Mavericks explodes with ‘best waves in 10 years,’ pioneering waterman says

- Share via

The surf on Tuesday at Mavericks was “as good as it’s been in 10 years,” big-wave pioneer Jeff Clark said.

Clark ought to know. He was the first surfer to ride Mavericks, the formidable reef break west of the Pillar Point headlands. That’s at Half Moon Bay, about 25 miles south of San Francisco. Clark rode Mavericks for years before it became known in the early 1990s as the foremost big-wave surf break in the continental United States.

With surf in the 50-foot range, Clark said Tuesday was “an amazing day — the biggest, best Mavericks we’ve seen in 10 years.” There were 40 to 60 boats in the lineup, he said, and surfers from Hawaii to Portugal had traveled to Northern California to get a piece of the action.

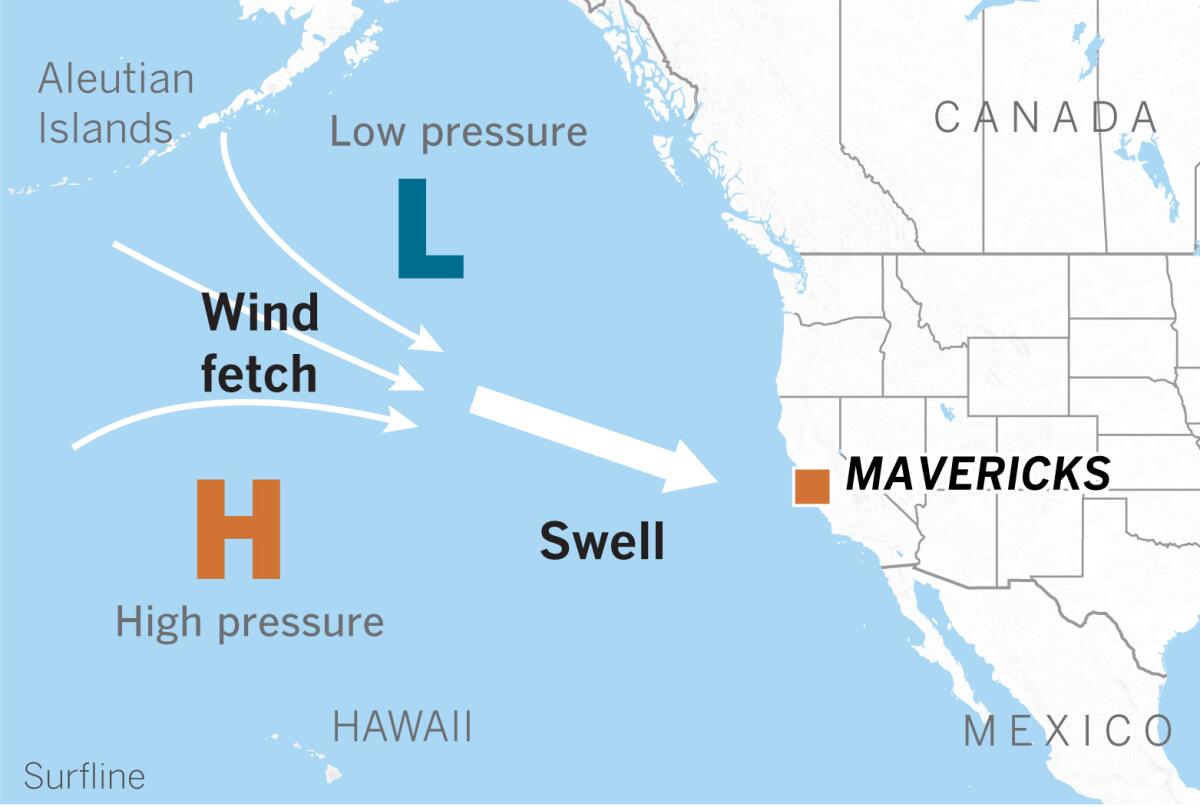

Surf forecasters had been watching a storm in the North Pacific that had pummeled Hawaii’s North Shore with big surf a few days earlier. Thanks to satellite technology, forecasters can predict a week in advance when swells will slam ashore around the globe.

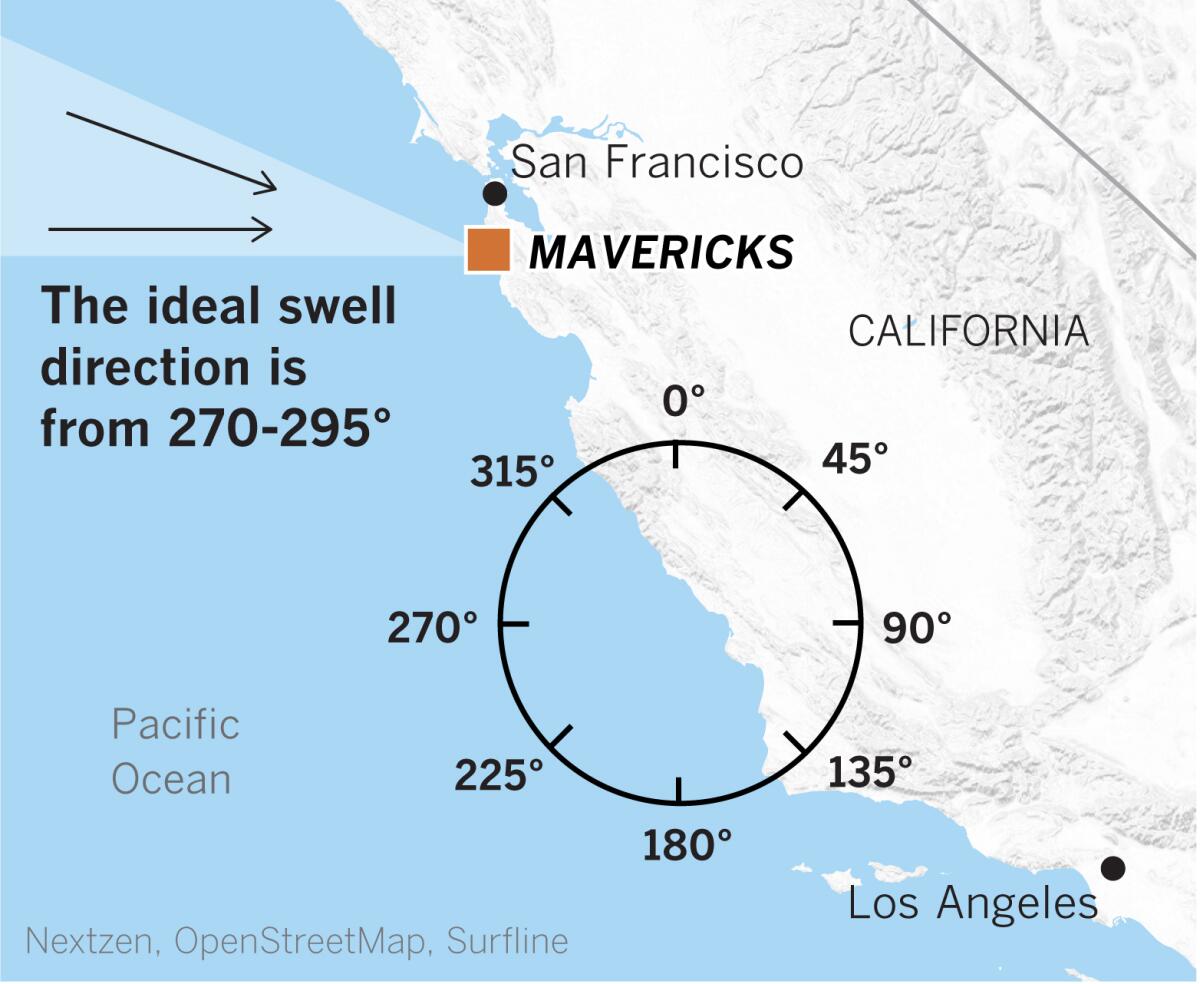

The swell direction on Tuesday was about 289 degrees out of the northwest. On a compass, 270 degrees is due west, and 180 degrees is straight south. The optimum swell direction at Mavericks, according to the surf forecaster Surfline.com, is 270 to 295 degrees. On a map, this swell window looks like a skinny sliver of pie. Imagine standing on the cliff overlooking the ocean and pointing due west. Now pivot to the north. Between those two imaginary lines lies the ideal swell direction for Mavericks. Going a little further to the northwest, from 296 to 301 degrees, you hit the wave shadow cast by the Farallon Islands.

The best season for surf at Mavericks is roughly October or November through March, with January being the peak month. These are the best months to get swells from the west or northwest of 8 feet or more with intervals of 15 seconds, according to Surfline. Mavericks begins to break at 10 feet, but generally needs to be at least 15 feet to show its stuff.

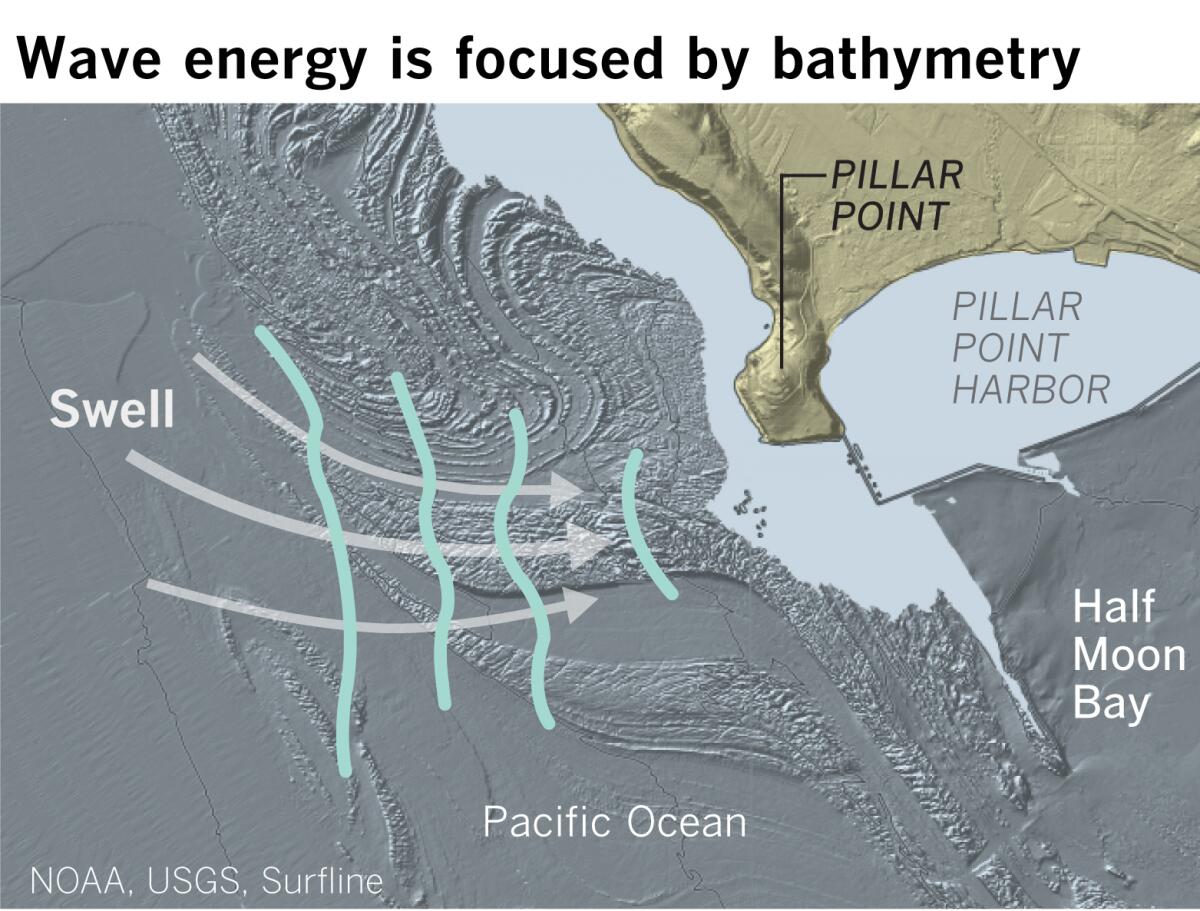

Winter is when mammoth storms in the Gulf of Alaska send swells toward the California coast. Mavericks is exposed to swells from the southwest too. This is the direction of swells primarily in the summer — which is winter in the Southern Hemisphere. These may also be large swells, but they don’t take advantage of the unique underwater topography, known as bathymetry, that focuses the waves from a west or northwest swell at Mavericks.

Swells are generated by winds from big storms, sometimes many thousands of miles away. The waves produced are dependent upon three main factors: the strength of the storm, its duration and the size of its wind fetch. The fetch is the length of open water over which the wind blows. The fetch is the part in which the energy is transferred from a storm’s powerful winds into the water.

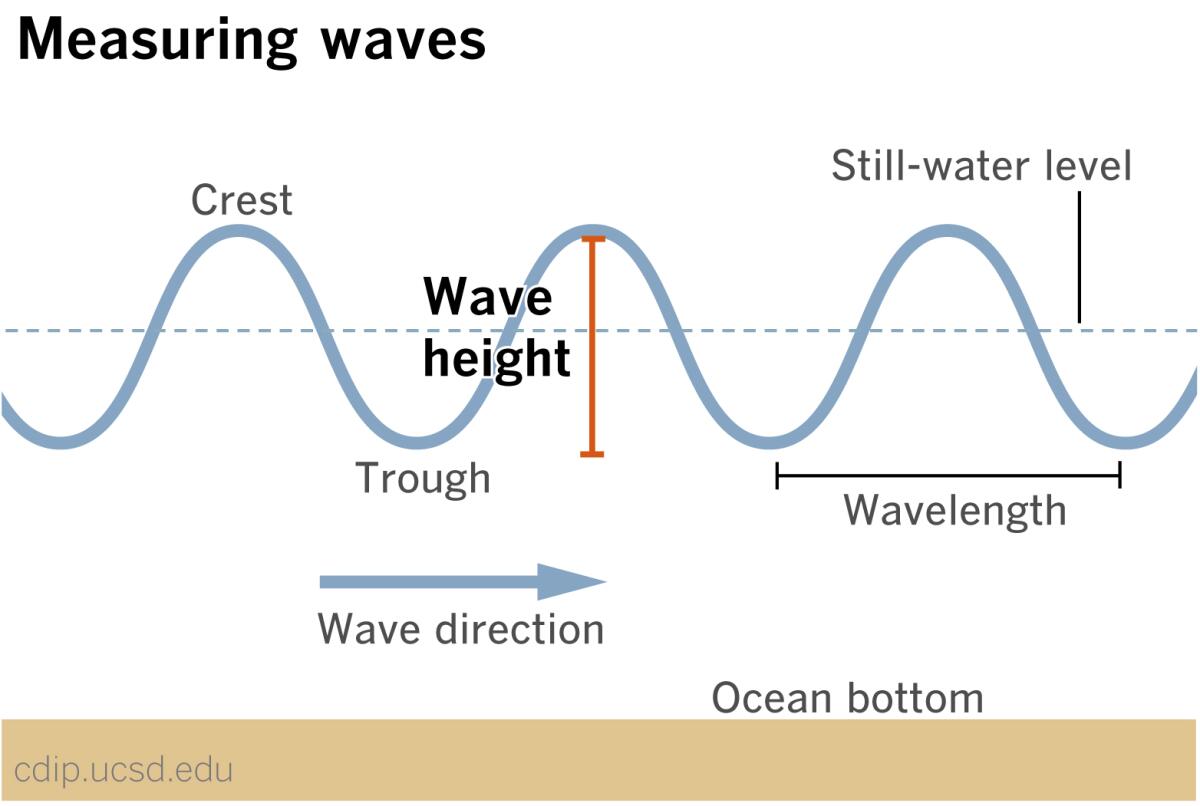

The waves with longer wavelengths travel faster. These are the longer-period waves that arrive first and illustrate the importance of accurate forecasting. These cleaner-breaking giants are the ones that surfers covet — the ones with more space between the crests — and are the waves that reward the surfers who arrive early. An interval of more than 16 seconds is considered ideal for Mavericks, according to Surfline. These longer-interval waves are also the ones with the most energy extending deepest beneath the water level, generating the unique Mavericks break. When these waves “feel” the ocean bottom as they approach shore, that contact causes the part of wave close to the ocean floor to slow down, and the top of the wave to accelerate, peak and eventually break.

This is also the point in which the unique swirling shape in the bathymetry off Pillar Point comes into play. Beginning about a mile offshore, the wave’s energy begins to be focused and magnified by a distinctive reef on the ocean floor. As the wave travels toward shore and it encounters shallower water over the reef formation, wave energy converges, lifting up monster surf.

Light offshore winds Tuesday along the Northern California coast helped to hold the waves up and keep them almost glassy, contributing to what Clark called “a perfect Northern California day.”

Clark started surfing at age 11, after his family moved to Half Moon Bay, and he says he surfed all the big waves in Northern California. In high school, he said, he carefully studied a wave breaking off Pillar Point. He did this from a perch high on the headland, where he could get a good view of the wave about a half-mile out in the ocean. Finally, after studying the wave for a long time, in February 1975, the 17-year-old Clark paddled out, braving cold water, treacherous currents and dangerous rocks. He continued to ride the wave known as Mavericks solo for 15 years.

One might think that the surf spot is named for the young maverick surfer who pioneered and conquered it, but it is actually named after Maverick, a white-haired German shepherd dog familiar to surfers of near-shore surf at Pillar Point in the early 1960s.

Clark introduced this new break to surfers from Santa Cruz and San Francisco in the early 1990s. Then, in 1992, the spot was presented to a worldwide audience with a cover story in Surfer magazine that, according to Matt Warshaw’s comprehensive “The Encyclopedia of Surfing,” described “the dark-haired, strong-jawed Clark as a ‘hellman,’ and the ‘unofficial guardian of a true secret spot.’”

Since then, a cascade of media attention and numerous surf videos and documentaries have given Mavericks and the surf contests held there global fame and recognition.

Tow-in surfing was introduced at Mavericks in 1994. With this controversial method, surfers could ride bigger waves when they were towed in behind a personal watercraft.

The wave that Clark rode alone for a decade and a half, beginning as a teenager, tragically claimed the lives of renowned Hawaiian big-wave riders Mark Foo in 1994, and Sion Milosky in 2011.

To what does Clark attribute his fearlessness during the years when he was the “Lone Ranger” at a dangerous, then-unknown Mavericks? “You’re bulletproof at 17,” he responded.

No local board shapers knew how to make surfboards to accommodate the waves Clark was riding, so Clark, a third-generation carpenter, taught himself to make his own. Clark now operates a surf shop and a paddleboard shop in Half Moon Bay, specializing in boards for Mavericks.

In a year so severely marred by a global pandemic and economic crisis, surfers received a gift from the North Pacific this week when weather and swell conditions aligned to provide a rare perfect day along the San Mateo County coast. And it’s just possible that there may be more swell on the way Sunday and Monday, Clark said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.