Column: Should Mayor Garcetti go to D.C. if Biden offers a job? When does the next plane leave?

- Share via

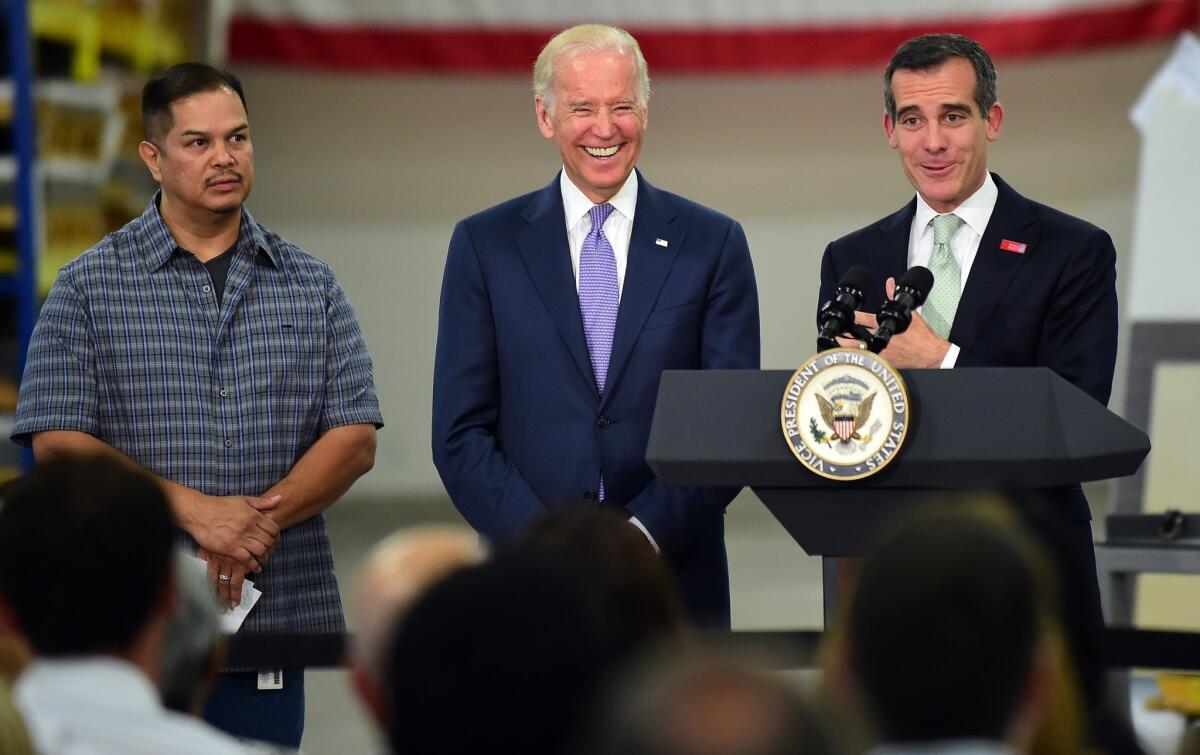

If President-elect Joe Biden calls Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and offers him a big job in the new administration, should the mayor go east?

If I were Garcetti, I’d already have my bags packed and a Washington condo lined up.

Garcetti served as national co-chair of Biden’s campaign and has been on a short list of candidates, possibly for Transportation secretary, because who wouldn’t tap the mayor of a city with notoriously bad traffic to bring his talents to Washington?

Biden and Garcetti have been largely mum, even as Biden has begun introducing his picks for key cabinet posts. And at the moment, there are two things we don’t know for sure.

Whether Biden will call.

And whether, if asked, Garcetti will leave town.

So let’s get into both of those, beginning with why I think Garcetti should grab any good offer from Biden like the life preserver it would be.

Sherry Bebitch Jeffe, a longtime observer of local politics, lays it out pretty well.

“Look at the mess we’re in,” she told me. “Wouldn’t you like to find a way out of this morass? I mean, there’s an increase in homicides, there’s the pandemic, and the issue of homelessness is always going to be around his neck.”

Exactly.

Garcetti has two years left in his term as mayor, and by some measures, the city’s fortunes over that time look bleak. Budget deficits will be a killer, thousands of city workers could get sacked, an economy wrecked by the virus could take years to recover and the city of tarps and tents is likely to see more of both on Garcetti’s watch.

Some have speculated that Garcetti’s calculation may be that it wouldn’t be right, or look good, to leave a job he was elected to while so much work remains to be done.

Yeah, maybe. But I doubt it.

Garcetti is good with words. He may already be in front of a mirror making a speech about what a true patriot does when duty calls — when there’s an opportunity to serve the needs of the entire nation as well as the city he loves, a city that hasn’t gotten its fair share of federal dollars.

He can also rationalize an early departure by noting that due to an election calendar change, his current term will run more than five years rather than the usual four, so he’s already approaching the normal finish line.

And besides, Garcetti is an ambitious man who always has one eye on what’s next, and there is no clear path for him to emerge from this sharknado of municipal distress with a brighter political future.

But will Biden extend an offer? Or would it look bad for the president-elect to begin his administration by hooking arms with a mayor whose city is in crisis, and whose homeless population has grown despite efforts by the mayor to raise and spend more tax dollars on solutions?

A mayor, by the way, who has found himself in the awkward position recently of saying he was unaware of inappropriate behavior by a former chief aide and ally who has been accused of sexual misconduct.

And is Garcetti, who has only held local office, qualified to run the federal department of transportation?

He wouldn’t be the first mayor to run that department, said Brian Taylor, director of UCLA’s Institute for Transportation Studies. Former Charlotte, N.C., Mayor Anthony Foxx had the job during the Obama Administration and former San Jose Mayor Norman Mineta ran the department under former President George W. Bush.

In Mineta’s case, though, he had been a congressman and ranking member of the House Transportation Committee, and Garcetti wouldn’t have the advantage of that experience. But Taylor said big-city mayors like Garcetti have to know how to pull federal, state and local resources together, along with political will, to get transportation projects moving.

“I would say, knowing Mineta a little bit and Foxx a smidgen, that Garcetti is probably more of a down in the weeds policy wonk than either one of them was,” said Taylor.

James Moore, on the other hand, director of USC’s Transportation Engineering Program, is rooting for Garcetti to get the job because he’d like to see him leave town.

“The man is a walking nightmare with respect to local transportation decisions,” said Moore, who argued, among other things, that Garcetti’s road diets — intended to make way for bikes and improve safety — have added to congestion and fallen short of the mayor’s promises on greater safety.

But Moore’s bigger criticism has to do with Garcetti’s role as a member of the regional Metro board.

“As board president and member he has cheerfully supported Metro’s cumulative, $26-billion-and-counting in expenditures on the rail system,” Moore says. The emphasis on rail, Moore says, has hurt bus service and “driven end-to-end transit trips per capita down by 40% from our 1985 peak.”

Personally, I’d like to see more east-west and north-south thoroughfares become dedicated bus routes, congestion pricing in dozens of traffic bottlenecks, financial incentives for not driving alone in a car and penalties for doing so, along with more of the telecommuting we’ve been practicing the last eight months.

But everyone’s got their own take, and Garcetti is not the king of greater Los Angeles, so he can’t be given full credit or full blame on any traffic and transportation issues. There’s the City Council involved, and the county board of supervisors, as well as elected officials in dozens of cities. And Garcetti hasn’t been without some victories, including his role in promoting years of transportation funding through voter-approved Measure M in 2016.

“Measure M will be a signature legacy,” said Juan Matute of UCLA’s Institute of Transportation Studies, with various infrastructure projects producing thousands of jobs for years.

Garcetti also touts his role on projects including the Crenshaw/LAX line, the Purple Line extension and the Gold Line Foothill extension and a conversion to clean-energy buses. And the mayor’s website promises to leverage Measure M “to complete 28 key transit and highway projects in time for the 2028 Olympic and Paralympic Games.”

For all that, Matute said he hoped Garcetti “would have had more success in the implementation” of his vision for a better Los Angeles, given the mayor’s grasp of the intricacies of transportation planning.

It’s kind of like that on homelessness with Garcetti, who has held local office now for nearly 20 years, most of it as either City Council president or mayor. He knows the nuances of policy inside out, but the homeless population continues to multiply, and prior to the coronavirus, so did the region’s commuting nightmares.

Building consensus on how to fix that isn’t easy, and it sure as heck won’t happen in the next two years, if ever.

Garcetti, who happens to be a former lieutenant in the U.S. Navy Reserves, is the captain of a ship that’s taking on water. He can remain at the helm and try to steer us away from the rocks, or he can start paddling east.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.