‘Real Housewives’ attorney Tom Girardi used cash and clout to forge powerful political connections

- Share via

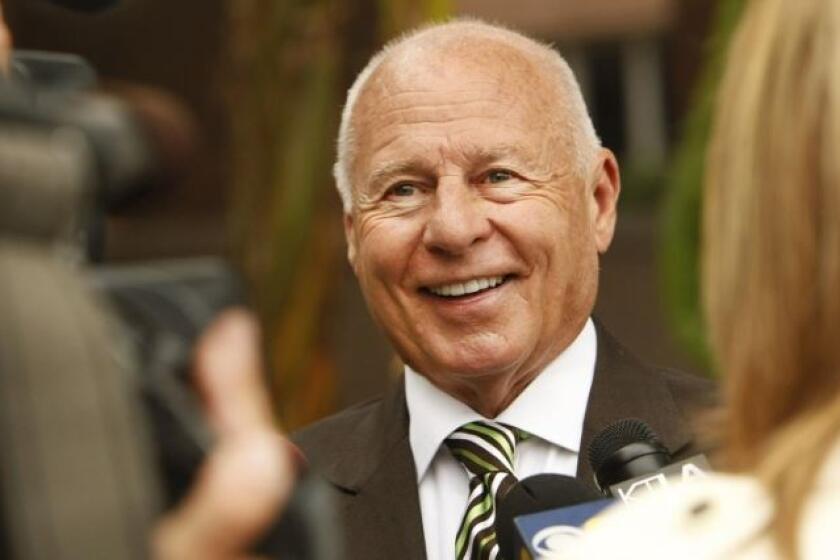

When Joe Biden came to Los Angeles to raise money for his presidential campaign, Tom Girardi filled a dining room at the Jonathan Club with wealthy attorneys.

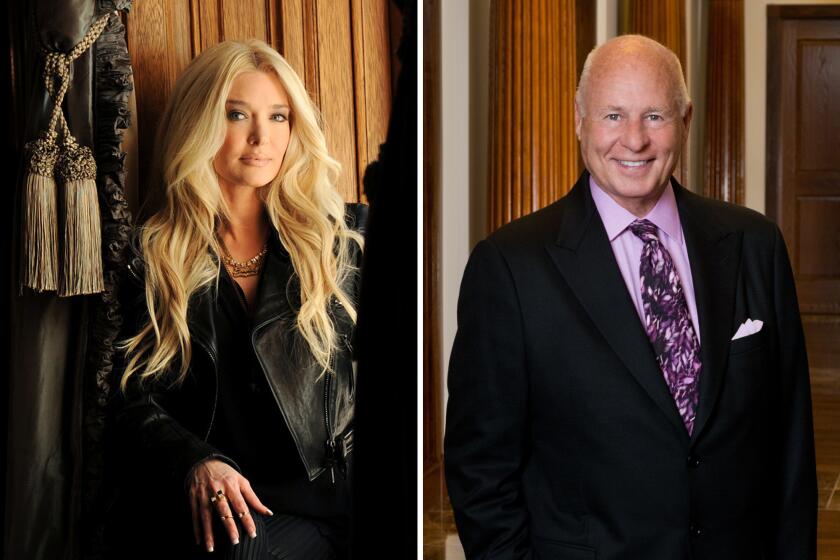

“Obviously everyone thinks the world of you — and they should,” Girardi told Biden as his then-wife, “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” star Erika Jayne, looked on in a stylish blue dress.

The 2019 breakfast fundraiser at the private downtown club was in many ways the end of an era. By the time Biden was elected last fall, Girardi’s life and legal empire were unraveling. His wealth, once estimated north of $250 million, has vanished and with it his reputation as one of the nation’s most connected and respected lawyers. With Girardi facing bankruptcy, divorce and a criminal investigation, his days as a political insider and power broker appear over.

For decades, though, politicians were happy to take his money and put up with his requests for something in return. Along with his family and employees, Girardi contributed more than $7.3 million to candidates.

He could get Govs. Gavin Newsom and Jerry Brown on the phone with ease, associates said. He and Jayne regularly traveled to Washington, D.C., where then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid appointed him to a Library of Congress board. Former Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy spoke at the 2002 dedication of a Loyola Law School building named for Girardi’s father.

The couple went to political events or dinners constantly, Jayne recalled in her autobiography, “Pretty Mess,” sharing a table with Barbra Streisand at a Clinton fundraiser or discussing L.A.’s homeless problem at an intimate dinner with the mayor and his wife.

Tom Girardi and his firm were sued more than a hundred times between the 1980s and last year, with at least half of those cases asserting misconduct in his law practice. Yet, Girardi’s record with the State Bar of California remained pristine.

“We would have drinks with a U.S. senator, and she’d confide in us the problem the senators were having with the current administration,” Jayne wrote in the 2018 book. “These were some great experiences.”

From the winning candidates he supported, Girardi sometimes expected favors, whether it was an appearance on his weekly radio show, a say in judicial appointments or a backroom deal that would help his law practice, according to interviews with longtime associates, state bar litigation records and an unpublished memoir.

Former state Atty. Gen. Bill Lockyer, for whom Girardi raised hundreds of thousands of dollars, said in an interview that their friendship fell apart over requests for favors that he felt were unethical.

Back in 2005, Girardi wanted Lockyer’s permission to let him resolve government antitrust claims against Sempra Energy as part of a separate, private settlement agreement he was negotiating, Lockyer said.

“My impression was [he thought] Sempra might be more generous on their settlement side if mine went away,” he recalled. Lockyer refused.

In the same period, he said, Girardi lobbied him not to pursue charges against Hewlett-Packard chair Patricia Dunn, who was under investigation for allegedly directing a boardroom spying program, and instead to go after a young, low-level participant, Lockyer said.

“I remember at the time saying to Tom, ‘I can’t do that. Will you think about justice?’,” Lockyer said. Girardi ended their friendship with a letter that stated, “I never want to talk to you again.”

At the time, Lockyer recalled, “I considered him one of my best friends.”

Girardi’s most consistent request of politicians was a say in which lawyers got seats on the bench.

“I make no bones about influencing judicial appointments. Awful, you say? Unethical? Well, who better to recommend a man to the bench than someone who works with him every day,” he wrote in the memoir entitled “May It Please The Court.” His ghostwriter, Dennis McDougal, shared a copy with The Times.

While some judges are elected in California, governors fill vacancies and nominate appellate and Supreme Court posts. Girardi’s connections with governors dated to the early 1970s, when he worked to get Brown elected. It’s not unusual for an attorney to offer an opinion on a prospective judge’s fitness, but Girardi’s role went well beyond that. He often told stories of how he and other legal insiders met in the back of a private club to decide which of their L.A. peers were deserving of judgeships.

Girardi described in the memoir how he would then surprise the aspiring judge by having Brown swear the new jurist in during a dinner party at his Pasadena home. The former governor did not respond to questions about Girardi’s account or their relationship.

Tom Girardi is facing the collapse of everything he holds dear: his law firm, marriage to Erika Girardi, and reputation as a champion for the downtrodden.

Attorneys throughout California began to turn to him for assistance in getting on the bench. In one example, Girardi pressed the chief of staff for then-Sen. Barbara Boxer to throw her support behind L.A. Superior Court Judge Carolyn Kuhl’s unsuccessful nomination to the federal appellate bench in 2003, according to an account at the time in the Daily Journal.

“She’s conservative. But she’s honest,” the paper quoted Girardi as telling Boxer’s top aide, who responded that the senator highly valued his opinion.

Girardi pushed for other state court judges who did make it onto the federal bench, according to congressional records. When then-Superior Court Judge S. James Otero was up for a U.S. District Court seat in 2003, Sen. Dianne Feinstein told the judiciary committee that she was prepared to provide “many quotes” about the candidate from Girardi among other supporters.

Later Girardi appeared to be coordinating efforts to promote judicial candidates with his close friend, state bar investigator Tom Layton. Emails uncovered during a lawsuit Layton brought against the bar suggest the former sheriff’s deputy was acting as Girardi’s gatekeeper with prospective judges.

In one 2014 message, a deputy attorney general, Kim Nguyen, informed Layton she was working on her application and would “send you and Mr. Girardi an updated version shortly.”

“We are already on board,” Layton replied. Nguyen was elected to L.A. Superior Court in 2016. She did not respond to a message seeking comment.

Several top bar officials, including board presidents, also received offers of help from another Girardi pal, bar executive director Joe Dunn, to get court positions, according to an internal bar report that found such offers were harmful to “proper governance.” The report also recounted how Layton approached Jayne Kim, a prosecutor at the agency, and held out “assistance from Tom Girardi in helping her to become a judge or to achieve some other professional goal.”

Questioned under oath, Layton denied making the offer to Kim and downplayed his role in judgeships.

“Are there things Mr. Girardi can do to help people become a judge?” asked the bar attorney conducting the deposition. After Layton said he didn’t know, the attorney replied, “Well, I think you do know.”

Newsom broke with his predecessors in 2019 and publicly revealed the advisors who help the governor select judges. Girardi was listed on the panel that evaluates potential jurists in L.A.

What Girardi got in return for his efforts is not easily quantified. He maintained warm friendships with judges, especially in Southern California. He was often seen dining with them and many attended the bashes he threw each year in Las Vegas when plaintiffs lawyers gathered for a convention. He sometimes presented himself as speaking for members of the judiciary, such as in a letter to former L.A. County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey.

“Several judges and justices have mentioned to me that it would be great if you support AB 2205,” Girardi wrote in 2016, referencing a public safety reform being debated in Sacramento. Lacey wrote back, assuring him her office was supporting the measure.

The cozy relationships sometimes attracted criticism. In 1997, he and another lawyer spent $350,000 to charter a Mediterranean cruise ship whose guest list included 10 active or retired judges. When The Times discovered the junket and contacted the judges, most of the jurists said they had reimbursed the cost of the trip or planned to.

For some who faced Girardi in court, like Carlsbad attorney Terence Mix, the esteem Girardi held among judges was striking.

“We were in chambers discussing the case and Girardi comes in, and the judge, who was sitting behind the desk, stood up and said, ‘Oh, Mr. Girardi, I’ve never met you before,’” Mix recalled of a 2013 legal malpractice case. “I was like, ‘What are you going to do? Genuflect?’ It was clear he revered him.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.