Catalina plans to import bison to boost the herd. Biologists aren’t happy

- Share via

Avalon — A recent announcement that the nonprofit that owns nine-tenths of Santa Catalina Island plans to boost eco-tourism by adding bison to existing herds has recharged a debate over the environmental impacts of the shaggy, imported beasts.

Locals cherish the bison as living symbols of the island’s heritage. Homes in the island’s close-knit community of 4,000 permanent residents are festooned with painted images of bison. Gift shops sell furry bison figurines. Catalina’s marathons are advertised under colorful bison logos.

The descendants of 14 bison left here in 1924 by a movie crew are also a powerful attraction for eco-tourists, roaming Catalina’s 76 square miles of rugged mountains, sweeping valleys, and grasslands, where the largest predators are island foxes the size of housecats.

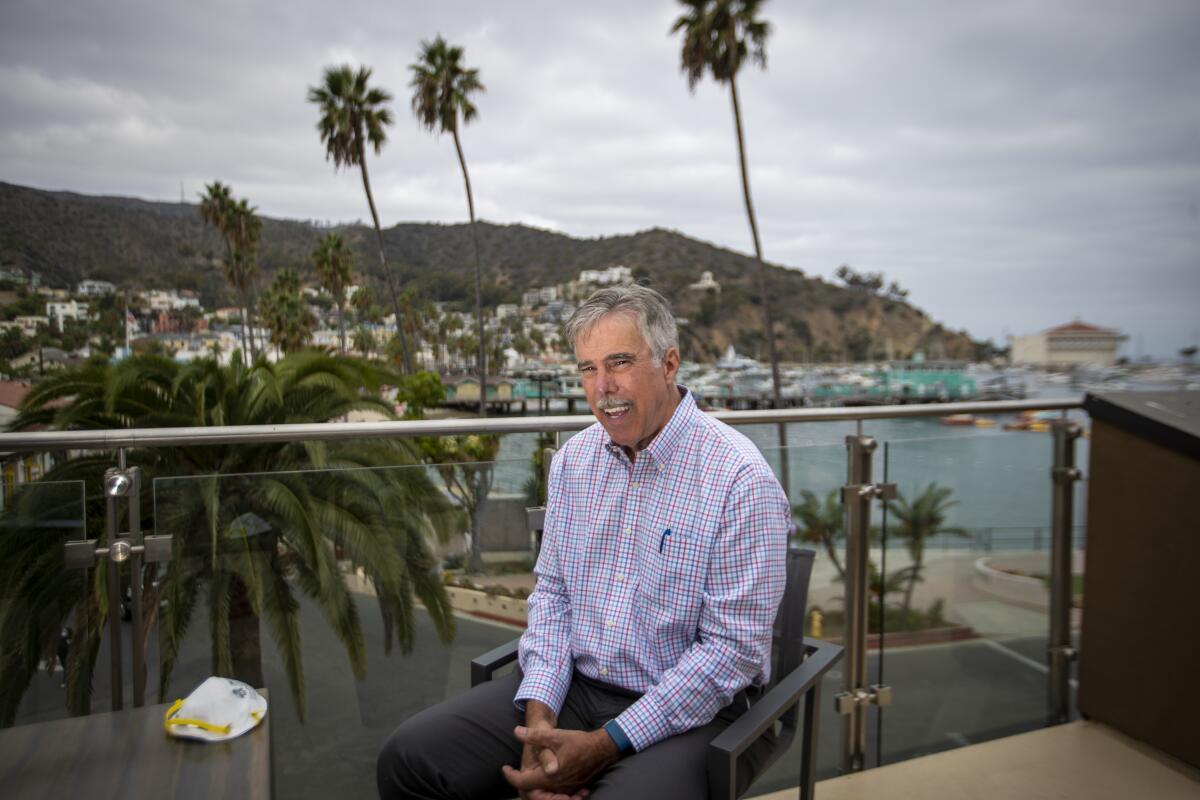

“The number one thing that tourists want to see when they come to Catalina is bison,” said Tony Budrovich, president and chief executive officer of the nonprofit Catalina Island Conservancy, “and people want to see them running wild rather in a fenced enclosure.”

Tourists can buy tickets for tours of the island’s interior at The Trailhead, the conservancy’s new $17-million nexus of nature exhibits, gift shop, restaurant and bar overlooking Avalon’s cozy harbor and cafe-lined promenade.

The Conservancy runs Naturalist-led Eco Tours from the Trailhead priced at $79 for a 2-hour tour and $119 for a 3-hour tour. Separately, the Catalina Island Company offers 2-hour “Bison Expedition” tours priced at $89.65 for adults and $85.49 for seniors and children.

The trouble is that catching a glimpse of bison has been increasingly difficult since the conservancy in 2009 launched an experimental $200,000, five-year program designed to limit the population through contraception. The goal: use inoculation to reduce herd size to a manageable 150 or so, which would be healthier and less environmentally damaging.

Reducing the herd had been recommended in 2003, when there were 350 bison on the island, by a scientific study that concluded that foraging and wallowing bison were trampling native plant communities, altering tree canopies by rubbing against tree trunks, and undermining weed management efforts by dispersing nonnative grasses through their droppings.

The survey also said that “although the bison seem to be doing well, they are significantly smaller than mainland bison, experience relatively low reproduction rates and appear to be in poor nutritional condition, based on blood tests and frequent observations of open sores.”

Conservancy officials said the health of the herd improved after the herd was reduced significantly in 2005 by sending some of the bison out for slaughter or to breeding programs elsewhere.

The program was led by former conservancy biologists Julie King and Calvin Duncan and lauded by island residents who had fiercely resisted earlier efforts to rid the island of nonnative goats and pigs.

It was supposed to have been reversible once the inoculations ceased. But there hasn’t been a calf born on the island in seven years, the conservancy said, and the herd size has dwindled to 100.

Now, the conservancy board is working with the Laramie Foothills Bison Conservation Herd to bring two pregnant female bison to Catalina Island, situated about 22 miles south of Palos Verdes Peninsula, in December.

As the sun rose over this harbor town, four scuba divers with cameras and notepads finned toward canopies of undulating kelp.

“We didn’t want to keep losing bison to the point where the herd wasn’t sustainable,” Budrovich said. “So we’re bringing a few animals over and allowing them to start having babies again.”

That was disappointing news for former conservancy consulting biologist Juanita Constible, who in 2007 spent up to 14 hours a day noting the massive, beady-eyed beasts’ every move and grunt. She was chased by the island’s main animal earth movers several times. She also understands how deeply important they are to the island’s residents, both culturally and economically.

Still, “I personally feel Santa Catalina has plenty to offer without bison,” she said, “and worry that the herd may face even more severe challenges in the future because of warming and drying trends.”

Duncan agrees. He also suggested that “Catalina’s bison remain in poor health and that may be contributing to their inability to produce calves. Blood analysis conducted as recently as 2015 revealed nutritional deficiencies, and there were observations of broken and brittle horns and emaciated individuals.”

Beyond that, he said, “Simply adding more bison will not result in more bison sightings.” That is because eco-tourism customers follow the same assigned routes each day, but the bison herds hang out on remote, isolated patches of grass as green and steep as anything in Hawaii, he said.

It’s not the first time the actions and tourism-oriented values of the conservancy have kicked up a controversy underlining a defining characteristic of its residents: a deep resistance to change.

Previous issues included a 2012 plan to raise funds for stewardship of the island by opening new tourist attractions including a proposed gondola ride from the Wrigley Memorial and Botanic Garden to a scenic ridgeline overlooking Avalon. The gondola never left the drawing board.

But critics suggest that the costs of importing and maintaining additional bison could have been better spent on projects designed to thin herds of mule deer — the most destructive species left on the island. The deer, whose population now stands at about 2,800, strip terrain of brush and saplings, leaving dry tufts of grass.

Budrovich acknowledged that some biologists are not pleased with the decision to grow the bison herd. But he said it is consistent with the vision that chewing gum magnate William Wrigley Jr. had when he bought up much of the island in 1919: a destination for people to enjoy in many ways.

“Our core missions are conservation, education and recreation,” Budrovich said. “These animals are important to the culture of the island.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.