Column: A week later, here’s what happened to some of the homeless people booted from Echo Park

- Share via

Olga was flustered when she answered the phone.

“I need to call you back. They are telling me I need to leave.”

A week ago, Olga was living in a tent along Echo Park Lake. I’d reached her at the hotel to which she had been relocated after being ousted from the park — along with roughly 200 other homeless people who had built a commune-like encampment that, depending on whom you ask, was either a safe space or a haven for criminals.

When it became clear that city officials intended to shut down the encampment where she had been living for months, Olga willingly — if reluctantly — climbed aboard a bus bound for what she thought was a temporary apartment that could, one day, become her permanent residence. It wasn’t quite what she expected.

She ended up in a hotel room in Century City, expecting to stay for months. But now, with travel restrictions easing as COVID-19 cases continue to decline, the hotel is reopening, and homeless people, there under the government-funded program Project Roomkey, must leave.

In Olga’s case, that means another hotel room, this one in Monterey Park, miles from anyone she knows.

A homeless encampment at Echo Park Lake has become a symbolically fraught case study of the rights to public spaces

“They’re not truthful,” she said bitterly. “There’s no full disclosure.”

Many L.A. politicians have deemed the clearing of Echo Park a success.

Mayor Eric Garcetti crowed during a news conference that it was “the largest housing transition of an encampment ever in the city’s history.” The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority has said it got some 180 people indoors, the majority going to hotel and motel rooms.

Los Angeles City Councilman Mitch O’Farrell, whose district includes Echo Park Lake, has put the number at more than 200, apparently using his own math. He has praised the end of “a dangerous, chaotic environment.”

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Councilman Joe Buscaino described what happened as moving “people living on our streets into a better situation.” Even Councilman Mike Bonin, who is facing his own grief from residents fed up with a growing line of tents and fires on the streets in Venice, said it was a “major achievement” to get so many homeless people housed.

But if L.A. officials were expecting gratitude from the homeless people they relocated, they might want to temper that.

In recent days, I heard from or spoke to more than a dozen people who got booted from Echo Park. Few were happy.

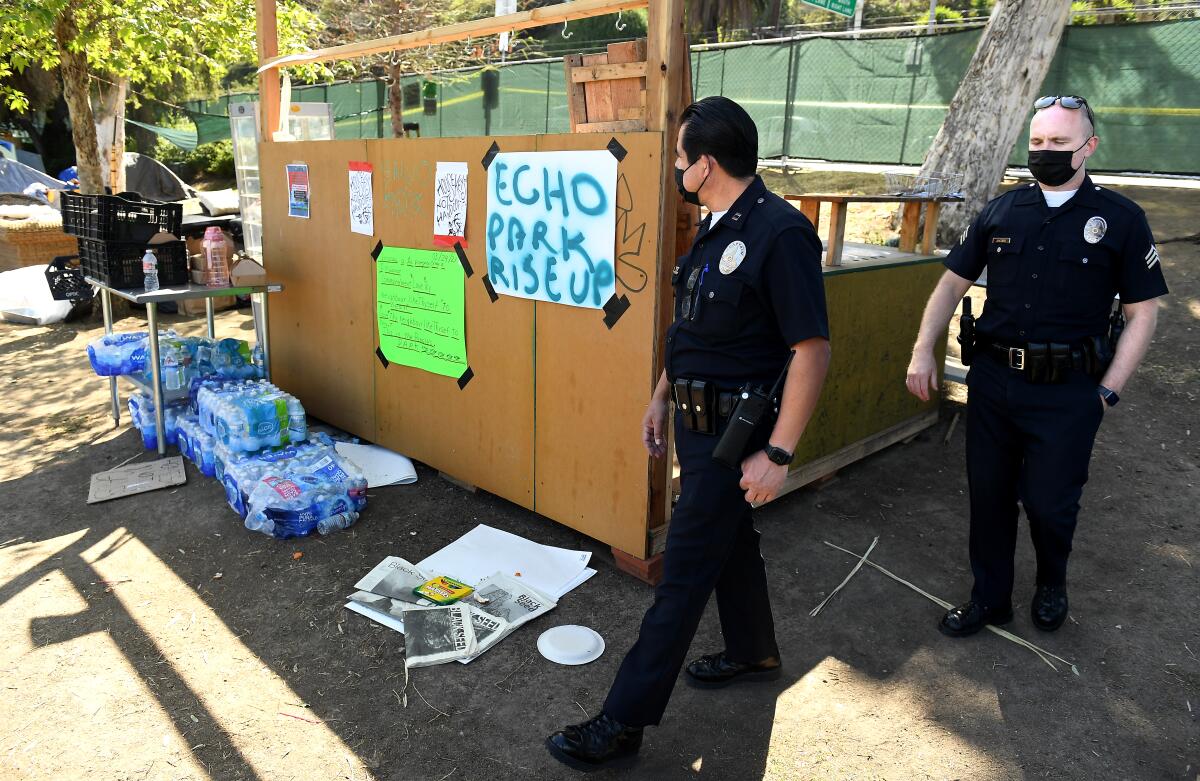

In the week since caseworkers descended on the park, flanked by protesters and a ridiculous number of Los Angeles police officers in riot gear, the airing of such sentiments has become common.

This is gentrification in action. When those with power and wealth cannot achieve their aims through public acquiescence, police violence becomes useful.

At a press conference in front of L.A. City Hall, Ayman Ahmed, who was among the last to leave Echo Park after the city fenced it off, went on a rant.

“I don’t even have my Bible. They tossed it,” he said. “And why? Why did they displace us? For what reason? For this [Project] Roomkey nonsense? These are not adequate alternatives to what we had. What we had at Echo Park was a shelter.”

Those who accepted hotel and motel rooms said they felt jerked around and unfairly put upon by the strict Project Roomkey rules. Some were ready to leave, calling into question whether we can really call the clearing of Echo Park a “success” if homeless people are so unhappy with what happened that they refuse to stay in the housing that’s offered.

Others I spoke to took a pass and remained on the streets. Many continue to camp near a fenced-off Echo Park.

L.A. politicians want to know how much it cost to send in the LAPD as the city fenced off Echo Park Lake and barred people from a homeless encampment there.

All miss the community they built, even as many of the housed residents of Echo Park are applauding the reclaiming of a public space they had lost to tents for more than a year.

C.C., who had been living in Echo Park since November, said she turned down placement at a hotel and instead went to a friend’s house for a few days. Now she’s at what she calls a safe house.

“That’s my home and my family,” she said of her time on the banks of the lake. “We were able to feed each other, thanks to the community, clothe each other, take care of each other, build a community kitchen together. We had a beautiful community.”

Diana, who got placed in a room at the L.A. Grand Hotel Downtown with her boyfriend, Wic, spoke longingly of the community kitchen. “We had so many different donations,” she said. “There were so many different foods, water bottles, crackers, bread, so much fruit. Whatever you wanted to pick.”

“We ate better at Echo Park than we do at the hotel,” Wic added. “And I’m not even gonna lie.”

Although the couple lived at the encampment for months, they were among the first to volunteer to leave. Wic, an aspiring rapper from Miami, took one look at the police officers in riot gear and knew it was time.

“I don’t want to be a dead rapper,” he said.

Brenda, another homeless resident of the park, said she was scared of the police, too. But instead of accepting an offer for a hotel or motel room, she decided to camp out in front of O’Farrell’s office for a few days. Since then, she said, she’s gone back to sleeping on other sidewalks, most of them not far from Echo Park.

“I just couldn’t go sit in a room by myself,” the 60-year-old said, taking a break from doing laundry. “They don’t let you talk to any of the people there with you.”

Brenda had heard about the rules that come with Project Roomkey: the curfews, the temperature checks to screen for COVID-19, the lack of privacy. She feared police officers would show up to enforce those rules if she broke them. It’s a familiar refrain.

Project Roomkey has its upsides, though. Diana said several people in neighboring rooms at the L.A. Grand Hotel also used to live on the banks of Echo Park Lake. She noticed that they have “like, a calmness of maybe having a room.”

But she and many of the others newly housed in hotels also spoke of the very real fear of being kicked out once again. They know Project Roomkey won’t last forever, and living in a room for a few weeks or months doesn’t feel like, as Bonin declared it, a “major achievement.”

“At the end of the day, we have a time limit, when we have to leave,” Wic said. “They haven’t thought of where we’re going to go, because everybody’s not going to get housing. At least that’s what I was told.”

Wic said he’d rather leave with Diana before they get kicked out.

Olga has wrestled with the same thought. But for now, she’s willing to try Monterey Park, even though she doesn’t know anything about the hotel she’ll be staying at. She does know that she wasn’t suited to life in Century City — and that she’s lost something she’s likely never to get back.

“I went to Ralphs, and I felt underdressed. At least in Echo Park, there were hipsters,” Olga said. “I didn’t have the right jewelry. I didn’t have the right clothes. I don’t fit in. I really miss my community.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.