How a picture in a newspaper unlocked childhood mysteries for two Holocaust survivors

- Share via

Last spring, when the pandemic forced a global lockdown, Holocaust survivor Marion Ein Lewin wrote a moving piece for this newspaper, extolling the power of the human spirit and calling on everyone to summon their strength and resilience.

“Celebrating Passover during the COVID-19 pandemic brings back memories of Seders spent in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, starting when my twin brother and I were 6 years old,” began Lewin’s op-ed. “At 82, we are in all likelihood the last surviving twins of the Holocaust — in any case, a shrinking remnant of the 5% of Jews from Holland who were deported to Nazi camps and returned.”

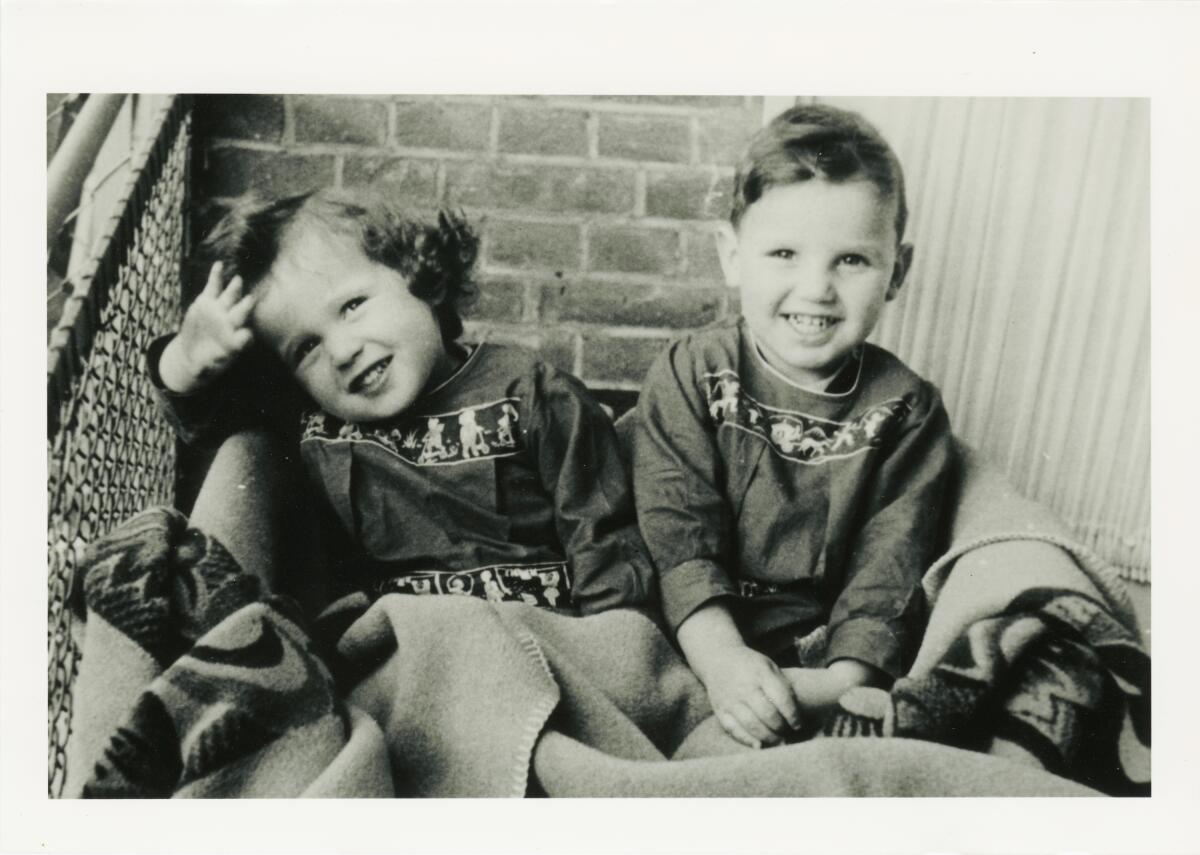

The commentary was accompanied by a black-and-white photograph, supplied by Lewin of her and her brother, Steven Hess, shortly before their entire family was arrested in 1943 and transported by train from their home in Amsterdam to a series of concentration camps. The youngsters were indisputably adorable in their Dutch costumes, a portrait of youthful innocence in a time of unconscionable evil.

When Lewin offered the photo for use with her article, she and her brother — now 83 — could not have dreamed it would make its way back to the Netherlands. But it did, and 75 years after the liberation of Bergen-Belsen and the end of World War II, they were about to have some of the mysteries of their childhood unlocked.

***

Trudie Kramer Feay was in the kitchen of her home in Sunland last spring when her husband, Doug, called out to her from the family room.

“You won’t believe this,” he said.

Feay, a retired L.A. Unified teacher’s aide, went to see what was up and found her husband pointing to Marion Lewin’s op-ed in the L.A. Times.

“Look at this, Trudie,” said Doug, a retired geologist. “These kids are in Urker costumes.”

Doug is U.S.-born but has a Dutch branch in his family tree and has traveled many times to Holland with his wife. She spent her early childhood in the Netherlands, and her grandparents were born and raised in Urk, a small fishing village known for a specific type of ornate costume.

With one glance at the newspaper, Feay knew her husband was right about the outfits. In fact, she’d dressed her own children and grandchildren in similar costumes here in the U.S.

“The cut is different than any other costume in Holland,” Feay explained.

After reading Lewin’s article, Feay wanted to know more about the early lives of the Jewish twins and how they came to be wearing those costumes. During the war, her own family had been involved in the resistance.

“My uncle hid the Jews,” Feay said, describing her relative Hermanus Jansen as a staunch Christian and member of the underground in the Urk region.

At great personal risk, her uncle and other resistance members would also race to the site of downed Allied aircraft to rescue survivors and hide them from the Nazis, and some resistance members also fed, hid and transported Jews to safety. In fact, Feay said, her uncle’s service earned a commendation from then-Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, an honor that made it easier for the family to relocate to the United States in 1956.

Feay texted a link to the op-ed to her longtime friend Jellie Oost, who lives in Urk, asking whether Oost could turn up any information about the Jewish twins and their nanny.

Oost knew just who might be able to help.

***

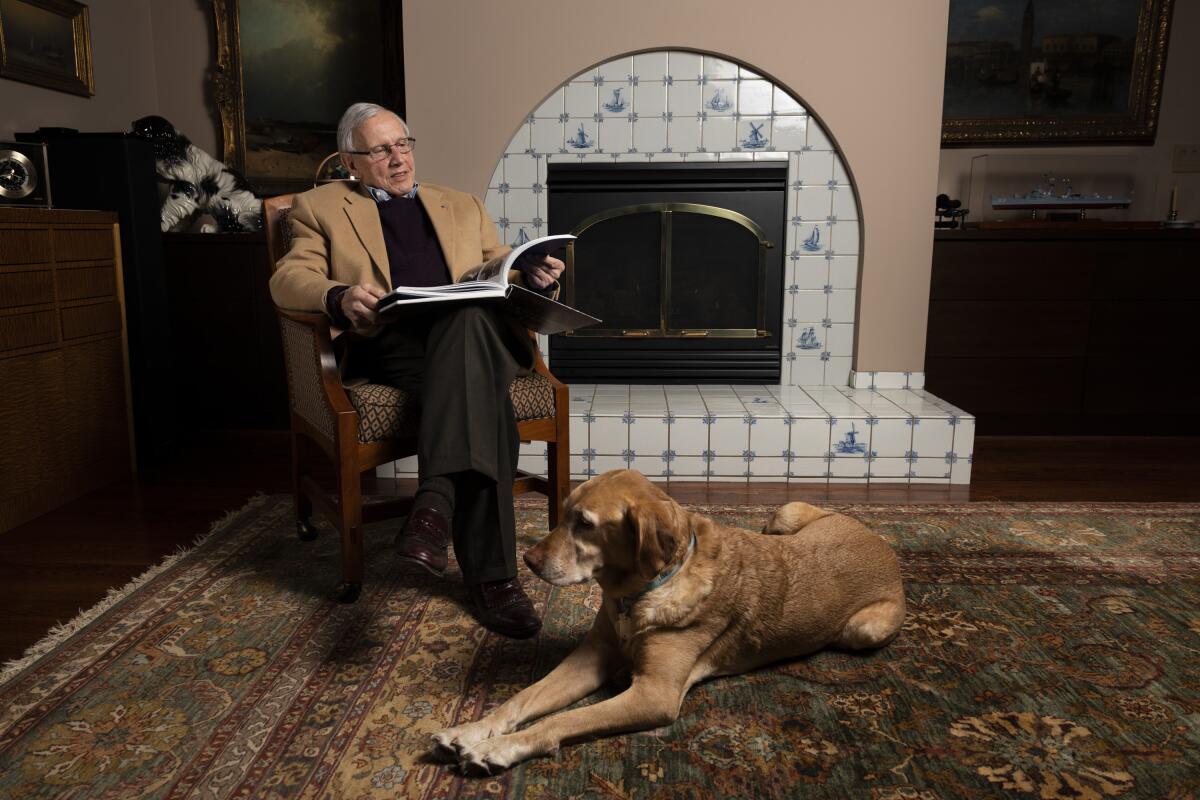

Lub van den Berg is a police sergeant in the town of Zwolle and lives in Urk, where he plays trombone in a brass band, volunteers at the museum of local history and writes for a magazine that covers regional affairs. His family has lived in the area since the 16th century, and he loves exploring the past, especially the period of the second World War.

When Oost sent the Los Angeles Times commentary to Friends of Urk, a historical society, her request for some investigative assistance landed in the hands of the right guy. Van den Berg had served as a detective before his bum knees put him behind a desk at the police station.

“I immediately knew these children were dressed by a lady from Urk,” said the sergeant. He also knew that prior to the war, women from that region traveled to Amsterdam, an hour or so to the southwest, where they worked as domestics for Jewish families.

Van den Berg knew a history teacher who was researching the female labor force during the war. That teacher, Arjan Baarssen, had located a registry of domestics and their employers in municipal archives. The cop sent Baarssen The Times op-ed, and a quick match was made.

“In two days, he gave me the name and address of the nanny,” Van den Berg said.

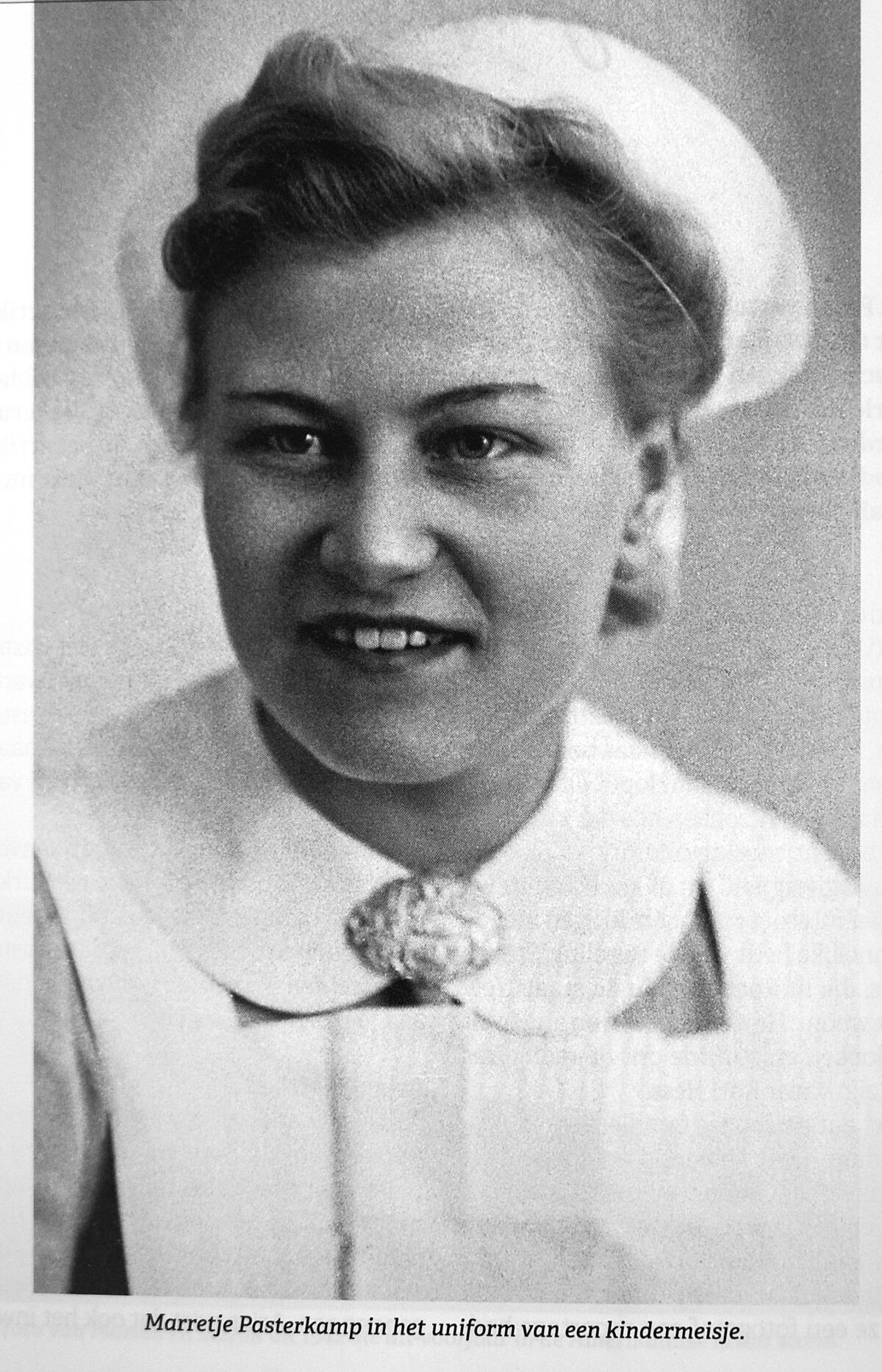

The nanny, Marretje Pasterkamp, had died in 1999, but Van den berg was able to locate two of the nanny’s daughters, who shared what they knew about their mother’s work as a nanny and her life after that.

“She loved the twins so much,” said Ellen Hoogenstrijd De Zwart, the eldest of the nanny’s four children. De Zwart said her mother told her stories about training at an academy to become a governess and traveling to Amsterdam because there was no work in Urk. She said her mother made winter coats for the twins, fearing they’d be nabbed by the Germans during a winter freeze.

“She had so much courage,” said De Zwart in an interview for this story, adding that during the war, some members of her mother’s family were in the resistance.

De Zwart said her mother took a fall on ice in 1944 and suffered a serious back injury that left her disabled for the rest of her life.

And there was one more detail of note.

De Zwart said her mother named some of her own children after the kids she took care of as a nanny.

“I have a sister named Marion,” she said.

Marion Lewin had no idea.

“That is astonishing and so emotional to discover,” she said.

Early in his research, Van den Berg tracked down the Hess twins in the U.S. and began an email dialogue with Steven, who serves as the family’s historian.

Hess sent Van den Berg a copy of his father’s unpublished memoir, and with information from various sources in front of him, the police officer wrote a compelling narrative of intersecting lives, resilience and rebirth. The story ran last July in Urker Volksleven magazine under Van den Berg’s byline. The headline was straightforward: Jewish Twins in Urker Costumes.

***

Pasterkamp, the nanny, was born in the Urk area in 1915. Van den Berg got hold of a photo of her as a young woman in her white nanny’s uniform, with a crescent chapeau clipped to her blond hair and a gold broach at her collar.

She went to work for Karl and Ilse Hess in 1941. The family had fled Germany in 1936, mistakenly thinking they’d be safe from Nazi persecution in Holland. After Pasterkamp was hired, she lived with the Hess family and did her best to care for and entertain the twins despite rising tension in Holland as the war escalated.

“But in 1942 the terror began in full for the Jewish community,” Van den Berg wrote in his story. “The family eventually had to say goodbye to nanny Marretje when Jews were forbidden from hiring non-Jewish help.” But before leaving, the nanny dressed the twins in the Urker costumes, which came from her brother Klaas.

The German police arrived at the Hess family apartment at 2 a.m. July 23, 1943, arresting the entire family and sending them to a camp in Westerbork, in northeastern Holland.

Early in 1944, the Hesses were sent to Bergen-Belsen in northern Germany. While the prison had no gas chambers, it was a factory of cruelty and suffering. Starvation, forced labor, torture, bitter cold, disease and death were everyday atrocities. Anne Frank, the teenager who had kept a diary while hiding from Nazis in Amsterdam, died there in 1945 at the age of 15.

In her op-ed last spring, Lewin wrote of the “unfathomable abyss” at Bergen-Belsen and the struggle to hold onto hope. She described a time when her father, beaten nearly to death by camp guards, asked her to hold a tin can up to his face so he could shave in the reflection.

“Many of his bones were broken, but he still wanted to maintain his dignity, to make a statement that his spirit could not be bowed,” she wrote.

Just before the liberation of the camp in 1945, the Hesses and several hundred other prisoners were loaded onto a train many suspected was headed to a camp with a gas chamber. The train, repeatedly delayed by bombing attacks, was known as the Lost Train. It meandered for 13 days through Nazi Germany before being liberated by Russian troops. Left behind at Bergen-Belsen were 13,000 unburied bodies.

***

Steven Hess asked a native Dutch woman and family friend in Rochester, N.Y., to translate Van den Berg’s story into English, and he and his sister were soon transported back to a time when everything but hope of survival was stripped away from them.

“To me,” said Hess, “it was a major miracle that out of a small fishing village, and as result of an article that crossed halfway around the world … I found out about so many missing parts of my history.”

Hess said he hadn’t known the nanny’s name before reading the article and had no clear memory of her.

“I remember her as a presence,” said Marion. “It’s kind of a blurry memory, and when I saw the picture, I didn’t immediately recognize her.”

The twins had always thought the costumes they wore in the photo were generic traditional Dutch garb. They didn’t know the clothes, or the nanny, were from Urk, a town they’d never visited. And they didn’t know the story of the photographer who took that photograph of them. Van den Berg tracked that down, too.

Leo Fisher, a member of the underground resistance, took photos for false ID documents that allowed Jews to escape the country. He was arrested the month after he took the photo of the twins. The very next day, he and 17 other prisoners were executed at gunpoint.

There was one more detail Van den Berg explored that resonated with Lewin. Before the family was ripped from its home in 1943, Karl and Ilse had left some of their most precious and valuable belongings with non-Jewish friends, hoping to reclaim them if they survived the camps.

After the war, Karl Hess went to retrieve his property and found that some of it had been sold during hard times by desperate families who hadn’t expected any Jews to survive. But a suitcase that had been filled with the Hess family’s fine linens and left in the care of the nanny was recovered by Karl Hess.

“We learned she had placed them under the bed and never allowed her children or anyone else to touch the package,” Lewin said. “After the war, they were returned in their original wrapping.”

***

The Hess family left Holland by ship late in 1946, steamed past the Statue of Liberty into New York Harbor and began to forge new lives. Karl Hess worked for textile companies, Ilse managed the twins, and the family endured, but not without lasting scars.

“My father in many ways was a broken man,” said Steven Hess.

“He made a decent living, was well dressed, lived humbly and life was OK. But he never spoke about the war,” Hess said. “I remember my father calling us together and saying, ‘We are Americans now, and we will speak English.’ Six months later, we never spoke Dutch again.”

Hess believes the family’s experience at Bergen-Belsen was much harder on the parents than on the twins, who were too young to comprehend the depths of depravity they were subjected to. But the children, too, struggled at times to adjust.

“For years and years, I could never fall asleep, because I thought if I fell asleep, I’d never wake up,” said Lewin. She says she kept bits of food at the foot of her bed, unable to let go of painful memories of wondering when she’d eat again.

“In some respects, I feel like I have been so lucky, and then there’s the burden of knowing you’ve had a blessed life,” Lewin said. “And there’s an almost daily thought of, ‘What about all those other people who were just as important and precious? Why did I survive and they didn’t?’”

Such thoughts motivated her to live a life of tolerance and purposeful work. Lewin is retired from a career in healthcare economics and policy in the Washington, D.C., area. Steven is retired from a career in photographic equipment manufacturing and distribution in upstate New York. The twins, born minutes apart and still in almost daily contact, each became parents and then grandparents.

Back in the Netherlands, Van den Berg found out that Marretje Pasterkamp worked as a nanny for another family after the Hesses were sent away. She married a pastry chef and grocer in 1946, and the couple, now deceased, raised their four children in the Amsterdam area.

Van den Berg says he may be retiring soon from the Zwolle Police Department, but his historical research and writing will continue. He said that in researching the Hess family story, he was motivated by his interest in World War II history, and by one more thing.

“Dutch police helped the Germans to arrest the Jews,” Van den Berg said, having explored the history of that time.

So was his effort, in part, a gesture of atonement for the failings of his predecessors?

“A little bit,” he said. “Yes.”

Lewin said that in the darkest moments behind barbed wire 75 years ago, there were those who risked punishment by caring for the sick and dying or helped find lost or stolen shoes for others. “It was all about maintaining hope in a dystopian world — looking to the light” and “remaining human,” she wrote in last year’s op-ed.

The op-ed crossed an ocean to the country of her birth, where a small-town police officer’s thoughtful research honored the lives of his subjects.

“I was touched,” said Lewin, who has held a couple of items from Holland in her possession for three-quarters of a century.

She still has two tablecloths and a set of dinner napkins from the suitcase that the nanny kept watch over while the family was imprisoned.

And she has an ashtray her mother gave to her father as a birthday present after the war. It’s made of black marble, with white veins running through it, and the engraving reads:

“Wij worden vanavond niet gehaald.”

This evening, no one will take us.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.