Column One: At USC, 2 determined women spoke out. Ugly attacks over racism, anti-Semitism, Zionism took over

- Share via

They were born in different countries, with disparate cultures and faiths. But the two students shared a common dream to attend USC.

Rose Ritch, a San Francisco native, came to USC to study dance but soon widened her academic interests to sociology, law, history and culture. Socially, too, she thrived: winning election as student body vice president in February, nurturing her strong Jewish identity through the Hillel organization and Trojans for Israel.

Abeer Tijani left Nigeria as a toddler and grew up in a diverse Dallas suburb. With an interest in science, she ranked in the top tier of her class, played soccer and flute and served in student government. The achievements helped her land a full-ride merit scholarship to USC to study global health and social entrepreneurship.

The two women, both seniors, have never met. But their worlds collided this summer when Tijani launched an effort to impeach the then-student body president, Truman Fritz, and Ritch amid the national fury over George Floyd’s killing and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Tijani says she questioned Ritch’s commitment to fight racism. Ritch feels she was targeted because she supports Zionism — which she defines as belief in Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish homeland, but opponents see as an oppressive political movement that has displaced and discriminated against Palestinians on the land they also claim as home.

Both inside USC and beyond, their conflict grew into a fierce debate between free speech and hate speech, anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism. Jewish, Mideastern and Muslim organizations, along with scholars throughout California and the nation, weighed in, confronting USC with a flurry of dueling demands to acknowledge their stance.

Both women became targets of relentless, supercharged social media attacks they had unwittingly touched off. Ritch was shocked by the online vitriol. Tijani appealed for calm. But it was too late.

Ritch eventually resigned and in a Facebook post said she was hit with anti-Zionist attacks. Tijani said she felt endangered and scapegoated by the university in her stand for racial justice.

Their wrenching experiences reflect the personal toll caused by the complex and combustible conflicts over race, religion and politics sweeping college campuses throughout the country — and the difficulty that university administrators face in trying to manage them. When USC President Carol L. Folt expressed empathy for Ritch and condemned anti-Semitism this summer, she ignited another furor over the line between religious bias, political criticism and free speech.

But USC leaders are seeking a way forward this fall. Folt has asked the USC Shoah Foundation to expand its anti-hate program to the entire campus and has convened a new faculty group to propose how to better address anti-Semitism and Islamophobia.

In addition, university leaders declared that online hate and harassment are “totally unacceptable” and perpetrators would be held accountable.

“These expressions of online hate and harassment have targeted Muslim, Jewish, Palestinian, Black and other students,” wrote Winston B. Crisp, vice president for student affairs, and Varun Soni, dean of religious and spiritual life, in a letter at the onset of the school year. “This has caused profound pain for students who have been blamed and scapegoated for situations beyond their control.”

For Ritch and Tijani, the pain lingers. In a desire to be understood and move forward, they agreed to tell their stories.

How a campus dispute exploded

Ritch, captivated by dance as a child, studied ballet in New York and then joined a dance company in Arizona. But she yearned for a larger world. At USC, she found one. She met aspiring screenwriters and business majors. She observed Friday Shabbat with new Jewish friends.

Inspired by the work of student leaders — lobbying for a fall break, for instance — she accepted Fritz’s invitation to be his running mate. Last February, the pair was elected to the top two student government offices on a platform to increase diversity, sustainability, administrative accountability and health and wellness services.

“We wanted to make [USC] a more inclusive, welcoming, accessible place,” Ritch said.

At the time, Tijani — a lover of cultures who speaks three languages — was studying abroad in Spain to perfect her Spanish and take classes about the European Union.

When the pandemic hit in March, USC brought all students back. Tijani said she was “just livin’ my life” — until May, when Floyd was killed.

“I was sick to my stomach,” she said. She compiled a resource list for antibias education and spoke out about racism in videos, articles and campus Zoom panels.

In late June, Tijani noticed a new Instagram account, @black_at_usc, where anonymous Black Trojans described racist treatment by faculty, police and fellow students — as Black students at other colleges and high schools have begun to do. Four posts particularly caught her eye: They said the student body president, whom they did not name, had made Black students uncomfortable with his jokes, remarks about the “pains of being white” and requests to turn out the Black student vote, which many Black Trojans perceived as a stereotype.

Tijani looked up campus articles about the election and felt that Fritz and Ritch had not chosen a fully diverse leadership team — further reason, she said, to question their commitment to racial justice.

She sent Fritz an email in late June, asking about the posts and how he and Ritch proposed to lead the student body at a time of such painful racial reckoning. Fritz did not respond directly to her but posted an Instagram statement that day, saying he recognized he was a “person of privilege,” asked fellow students to help educate him about race and announced plans for greater outreach to diverse student groups.

Ritch did not respond. She said she was working and off her social media when the exchanges occurred. Unsatisfied by Fritz’s response, Tijani announced on Instagram that she would pursue their impeachment because they “do not authentically represent nor promote the true breadth of diversity that our community has to offer.”

In listing the grounds for removal, Tijani asserted that Ritch had aligned herself with Fritz’s “privileged gatekeeping” and failed to provide a check on him. She also said Ritch had not maintained a strong relationship with the student body, as campus bylaws required, because she had been “outspoken on issues that alienate Palestinian Trojans” without elaborating.

And that’s when things blew up.

Social media posts began calling for Fritz and Ritch to step down — referring to her as a “Zionist.”

By the next day, Tijani was alerted by friends that Ritch was being slammed on social media. She was appalled, she said, and immediately spoke out.

“I want to make it very clear that I do not condone anti-Semitic sentiments of any kind,” she posted on Instagram. “I do not and WILL NOT stand for any ... attacks on her identity. I also want to make it very clear that I am fully in support of Palestinian students on campus feeling safe and feeling able to voice their concerns. Being Pro-Israel is not an impeachable offense, just as being pro-Palestine is not an impeachable offense because we must all be allowed to have our rights to freedom of speech protected.”

But her words failed to stop what was to come.

“The tiger was let out of the cage,” said Dave Cohn, director of USC Hillel, a nonprofit that supports Jewish students. “It was like a dog whistle to a whole group of people.”

Ritch continued to be bombarded with hateful messages. Dirty Zionist. Anti-Palestinian. Racist. Trash. One called her a “Zionist ass VP” who needed to resign, according to social media posts compiled by the Louis D. Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law. Within 12 hours, Ritch said, she deleted her Instagram.

“It was just flooding in, and on Twitter, and it was just going crazy,” she said.

She was shaken and scared, worried about returning to campus. The hostility was new to her.

“It’s highlighted how with great speed and ease a great deal of pain and discomfort can be created by how views are expressed in social media environments ... that undermine students’ sense of security and support.”

— Dave Cohn, director of USC Hillel

USC has had a history of anti-Semitism, particularly in the 1930s and 1940s, by such prominent campus figures as former university President Rufus von KleinSmid and former coach Dean Cromwell, according to Steven J. Ross, a USC history professor.

Ross, Cohn and Ritch herself said USC is now a comfortable campus for Jews. Ritch said she never thought twice about wearing her Star of David necklace on campus or putting out recruiting tables for Trojans for Israel, despite the occasional student who would walk by and criticize the Jewish state’s treatment of Palestinians.

The summer furor was exacerbated by a parallel controversy involving a USC student senator, Isabel Washington. She stepped down July 1 after outcry over anti-Palestinian statements she posted on social media, which the Undergraduate Student Government body criticized in a statement announcing her resignation.

The months of high-profile attacks set nerves on edge for many Black, Palestinian and Jewish students.

Cohn said some Jewish students began reaching out to him for the first time about whether the campus was safe for them.

“It’s highlighted how with great speed and ease a great deal of pain and discomfort can be created by how views are expressed in social media environments ... that undermine students’ sense of security and support,” he said.

Ritch reached the breaking point and went public with the anti-Zionist attacks against her in a Facebook post.

“The people with whom I have shared a campus with for years, the people whom I desperately want to serve, have tried to make me feel ashamed, invalidated, and dehumanized because of who I am,” Ritch wrote. “My Zionism should not and cannot disqualify me from being a leader on campus, nor should others presume what that means about my position on social justice issues. What happened to me is wrong and unjust, and now it is my turn to make sure this never happens again.”

The post did not mention Tijani, but her name was easy to find. Suddenly, Tijani said, she was hit with “disgustingly racist messages” and accusations of anti-Semitism. Her name, photo and social media accounts were plastered over the Internet. She felt in danger, she said, and worried about her safety and future.

“I felt hurt. I felt scared,” Tijani said. “That was just kind of the beginning of this false branding of me being the ringleader for some anti-Semitic campaign against Rose.”

The two women have never directly spoken with each other. But Jaya Hinton, co-director of the USC Black Student Assembly, said she spoke to both Tijani and Ritch and that neither ever intended to hurt the other. She blamed the furor on the way social media propels misunderstandings “to take on a life of their own.”

Hinton added that Black students were frustrated by the online attacks on a Black woman “who does not have an ounce of hatred in her heart.”

In an interview with The Times, Fritz, the former student body president, denied the allegations of microaggressions.

For her part, Ritch explained in an interview that her love for Israel does not preclude compassion for Palestinians, having visited the West Bank and personally heard “heartbreaking” stories in conversations with them about their difficult lives. She said she supports a homeland for both and rejects a binary choice between the two.

Fritz and Ritch publicly condemned racism and supported summer events to stand with the Black community after Floyd’s death.

But they never shared that information with Tijani, who had tried to set up meetings to hear them out before filing her formal impeachment documents. The petition was supported by several other student government cultural organizations and focused on what they saw as the leaders’ lack of support for Black Trojans, making no references to Ritch’s Zionist beliefs or Jewish heritage. Ritch and Fritz said they were uncomfortable that she wanted to record the meeting to post on social media — which Tijani saw as an accountability measure for elected student leaders and they perceived as a barrier to open and candid conversation.

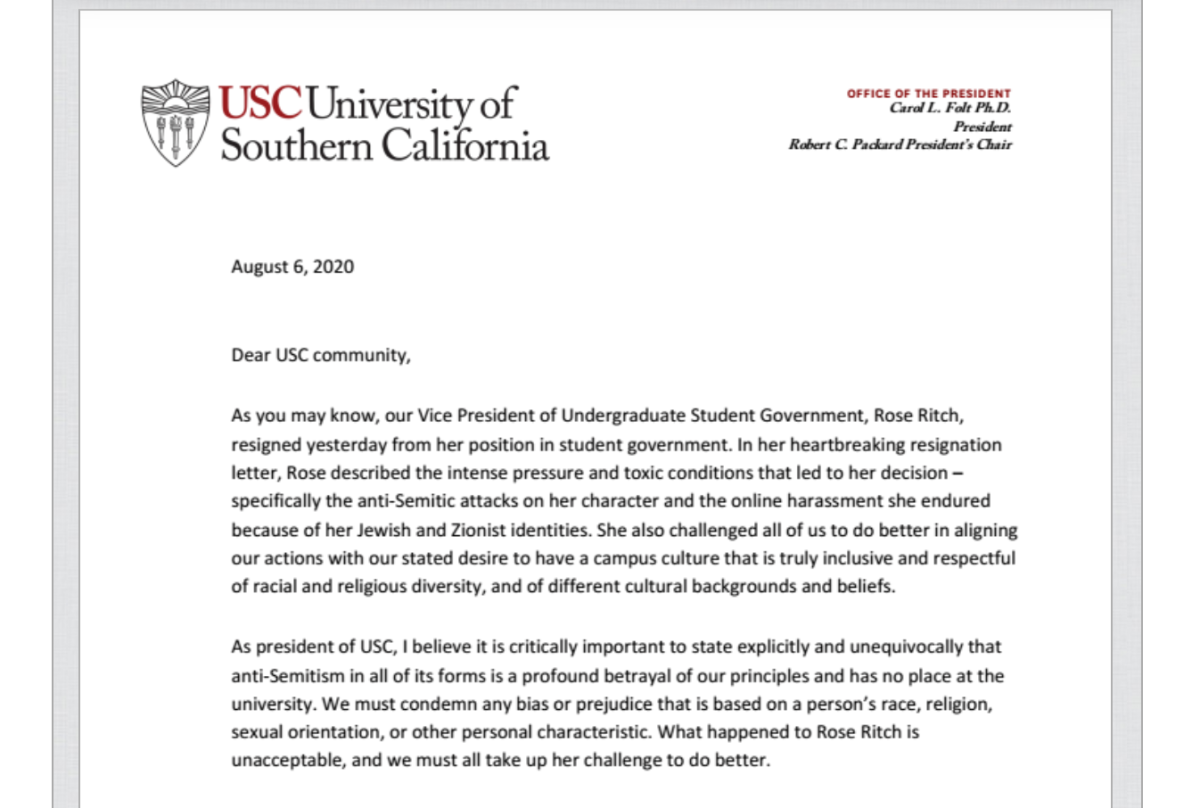

The Folt letter

Meanwhile, Folt was being pressed to take a stand. In an open letter, prominent USC Jewish faculty decried Ritch’s treatment, while the Simon Wiesenthal Center and the Brandeis Center called on Folt to reject anti-Semitism. Folt did so the day after Ritch announced her resignation, decrying the “harassment she endured because of her Jewish and Zionist identities.”

“As president of USC, I believe it is critically important to state explicitly and unequivocally that anti-Semitism in all of its forms is a profound betrayal of our principles and has no place at the university,” Folt wrote in an Aug. 6 letter. “What happened to Rose Ritch is unacceptable, and we must all take up her challenge to do better.”

But Folt’s letter set off another furor, deepening the layers of the conflict and zeroing in on yet another heated dimension: free speech on college campuses. Controversy over whether criticizing Zionism and Israel’s treatment of Palestinians is acceptable free speech or anti-Semitic behavior has roiled many campuses, including UCLA, UC Berkeley and UC Irvine.

At USC, critics of Folt’s letter saw it as inaccurate and one-sided. Emad Askar, a senior in public policy whose family had lived in Palestine for generations until leaving three decades ago amid volatile clashes with Israel, said the USC president had wrongly conflated anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism.

Jewish Voice for Peace-LA, the Council on American-Islamic Relations-LA, the Middle East Studies Assn. of North America and California Scholars for Academic Freedom, which represents more than 200 faculty members at universities and colleges statewide, have all urged USC to affirm free speech, including the right to criticize Zionism.

They said no one took aim at Ritch’s Jewish faith; only her support of Zionism, which they argue is a fair topic for political criticism — especially in what should be a university’s open academic climate.

Ritch, Cohn and other Jewish Zionists, however, say that many Jews see their support of a Jewish homeland in Israel as a fundamental part of their cultural and religious identity and feel that attacks on Zionism amount to anti-Semitism. The Amcha Initiative, a nonprofit that combats anti-Semitism on college campuses, says that certain criticism of Israel can and has led to hostility and hate against Jewish students.

“We’re not going to do it anonymously on social media. We’re going to have those conversations in the open as grownups should do. And we might disagree at the end of it, but we’re going to disagree respectfully.”

— Stephen Smith, executive director of the USC Shoah Foundation

For Tijani, the impact of Folt’s letter was far more personal. The letter did not mention Tijani by name, but the student had wanted Folt to publicly acknowledge her explicit rejection of anti-Semitism and that her impeachment effort was rooted in concerns over racial justice and the accountability of elected student leaders. But neither the letter nor Ritch’s resignation statement included that important context.

“She essentially was helping put a target on my back,” Tijani said of Folt.

Folt did not respond to questions about her letter, but Crisp said it was “regretful” that its intent to condemn bullying against not only Ritch but all students had not been effectively conveyed.

“I do understand people feel that it was one-sided and it didn’t cover everything that people would want it to cover,” he said, adding that the letter did meet its purpose of declaring that a student’s identity should not be a disqualification for campus leadership positions.

“I want to be clear that there is no place for bullying and harassment and the kind of hostility that our students are facing, whether we’re talking about Rose or whether we are talking about Abeer or any other students,” Crisp said.

Moving forward

As the academic year unfolds, USC is launching new initiatives to help the campus better handle racial, religious and political strife. The USC Shoah Foundation, which harnesses the power of testimony from genocide survivors to develop empathy, understanding and respect, plans to sponsor “critical conversations” on these sensitive topics. A discussion about anti-Semitism at USC is set for Monday, followed by forums on Islamophobia, racism and an all-student panel on “The Pain of Hate: Life at USC.”

“We’re not going to do it anonymously on social media,” said Stephen Smith, the foundation’s executive director. “We’re going to have those conversations in the open as grownups should do. And we might disagree at the end of it, but we’re going to disagree respectfully.”

In addition, a new faculty group is working on ways to help the campus better address anti-Semitism and Islamophobia and understand how they intersect with academic freedom, free speech, identity and inclusion.

As for Tijani and Ritch, both students remain unsettled. But they say the ordeal has changed and strengthened them.

Ritch said she is now terrified of social media. “I think of Instagram and my stomach starts to hurt,” she said.

But she is engrossed in her internship with a U.S. congressional candidate’s campaign and aims to find a job in politics or lobbying in Washington, D.C., after graduating next spring. Her love of Judaism and her Jewish community has deepened. And she is stronger, she said.

“Being able to see I was able to get through this has given me a little more confidence in my strength as a human being,” she said.

Tijani is still frustrated that her initial aim to address racism was overshadowed by a debate over anti-Semitism; she feels both conversations can and should be held concurrently. But she said she has learned to defend herself — she now aspires to become a human rights lawyer — and hopes her experience will give other marginalized students the courage to speak out about their deeply held beliefs and prod USC to better protect them when they do.

“I’ve moved on,” Tijani said. “In the same graces that a lot of Black women have to find peace within themselves, because the world will not offer it to them, I’ve found peace and healing within myself.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.