Volunteers who help kids in foster care are wanted more than ever during the pandemic

- Share via

This is the story of a beautiful little girl, now 9, who loves princesses and unicorns and got a rough start in life.

Her mother tested positive for drugs when she gave birth.

She lived with her father, cared for by his mother, until her grandmother died.

After that, no one vigilantly tended to her needs, though she was only a toddler. No one signed her up for school when she was old enough for pre-K.

At 5½, she was removed from the care of her family by a social worker and police, and placed in the first of several foster homes.

Stories like this one often gather sadness as they go. Children rescued from hardship often face more as they bounce through an overburdened system, rarely receiving undivided attention.

But that isn’t this little girl’s story.

This is a story about what can happen when serious attention is paid — about how it can change a life’s course.

Such labor-intensive support is always in critically short supply. And it’s needed now more than ever as the COVID-19 pandemic makes those who are most vulnerable more so.

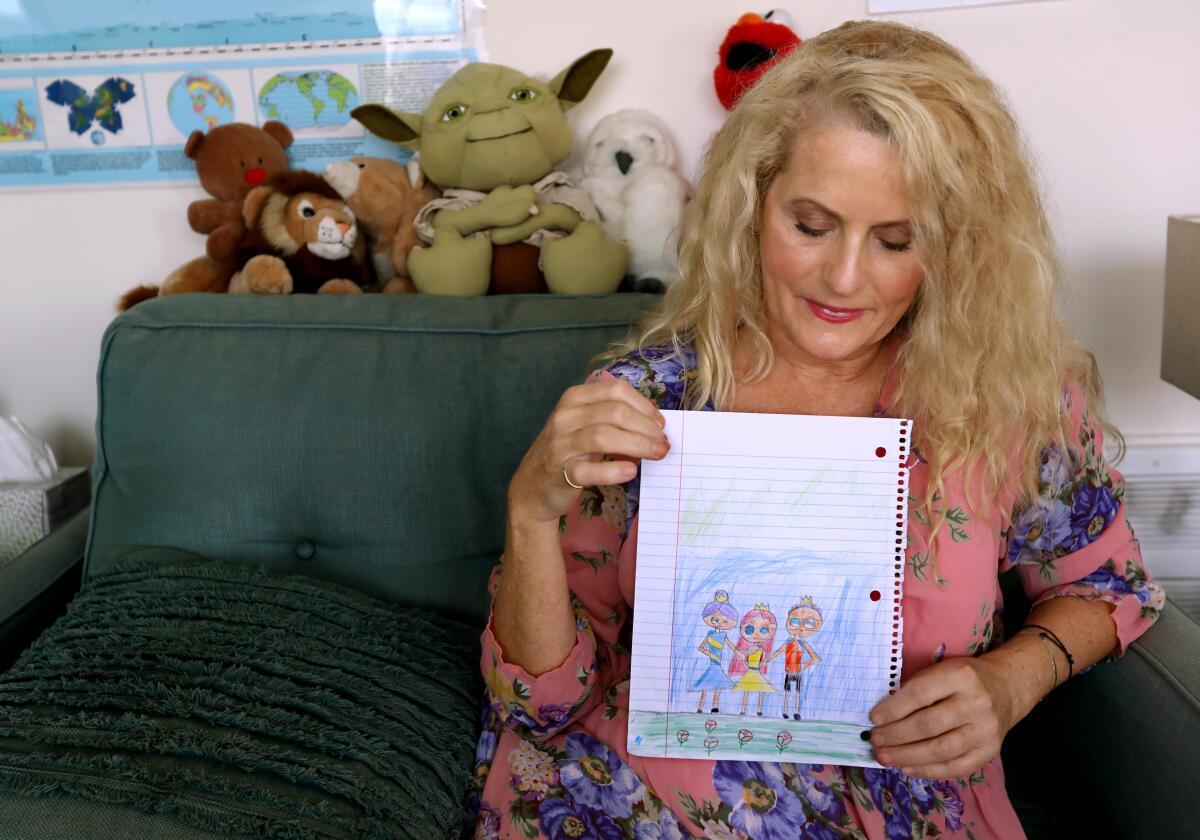

The little girl, who I’ve been asked to call Stefanie, though that isn’t her name, was in her second foster home when she met Jayne Amelia Larson, a volunteer for CASA of Los Angeles, who had been assigned to her case.

The nonprofit recruits and rigorously trains volunteers to champion individuals in the child welfare system — from newborns to 21-year-olds — who have been abused, neglected or abandoned.

CASA stands for court-appointed special advocate. A CASA serves as a sworn officer of the court, whose duty is to represent and ardently advocate for one particular child’s or young person’s best interests. Others — the social workers, attorneys, the judge in the case — have extraordinarily heavy caseloads. An L.A. judge might be overseeing more than 1,000 cases at one time, and the social workers and attorneys, hundreds, said CASA’s Chief Executive Wende Julien.

A CASA usually is focused on keeping track of every detail — and every possible way to help one person — in just one case.

This means poring over records: court files, educational, medical. It means working to form a strong one-on-one bond. It means keeping in touch with relatives, friends, teachers, social workers and attorneys to build the fullest understanding of their person’s circumstances. It means attending court hearings and writing periodic reports to the judge handling the case, offering the most complete, objective account possible of their person’s past life and current life, and problems, progress and needs.

It was the desire to get that full picture in order to make the best decisions, Julien told me, that led a Seattle judge to create the CASA system more than 40 years ago. L.A. soon followed suit. CASA programs are now in place nationwide.

I’m hard-pressed to think of a more serious — or potentially heroic — volunteer commitment. And I’m awed by the fact that in the L.A. area, more than 1,000 people have made it.

But great need remains. L.A. County has more than 30,000 open child welfare cases, Julien, said, and CASA estimates that around 12,000 of those are in desperate need of its services.

The Stefanie that Larson first met was deeply unhappy, often angrily acting out. She’d been removed from her first foster home because she fought the other children. Few in her family home had modeled appropriate behavior. Few in her life had offered her the attention she craved.

And here came this unicorn and princess combined.

“I said to her, ‘I am your CASA and I work for you. I don’t work for anybody else. I am your advocate. That means I’m your voice. And I work for you,’” Larson told me. “She said, ‘You work for me?’ And I said, ‘Yes, I work for you — and only for you. And that thrilled her.”

Stefanie had started first grade far behind her peers.

“She did not know how to hold a pencil or write one letter. She did not know hat or cat,” said Larson, an actor, writer and producer who was the ninth of 10 children but didn’t have kids of her own.

She had volunteered for years in arts-focused programs for at-risk kids and had learned about CASA after working with Peace4Kids, a nonprofit that gathers kids in foster care together each weekend.

“I just knew that I could do more for one kid than what I was doing on Saturdays,” she told me.

The Los Angeles Public Library’s buildings remain COVID-closed. But in the pandemic, librarians’ creativity has blossomed online and many new doors for patrons have opened.

With Stefanie, she got to work fast. Stefanie’s foster parent was struggling to get her extra help at school. Larson “went in like gangbusters,” she said, and demanded the individualized education plan, or IEP, the child needed. In signing up to be Stefanie’s CASA, she’d also taken on the extra responsibility of serving as her education rights holder — which gave her the power a parent would have to make educational decisions on her behalf. About 40% of CASAs also take on that role, Julien said.

Stefanie’s IEP, Larson said, “gave her a huge leg up in terms of resource teachers. She got extra attention. She got individualized attention. She was called out into smaller groups so that the teachers could see what needed to be developed. And she immediately started to do better.”

Because she had behavioral problems, she also was assigned a behavioral therapist, who worked with her in school. “She learned you don’t stab kids with a pencil when you get mad,” Larson said.

CASA’s ultimate goal is reunification with families if that’s safe — or, if not, other caring relatives or foster parents ready to adopt.

In Stefanie’s case, a social worker had identified a cousin in her early 20s who was considering stepping up, though the process was unfolding slowly. Larson pushed it forward, offering the cousin resources and information and support.

I was lucky enough to get to talk to that cousin, who asked that I use only her first name. Aileen was able to tell me many of the details I’ve shared about Stefanie’s background that CASA, because it is an open case, was unable to divulge. Aileen’s uncle is Stefanie’s paternal grandfather — who wanted more for the child after his wife died but worked long hours and could not get his own son to do better.

Aileen’s mother, already raising a granddaughter, tried to take Stefanie in but wasn’t approved. So Aileen began to try, even though she knew doing so would upend her life. She started visiting Stefanie in foster care and taking her out for adventures. Stefanie spent much of that time anxious about having to go back.

“If I was in her place and I needed help, I would want someone to try,” Aileen told me.

So Aileen and her longtime boyfriend, Yobani, rented a house and started readying it, preparing a pink room with princess sheets for Stefanie, meeting child-proofing requirements, jumping through hoops to be approved. Aileen took parenting classes, learning about good discipline and the effects of trauma, and opened her home for surprise inspections. Meanwhile, Larson asked the judge first to let Stefanie spend weekends and then longer stretches there.

Stefanie moved in with the couple nearly three years ago. “I was really happy because I knew she was going to have a place she could call home,” Aileen said. “I kind of felt that great feeling like when you graduate from high school.”

Stefanie calls the home “her safe place,” Aileen told me. She went from hiding the last crumbs of snacks in their wrappers under her bed to understanding that what she had was secure.

She moved to a great new school where, with Larson’s help, she received ample support. Larson provided books and flashcards. Aileen, whom Stefanie soon started calling Mommy, read with her every day. Before long, she had come up to her grade level.

And Larson was always there to push for more help for the fledgling family, getting the court to approve extra services and enrichment classes. When Stefanie got dance classes, Larson took her shopping for outfits and shoes, using a fund set aside within CASA to buy things for children in need. “She just ran around the store squealing with delight,” Larson said.

COVID threatened to undo the progress. Distance learning is hard for Stefanie, but Larson and CASA got her tutors and a donated used iPad. Then Aileen, who was serving takeout food, caught the virus, followed by Yobani and Stefanie. At first, Stefanie was “petrified,” Yobani said, that Aileen would die. But he, Aileen and Larson — known to the family as Jaynie — reassured her.

Clemencia Morales from Guatemala just became a new U.S. citizen. She’s been thanking America by making thousands of masks and big pots of food to give out for free

Larson had food delivered to the family when they were sick. She pointed them to extra financial resources. They recovered.

Larson and Stefanie talk via FaceTime frequently. Lately, Larson has been giving Stefanie acting classes and going with her to swimming classes — and they’ve been planning a fashion show.

Yobani told me he didn’t have words to describe Larson’s presence in the family’s life. He called her “our guardian angel.” And he told me about the very happy child he now lives with, how they discuss their lives at the dinner table every night, how his heart opened up twice over at Stefanie’s expanded horizons when she recently asked if she could still live with them when she went to college.

Stories like this one are never simple. After the judge terminated parental rights for Stefanie’s biological parents, her long-absent mother appealed. But Larson and CASA and Yobani and Aileen are there for whatever happens.

The pandemic and this year’s protest movement grew awareness of inequality and injustice. “People are wanting to do something that has an immediate impact on bringing justice to a person who’s experiencing injustice — and boy do our kids experience injustice at an extraordinary rate,” Julien told me. That, and the extra time quarantining gave some people, led to a nice surge in new CASA volunteers since March. Keep them coming.

This is a story about a beautiful little girl now receiving constant and unwavering support — and about the need to create many more such stories.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.