California, a million English learners are at risk of intractable education loss

- Share via

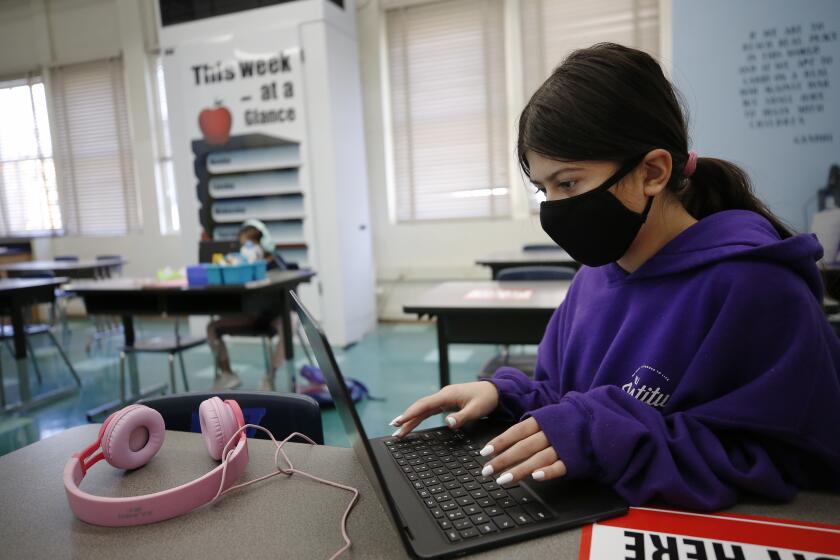

Aida Vega’s 13-year-old daughter, who has attended Los Angeles schools since kindergarten and is in eighth grade, still struggles to read and write English.

Vega has long pushed for extra help so her child can master the language. Early last year, she felt confident that a breakthrough was at hand — her daughter’s teachers had a plan to start additional tutoring in March.

Then schools closed. Tutoring was canceled, except for a short stint during the fall semester. Vega says her daughter’s schooling became a constant struggle. There are days when Vega has found her in tears next to her computer. In the fall, after teachers said her daughter was failing all of her classes, Vega began taking jobs cleaning homes and offices to pay $45 an hour for a private tutor. But she worries her daughter is still falling behind.

“It’s tough to see the light,” Vega said. “The impact of this time is going to be big. It’s going to be bad.”

More than 1.1 million students in California, nearly 20%, are considered English learners. By almost every measure of academic success — graduation rates, college preparation, dropout rates, state standards — these students rank among the lowest-achieving groups. And that was before pandemic-forced campus closures. One year later, this massive population of students is at great risk of intractable educational loss, experts said.

“It’s an educational pandemic,” said Martha Hernandez, director of Californians Together, a nonprofit that advocates for English learners. “We already had issues of an achievement gap, opportunity gaps, lack of access, lack of equity. Now that’s just exacerbated, and it will be a huge challenge. It will have a big impact for many, many years.”

Más de 1.1 millones de estudiantes en California son considerados estudiantes de inglés y los expertos dicen que las escuelas deben hacer intervenciones inmediatas y rápidas para salvar la educación.

She and other experts, parents and educators say schools must make immediate and swift interventions to salvage the education of English learners — 80% of whom speak Spanish — including improving distance learning for those families that choose to continue online and extending the school year and school days to allow for additional learning time.

An abundance of reports in California and throughout the country show the dire toll distance learning has taken on these students.

The Los Angeles Unified School District educates about 120,000 English learners, or 20% of its students, and reported that in spring 2020 fewer than half of English learners in middle and high school participated in distance learning each week — a gap of about 20 percentage points compared to students who are proficient in English.

Last month, the district reported that 42% of grades earned by English learners in high school were Ds and Fs, an increase of 10 percentage points from the prior year — greater than any other group except homeless youth. Middle schoolers saw a 12 percentage point increase in Ds and Fs.

And fall interim assessment results indicate that more than 94% of the district’s English learners in middle and high school were not on grade level in reading and math, according to a report this week by the advocacy group Great Public Schools Now, based on district data.

CapRadio reported in June that of the more than 500 Sacramento City Unified students who stopped attending school after campuses shuttered, about 44% were English learners. The drop in participation is in contrast to pre-pandemic times, when they were less likely than others to be chronically absent, according to a report by the nonpartisan research group Migration Policy Institute.

Fairfax County Public Schools in Virginia, one of the nation’s largest public school districts, reported that the percentage of English learners earning more than two failing grades more than doubled, to 35%. The district also found that English learners’ performance in math and English had dropped far more than that of any other group — with 47% underperforming in math and 53% underperforming in English.

The greatest academic harm fell on younger students and those who were faring worse before the pandemic, the report said.

Pre-pandemic learning

Long before the pandemic, English learners faced significant barriers to their education. Historically, they have been met with low expectations, inadequate resources and decision-making mired in the politics of immigration.

For nearly two decades, California operated under rules approved by voters in 1998, which sought to minimize bilingual education in favor of English-only instruction, under the argument that it failed to assimilate students and wasted financial resources. Nearly two decades later, in 2016, voters overturned those rules, giving schools more flexibility to offer academic programs that incorporate the use of a student’s native language.

But the legacy of fractured policymaking continues to affect the education of English learners, the majority of whom are from low-income families. In addition to Spanish, they speak Vietnamese, Mandarin and Arabic, among dozens of other languages. The vast majority were born in the U.S.

In California, the graduation rate for English learners in 2020 was about 69%, compared with 84% overall, reflecting a gap that has persisted for years.

How the pandemic created even more barriers

Francisco Lozano, the father of an English learner in fifth grade in Santa Maria, has worked for years to help organize and train Mixteco- and Spanish-speaking parents, to help them understand the educational system so they can better advocate for their children.

But even as a parent organizer, Lozano said, he struggled to help his daughter when schools closed. She was given a tablet, but he needed help understanding how to get her logged into class. He tried calling the school while on breaks from his work as a gardener. Nearly three weeks passed before she was able to join her virtual classroom.

“I was working and trying to call the technicians for help, and we couldn’t get into her class,” he said. “I felt a lot of frustration.”

These days, Lozano said, the parents he works with frequently tell him their children are struggling, and they don’t know how to help. The Santa Maria-Bonita School District plans to start bringing students in some elementary grades back to campus in mid-April.

“Our kids were already behind,” Lozano said. “But now? If the districts and the schools don’t start doing what they need to do, we’ll all be left behind.”

Patricia Gandara, a professor of education at UCLA and an expert on English learners, said she fears students will be so discouraged they drop out altogether.

“All along we have argued that English learners need additional time under normal circumstances, because they’re being asked to do much more than the typical kid who speaks English,” she said. “They’re chronically short on instructional time, and this has exacerbated this so much that I worry ... that they’re so far behind and they can’t catch up, and they just give up.”

Myriad challenges result from circumstances outside of school: Latino and immigrant families have been devastated during the pandemic, both economically and by the virus. Many older students have had to take care of siblings, take jobs or find ways to learn in crowded homes.

‘My parents’ worries became my own.’ L.A. students have taken on grueling work to support their families during the pandemic.

But virtual classrooms also pose unique challenges for English learners, making it difficult for teachers to use techniques like small groups and visual cues that help language learners, who are working to understand the subject and the language at the same time. Teachers often cover their walls with images and words to help reinforce the language.

“When you’re teaching kids who are already proficient in English, you’re focusing on the content,” said Alison Bailey, a professor of education at UCLA who studies language acquisition in children. “With an English-language learner you have to think, are they struggling with the math right now or have I not made that math content accessible to them in the language?”

School districts also found there were almost no distance learning resources for English learners.

Lydia Acosta Stephens, executive director for the Multilingual and Multicultural Education Department at Los Angeles Unified, said the district created a booklet of at-home activities that was mailed to English learners. Families were encouraged to prod language development with activities like an indoor treasure hunt for younger students, a reading log and journal and question prompts to encourage conversation. The district also purchased Rosetta Stone language learning software for students.

“Language is community, it’s engaging in those classrooms environments,” she said. “Virtually, we’re doing it. But there’s a different sense when we’re all in the same place.”

Learning a language in isolation

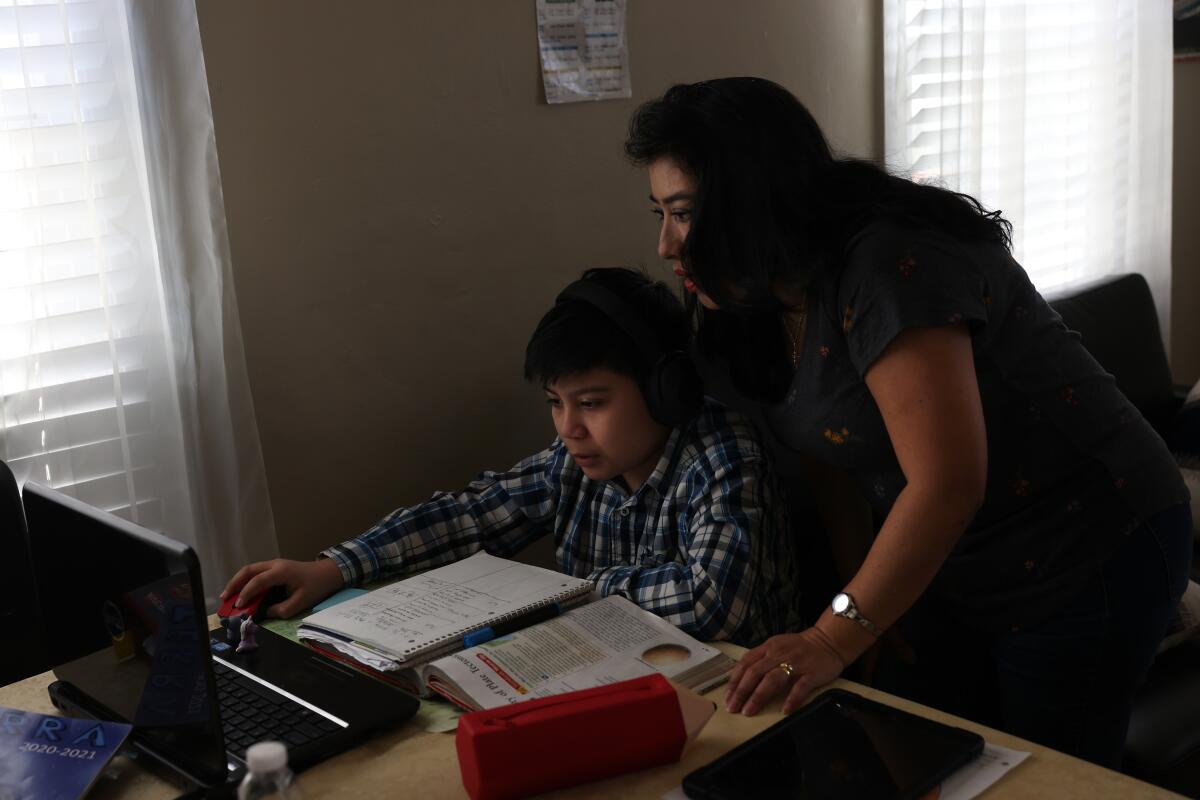

Jose Pozo arrived in Lake Elsinore from Ecuador nearly three years ago, having won a visa lottery and hoping that his sons would find opportunity in the U.S.

His youngest son, Esteban, who is in sixth grade, struggled with English at first. But it got easier as he made friends and played soccer. The pandemic left him feeling detached. He’s a diligent student who wins awards from his teachers. But when he was asked to speak English for a recent assessment, he told his parents it filled him with fear.

“He tells us that he does interact with his teachers, but it’s not the same as the day-to-day practice he used to get,” Pozo said. “Before, he was advancing very quickly. ... Now his English ability has gone down.”

The forced isolation has stripped English learners of important opportunities to practice the language, like they would in everyday conversations on the playground, at lunch and in the classroom.

Even as schools reopen throughout the state, they are often doing so with limited schedules. In many Latino and immigrant communities that have experienced the worst toll of the virus, parents are showing a reluctance to send students back to campus.

In L.A. Unified, which is preparing to reopen some campuses in mid-April, only about 40% of parents in the the heavily immigrant and Latino communities of Boyle Heights, MacArthur Park, South Central and Pico-Union opted to return their children to campus, according to survey results released in March, compared with West L.A., where 82% were choosing to return.

Diana Guillen, the chair of the District English Learner Advisory Committee, created to engage parents of English learners in educational decisions, said school leaders have left parents out of the loop, which is especially harmful at a time when parents are shouldering more responsibility for their children’s education.

“We have many parents who don’t know how to read or write, or speak another [indigenous] language,” she said. “They need support.” Instead, she said, parents of English learners often feel as if their voices are squashed.

The district says it has worked to support parents and provide additional support to English learners during and after school, including tutoring. About 4,500 English-learners receive tutoring from the district, said spokeswoman Barbara Jones — about 3.75% of the total.

A school district tries to make it work

At Compton Unified, educators said they felt an urgency to bring English learners and other vulnerable students back into the classroom.

“It was truly our moral imperative to ensure that those students who are being most affected are being provided the support and services to help them,” said Jennifer Graziano, director of English learner services at Compton Unified.

In mid-October, the district began bringing some students considered especially at risk back to school. The decision was controversial — with many teachers saying the district had not taken sufficient steps to ensure safety. District officials said they have taken extensive safety measures.

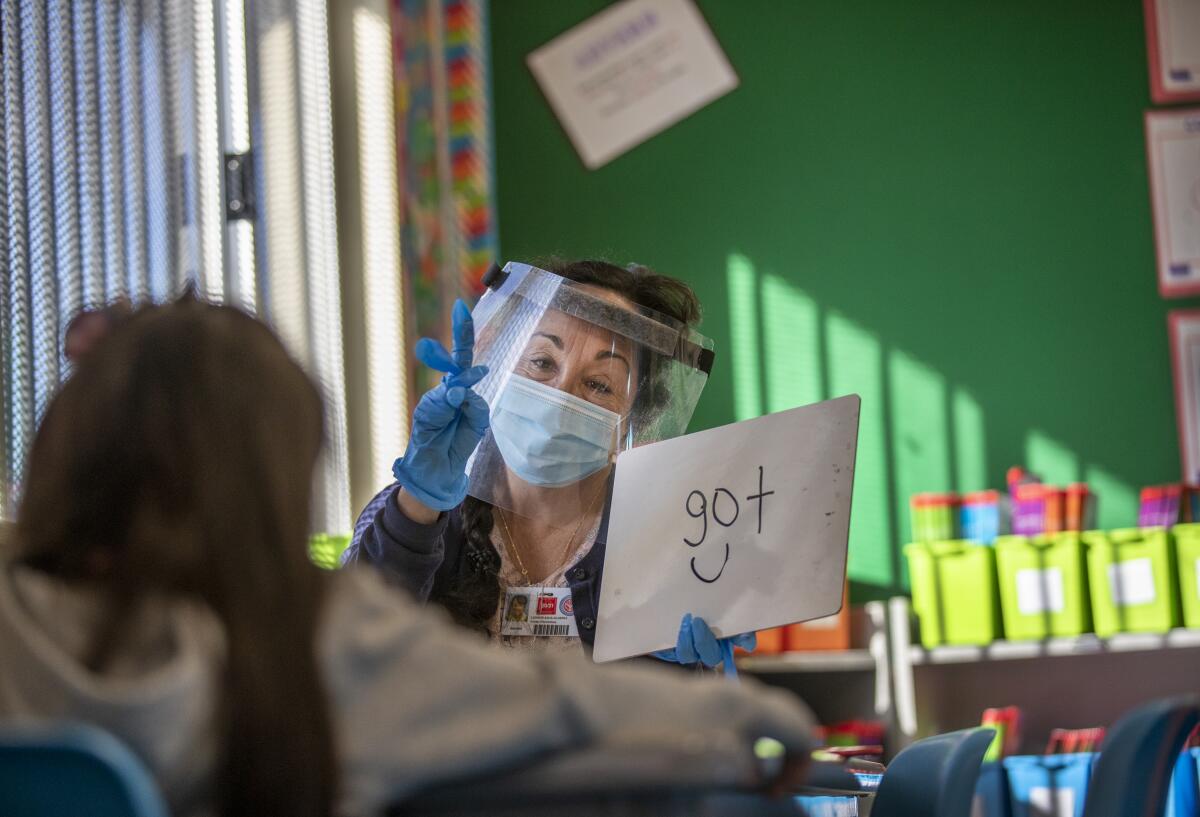

The district welcomed 379 English learners back to the classroom — out of about 6,100 in the district — with teachers simultaneously instructing them and their peers online at home. They targeted long-term English learners, newcomer students and the youngest students, who are learning to read, Graziano said.

On a weekday in the fall at Foster Elementary School, where more than one-third of students are English learners, first-grade teacher Rebecca Wilson asked her students to point at the words in their books as they read aloud together.

“Th-is i-i-s the t-t-town o-on a m-m-ap,” she said, drawing out the first sound of each word.

In the back of the room, a teacher’s aide wearing a face shield, sat across from a girl, holding a small white board. She wrote letters on the board and asked the girl to sound them out.

S. “What sound does it make?”

“Sss” the girl replied. She did the same for the letters O and CK.

Then she wrote the letters together. “Now blend it,” she told the girl.

“Sock,” the girl said.

“You got it!” the teacher’s aide said, giving a thumbs-up.

Everything happening in the classroom — the slow, deliberate reading, the one-on-one work, the oversized vowels on posters at the front of the room — was meant to set a foundation for strong reading.

In early March, the district more fully reopened elementary schools. About 50 English learners returned to 450-student Foster Elementary, said Principal Maria Alejandra Monroy. In total, about 90 K-5 students are on campus on a typical day. The reasons parents have for keeping children home are complicated: schedules, transportation, fear.

“There are some families that have lost parents and grandmas and aunties,” she said.

As students slowly return, Monroy said, it’s clear English learners are struggling. Many second-graders, for example, are lacking the reading skills they normally would have developed toward the end of the year in first grade. They need intensive, targeted intervention, which the school is offering before and after school and which will continue in the summer and fall, Monroy said.

“Let’s face reality, this is what we have,” Monroy said. “Now, how can we make it better? How can we change what didn’t happen because of the pandemic?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.