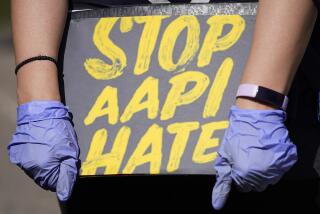

Column: Asian and Black Americans experience racism differently. But we need to unite against hate

- Share via

As an attorney in Southern California, Helen Tran has spent years working behind the scenes to promote economic and racial equity.

But it wasn’t until last summer that she experienced the raw power that mass protests carry, when the death of George Floyd at the hands of police had her marching in the streets — along with hundreds of thousands of people of every race all across the country.

“I had my own awakening then,” Tran said, “about the need for centering Black lives.”

Now she’s hoping that others will be awakened to the need for battling racism, as we mourn the deaths of eight people — six of them women of Asian descent — in mass shootings at three massage businesses last week in Georgia.

A vigil and rally Tran organized in Alhambra last weekend drew primarily Asian American support, but she was heartened by the sight of a lone Black face in the crowd.

“It feels so important to be together against the issue of white supremacy,” she said.

But unity may be a tall order, this time around.

The relationship between Black people and Asian Americans in Los Angeles has been fraught for years — over issues as broad as access to higher education, and as local as the glut of liquor stores in South L.A.

“We don’t have to agree on everything,” insists Tran, whose family came here as refugees from Vietnam. “It doesn’t have to be either/or,” she said. “That’s where we get stuck.”

Racism “is experienced by us differently,” she said. “But the source is the same.… Even when there is intragroup fighting among races, we are still fighting for scraps.”

That’s not surprising, given our respective histories. Both Asian Americans and Black Americans have been targeted by racist laws and acts of hatred for generations, but in recent decades waves of upper-class immigrants have made Asian Americans overall the fastest-growing — and most financially successful — ethnic group in the United States today.

The median income for Asian American families is higher than that of any other group in the United States, and more than twice as much as the Black family median.

In America’s caste system, the descendants of slaves are stranded on the bottom, while Asians are often labeled the “model minority.”

But last week’s shooting rampage, in which an unrepentant white man has been charged, didn’t target executives in glass offices or tech gurus courting high salaries. The victims were working-class women, some single mothers, toiling in low-status jobs, laboring to salvage an imperiled business, trying to provide for their families.

As a Black woman, I can’t help but feel that these deaths have drawn Asian Americans into our fold. The stories of the victims’ lives spotlight the common ground our groups share as targets of mass violence fueled by racism and inhumanity.

The shootings, law enforcers quickly assured us, did not appear to be racially motivated. The man charged with gunning down eight people was just having a “really bad day,” said Capt. Jay Baker, the sheriff’s spokesman.

That spokesman was later linked to a Facebook post urging people to buy a T-shirt bearing the words “Covid 19 IMPORTED VIRUS FROM CHY-NA.”

And we wonder where the hate comes from.

The rampage — and the rationalizing — reflect the dehumanizing impact of the bigotry and stereotyping that America’s disfavored groups are subjected to.

I grieve now for these Atlanta women — just as I grieved the nine Black worshipers murdered at a Charleston, S.C., church. And the 23 people killed by a gunman targeting Latinos at an El Paso shopping center. And the 49 people massacred at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Fla. And the 11 Jewish worshipers shot to death during a Shabbat service at their Pittsburgh synagogue.

There’s an undercurrent of fear in the Asian American community now; a feeling familiar to families like mine, who have learned to fear both the streets and the police.

We know that no matter how good your grades or how high your income, you may still be seen and sorted primarily by your skin color, your accent, the texture of your hair — by people who refuse to see your humanity.

But like Helen Tran, I also see the potential for this tragedy to expand the social justice movement that has Black lives as its nexus, and the eradication of racism as its goal.

“There’s a lot of racism in the Asian American community against Blacks and Latinos still,” Tran acknowledged. “But there has also been a lot of Black and Asian solidarity.”

I see that same dichotomy from my side of the fence. I cringed last week, when I came across a video of a young Black man in Oakland shoving an elderly Asian man to the ground. But the next day, I encountered Black volunteers in Oakland’s Chinatown, guarding the streets so older Asian women could shop safely.

We are beginning the process of trusting each other. That’s the first step in working together for justice.

And Tran has seen that too, in her own family. She got help organizing the rally from her cousin Raymond, who works as an engineer and had never been to a protest before.

He didn’t join the marches last summer because he was busy helping his parents keep their nail shop afloat. And it was easy to think that George Floyd’s death had nothing to do with him.

“But he’s very aware now that when our community is struggling, Black people are showing up,” Tran said. “Now it feels very personal to him — the responsibility to protect his family and community.”

That is how I felt last summer, and the diversity of the protesting throngs was supremely gratifying.

Now the question is: Can we join together and move forward, with white supremacy — not each other — as the enemy?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.