As a 9-year-old, she was saved at sea. Thirty-five years later, she reunited with her rescuers

- Share via

She had been drifting in the cold Pacific water for a night and most of a day.

Kept afloat by her orange life jacket and the bow of her family’s capsized boat, 9-year-old Desireé Rodriguez had watched helplessly as one family member after another let go of life.

First her mother began foaming at the mouth and then went still. Her 5-year-old sister died soon after. Her uncle went next, followed by her aunt.

Now she was alone, with no idea where her father was. He’d been at the helm during what started as a routine fishing excursion on the family’s boat. Soon after it flipped over, miles from land, he had insisted on trying to swim for help through the dark and thick fog.

Just as Desireé, too, began to give up, the skipper of a commercial sportfishing boat spotted an orange smudge bobbing in the water through his binoculars. Within minutes, the boat’s first officer had leapt into the water and was grabbing Desireé’s life jacket, pulling her back toward the boat — and toward life.

A 9-year-old girl was rescued from the sea Monday after she spent more than a dozen terror-filled hours clinging to the wreckage of a pleasure boat that capsized 11 miles south of the Palos Verdes Peninsula.

The crew radioed the Coast Guard, then transported the girl back to San Pedro, where medics wheeled her off the boat in a stretcher. That was the last time the rescuers and the girl saw one another. Until this year.

A fishing expedition

May 18, 1986, was the kind of beautiful, sunny day that regularly brought the Rodriguez family to Catalina Island for some fishing on their 28-foot pleasure boat, DC Too.

Desireé’s father, a 30-year-old construction worker named Thomas Rodriguez, loved the sport, especially catching bass. A strong, slender man, he had instilled in his oldest daughter a love of the outdoors, teaching her how to bait a hook and cast a line. Sometimes he took her three-wheeling in the mountains near their Riverside home.

As was their custom at least once a month, the family boarded their boat that May morning for a carefree day trip. For the first time, Thomas’ sister, Corinne Wheeler, 33, and her husband, Allen Wheeler, 34, had decided to join them, leaving their three children at home in the Riverside neighborhood where both families, as well as Desireé’s grandparents, lived. After a day of fishing, the family left the island in the early evening, a bit later than usual, and soon dense fog had rolled in.

Desireé fell into a light sleep beside her 5-year-old sister, Trisha, at a table on the boat’s lower deck. Their father’s sharp orders startled her awake: “Get out of the boat. The boat’s sinking!”

Desireé pushed her sister into the cold, dark water, both of them in life jackets. They were followed by their mother, Petra, a petite, quiet 29-year-old who was pregnant.

Within seconds, the boat capsized fully, leaving just the tip of its bow in the air — and the six family members stranded in the chilly Pacific water. Looking into the faces of her father, mother, aunt, uncle and sister, Desireé wasn’t frightened.

“It was like what you would see in a movie,” she recalled in a recent interview. “You could see nothing around you. It was just dark. But it was peaceful, quiet.”

After some time, her father told them he would swim for help. “I’ll be back,” he said, before disappearing into the darkness.

“My dad was like the superhero to me. I actually thought he would get help,” Desireé said.

When her mother died, Desireé wrapped a rope around her chest and tied her to the boat, so she wouldn’t float away. At some point, her sister died too.

“I remember it was just pretty much quiet after that,” Desireé said. “I think we were all just kind of in disbelief, and just waiting.”

‘At that point, I just kind of made the decision, I need to get away from this boat. I need to swim away, somewhere else. ... Where? I don’t know.’

— Desireé Rodriguez

Aboard the First String

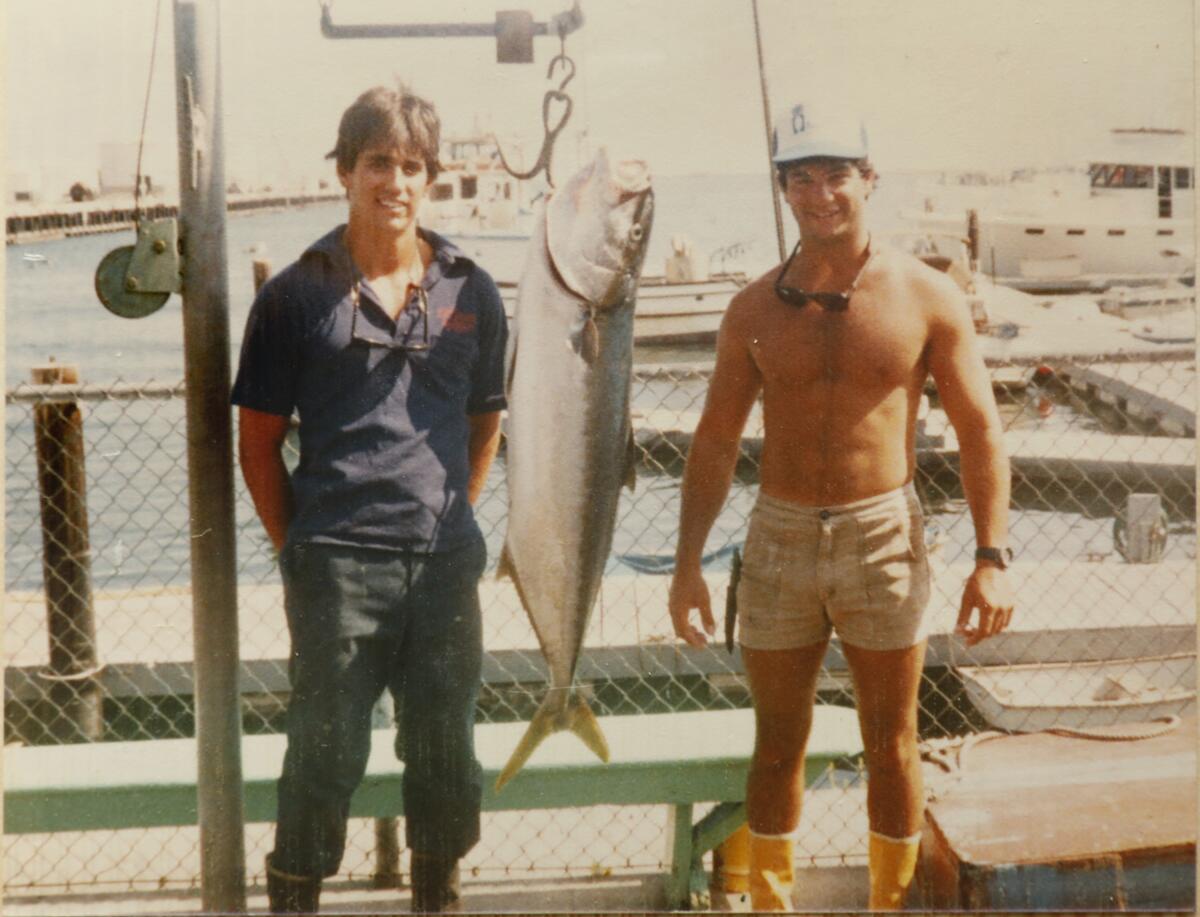

Paul Strasser and Mark Pisano, two strapping 23-year-olds, were still new to captaining ships when they pushed off from San Pedro with 35 passengers aboard the First String, a boat they’d helped build, at 6 on the morning of May 19.

The best friends had met as 14-year-olds, when Pisano collected Strasser’s passenger ticket on a morning trip to Horseshoe Kelp in the L.A. Harbor. Soon after, Strasser quit his job delivering newspapers to join Pisano on the fishing boats, where they scrubbed decks, cleaned fish and earned the title of “pinheads” — eager young fishermen learning the ropes of the trade.

The two graduated from pinheads to deckhands and eventually to full-fledged fishermen, able to work not only on commercial fishing expeditions but also whale-watching cruises and at bait-and-tackle businesses. They hung out together during school breaks and attended frat parties, but mostly they spent their free time learning their trade. Before long, they became two of the youngest captains at San Pedro’s 22nd Street Landing.

Their fishing trip on May 19 began uneventfully. Pisano remembered the weather was “pea soup fog” — so thick you couldn’t see the stern of the boat — and the fish weren’t biting all morning.

“We were going to try one more spot and then go home,” Pisano said. But then, some yellowtail, a prized game fish, “started biting out of the blue.” The fishermen hung around for another couple of hours, pulling in fish after fish.

By then, the fog had cleared, and the sun was shining.

Meanwhile, Desireé and her two remaining family members were slipping in and out of consciousness. To keep themselves awake, Desireé and her aunt daydreamed about how they would be rescued. They would stay in a hotel, order room service and burrow under the blankets in bed, cozy and warm.

“We kind of still had hope,” Desireé said. “Like, we’re going to be OK. We’re going to come out of this.”

Her uncle evidently didn’t share their hope. With the afternoon sun now high overhead, she recalled, he swam away from the boat.

“He just kind of gave up,” she recalled.

Desireé swam after him, propelled by her aunt’s plea: “Don’t let him drown.”

She caught up with him quickly but then struggled to keep her tall, stocky uncle above water. She finally had to let go, and he slipped beneath the surface.

Desireé doesn’t remember how or when her aunt died. But soon, the 9-year-old became aware that she was alone in the ocean.

“At that point, I just kind of made the decision, I need to get away from this boat,” Desireé remembered. “I need to swim away, somewhere else. ... Where? I don’t know.”

Hashem Ahmad Alshilleh’s children didn’t fully realize the impact he’d had performing Muslim burial rites for decades until he died, and tributes began to pour in.

The rescue

Late that afternoon, Strasser and Pisano set off on the return voyage to San Pedro, with their haul of fresh-caught yellowtail. One of the crew members went to the lower-level bar for a cocktail. Strasser sat behind the wheel, which was set to autopilot.

Then, about seven miles away from the island, he noticed something white flashing in the water about half a mile away. He steered the First String toward it and peered through his binoculars, thinking it might have been a boat bumper.

“The closer I got, the more like a bumper it didn’t look,” Strasser recalled. “We’ve got something going on here, this is weird.”

He told Pisano, who’d joined him in the wheelhouse, to get ready to jump into the water.

“When I pulled up to it, I saw a dead body facedown,” Strasser said, referring to Desireé’s mother. “It was tangled up in all this rope. ... I said, ‘Oh boy, no one’s been here before.’”

Strasser radioed the Coast Guard but was interrupted by passengers yelling below. In the commotion, he noticed two other people in the water: One was Desireé’s aunt, floating facedown. The other, wearing an orange life jacket, was bobbing with the swells, her head and brown hair visible just above the water.

“I knew if it had a life jacket, and I saw a brown thing above it, we have a chance,” Strasser said. He steered the boat toward Desireé, who recalls seeing figures on the big white boat.

“To me, it was like the Titanic,” she said.

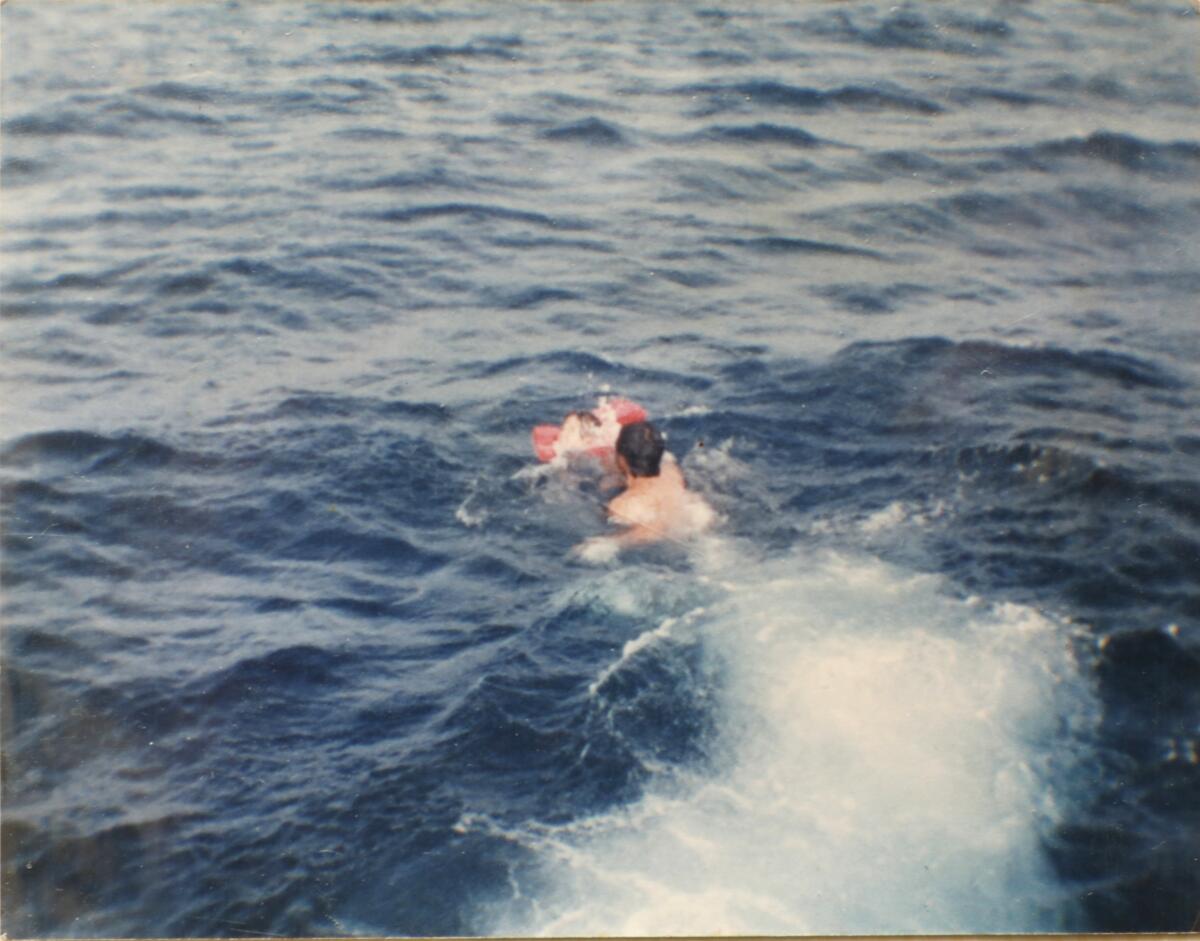

As soon as he saw that she was alive, Pisano stripped down to his underwear and jumped into the cold water. Pumping with adrenaline, he swam toward her and grabbed her life jacket. From her near-unconscious state, Desireé flinched. Pisano swam her back to the boat, where Coast Guard medics immediately covered her in warm water bottles that felt prickly on her cold skin.

Desireé, now 44, remembers being flooded with relief.

If the boat hadn’t come right then, she says, “I don’t think I would have lived, I’ll be honest with you. I think at that point, I was just kind of done.”

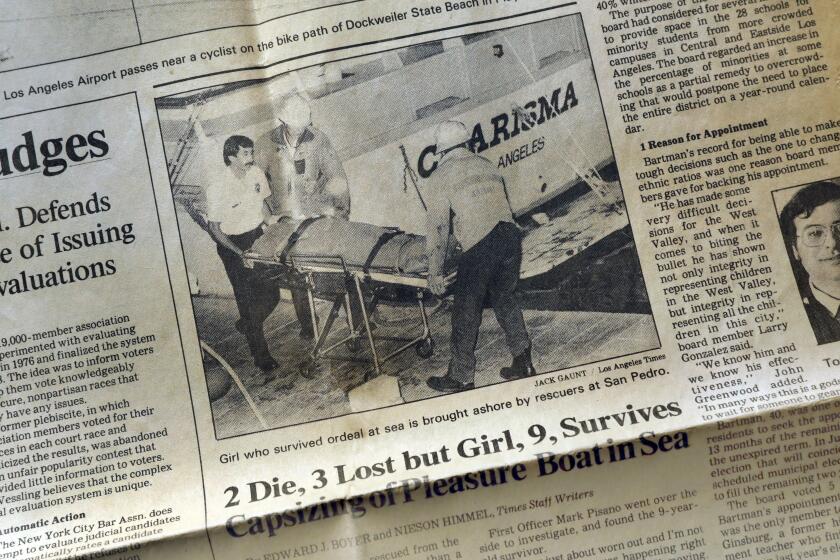

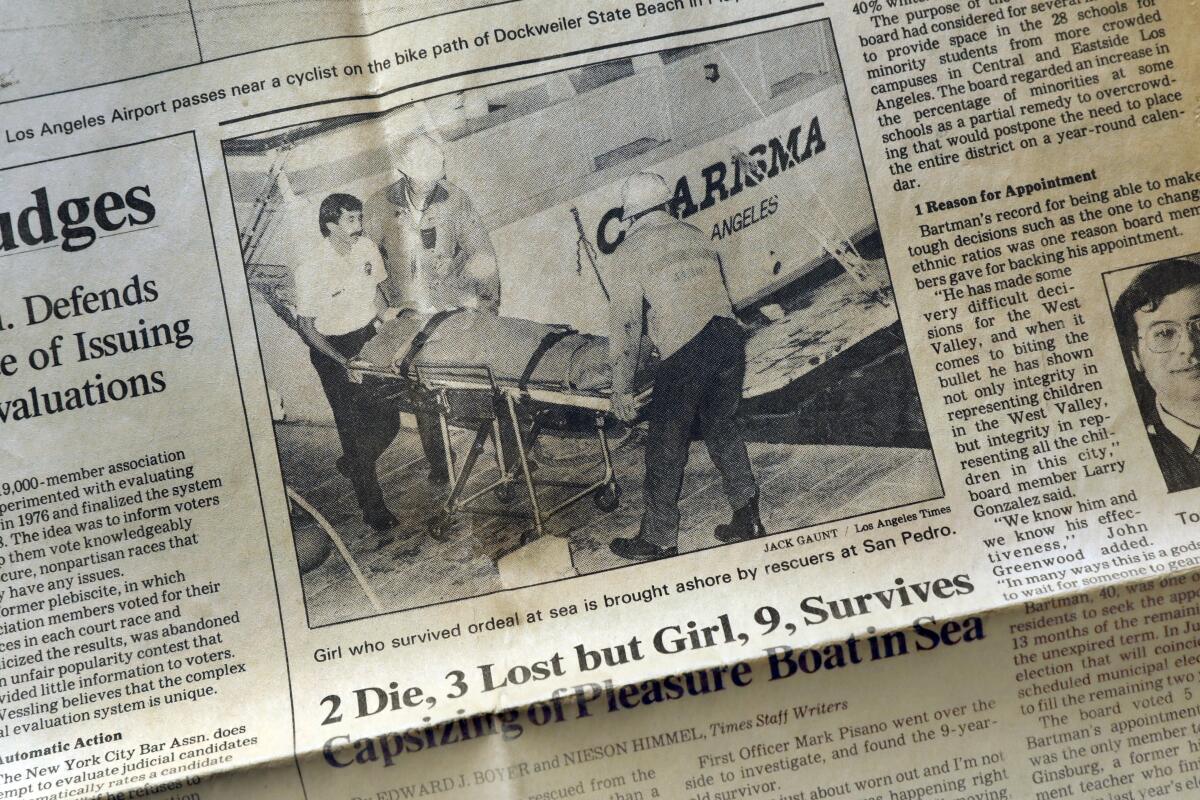

When the fishing boat pulled into the 22nd Street Landing, a swarm of news cameras and buzzing helicopters greeted them. “2 Die, 3 Lost but Girl, 9, Survives Capsizing of Pleasure Boat in Sea,” read the Los Angeles Times headline the following morning.

A Coast Guard spokeswoman said in the article that Desireé had “a strong, resilient constitution” and apparently suffered no major physical injury. She was “in good spirits” despite her long wait in the ocean. The little girl walked out of San Pedro Peninsula Hospital the next day after being treated for exhaustion and hypothermia, according to The Times’ archive.

Officials didn’t find any sign of collision when they pulled the family’s boat, the DC Too, out of the water, concluding that a large swell, perhaps from the wake of a passing ship, may have capsized the boat. The search for Desireé’s father, sister and uncle was abandoned two days after her rescue.

“I had even hoped that my dad did make it somewhere,” Desireé says now. “Maybe he is living on an island and just got amnesia and didn’t know that he has a family. You know, you always have hope. But you get older, and reality sets in, and you’re like, OK. He didn’t make it.”

Strasser and Pisano earned commemorative plaques for their bravery from Mayor Tom Bradley.

Desireé Rodriguez, now Desireé Campuzano, was adopted and raised by another aunt and uncle. No one asked about her experience in the water. They didn’t want to traumatize her again, Desireé said. She attended therapy sessions for a while as a child but found them unhelpful. Mostly, she coped by herself and tried to be a good person, guided constantly by the question, “What would my parents expect of me?”

Desireé attended junior college in Fullerton and Cerritos while building a career in criminal justice. She married in 2013 and, five years ago, had a son.

In her late 20s, Desireé began to wonder about her rescuers. She sent Oprah Winfrey a message, trying to get help. Strasser and Pisano sometimes thought of her, too, especially whenever anyone asked, what’s your craziest story at sea? But neither Desireé nor the men who saved her knew where to start looking.

“Desireé was a ghost,” Strasser said. “We saved her, she’s out in the world. And that’s all we know. We had no clues on anybody that knew how to get ahold of her.”

The reunion

When the COVID-19 pandemic derailed Philip Friedman’s plans to return to his teaching job near Shanghai last year, the 62-year-old fishing aficionado decided to stick around Southern California with his family and make a podcast about his hobby.

“Friedman Adventures” launched in December, broadcasting stories from fishermen around the wharf talking about boats, catches and fishing tips. One episode featured Pisano talking about the 1986 rescue.

“It’s kind of a weird story, kind of like there are some supernatural qualities,” Pisano said on the podcast.

Never experiencing the relief of seeing COVID patients recover takes it toll on crematorium workers. One worries he’ll develop a ‘hard heart, a cold heart.’

Friedman said he felt a tingle crawl up his spine on hearing the tale.

“My brain was like, I’m going to try to locate her,” Friedman said. “We’ve got to finish this story!”

The same day that the episode was posted online, 41-year-old Pablo Peña tuned into the show on his 20-minute commute to work as a railroad engineer in Commerce. Peña had been following Friedman’s first season diligently, having met the podcaster a decade earlier on a fishing excursion. Pisano’s story triggered a memory.

‘Desireé was a ghost. We saved her, she’s out in the world. And that’s all we know. We had no clues on anybody that knew how to get ahold of her.’

— Paul Strasser

Peña remembered a conversation he’d had at least 17 years earlier with a former co-worker. She’d made an offhand comment about losing her parents in a boating accident and being the only survivor. He hadn’t asked any questions then, not wanting to broach a sensitive subject.

“It started to churn my wheels, and I was like, well, it could be her,” Peña said. “But he would have to say her name was Desireé Rodriguez to make this solid.”

“Her name was Desireé Rodriguez, the girl we rescued,” Pisano said on the podcast. “There’s like, I can’t tell you, how many Desiree Rodriguezes in L.A.”

Peña replayed the segment. “I was like, holy moly,” he said. “Wow, this is just surreal.”

Peña immediately sent a message to Friedman.

“I was like, ‘You gotta be friggin’ kidding me, dude,’” Friedman said. “Give me a break.”

First, Friedman reached out to Desireé, to ensure she wanted to meet her rescuers.

“I was just like, this is weird. Not a bad weird, but it’s just kind of eerie,” Desireé said. Watching the podcast video, she grew emotional. “After all these years, for this to come up — what are the chances? Very slim.”

Friedman concocted a plan to surprise the two fishing captains with the woman they’d rescued 35 years ago — all recorded for his podcast.

“I thought it would make for a dramatic, interesting way to do it,” Friedman said. “Something that those two guys, I think, will never, ever forget.”

Desireé showed up at the 22nd Street Landing a few days later. The podcast video shows her walking into the studio, under the guise of Raquel, supposedly a translator who was going to retell the captains’ rescue tale on Spanish television.

“I was nervous at first,” Desireé said, “just seeing [the] guys and putting kind of finalization to the ‘what happened.’”

All smiles, she listened to her rescuers recount their side of the story, clueless to her true identity.

“Wow, that’s so great that you guys were able to do that,” Desireé said on the video. “And you guys haven’t even had any contact [with Desireé]?”

After almost 10 minutes, Friedman broke the gag.

“Boys, I want to tell you something,” he said. “This is not a translator. I’m going to let her introduce herself to you.”

Almost a year has passed since Gordan and Diane Norman last saw each other in person — separated by Alzheimer’s and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Pisano slapped the table in an instance of recognition. Everybody crumpled into tears.

“I’m Desireé,” she said, her voice wavering.

Amid hugs, tears and exclamations, the story that united three strangers across decades came tumbling out.

“I feel like she’s sort of our daughter, in a way, because we brought her back to life,” Strasser said. “Even though we never knew each other.”

In the couple of weeks since they reunited, Strasser said he’d spoken again to Desireé on the phone. Pisano introduced her to his wife and daughter. After watching the video dozens of times, Friedman still cries. Peña has shared the clip with friends and family, reveling in their reaction.

For years, Desireé wondered about the men who rescued her. Now that she’s met them, she says she hopes to stay connected forever.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.