How the Bobcat fire grew into a unique menace that’s evading firefighters

- Share via

More than a week after the Bobcat fire ignited in the rugged terrain of the Angeles National Forest, it has emerged as an unusual menace that has evaded fire crews and threatened local communities — despite burning no homes and causing no injuries.

The fire has contributed to days of terrible air quality in Los Angeles, with residents reporting “mesquite-like” smells and a “powdery layer of haze” amid smoke advisories from the South Coast Air Quality Management District.

It also has managed to outwit firefighters, even in the absence of powerful Santa Ana winds that failed to materialize as predicted last week. Instead, officials say, the Bobcat fire’s power lies in two factors: its location and an inadequate supply of firefighters.

But climate experts warn there are larger factors at play.

“This fire was man-made on many levels,” said Bill Patzert, a climatologist who spent several decades at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge.

To understand why so many fires are burning out of control in the West, you have to go back to Labor Day — and the freak snowstorm that hit Colorado.

Record heat, population growth, fossil fuels and other factors related to climate change have contributed not only to the state’s unprecedented fire season, Patzert said, but also to the particular challenges of the Bobcat fire.

“It took decades to build this disaster,” Patzert said. “This didn’t come out of nowhere.”

By Monday night, the fire had burned more than 38,000 acres, according to the U.S. Forest Service, and the containment level dropped from 6% to 3%.

“It has been evasive,” Angeles National Forest spokesman Andrew Mitchell said Monday. “Where we’re trying to catch it, it’s still jumping out a bit.”

Containment estimates for the blaze have been pushed back by two weeks, to Oct. 30, much to the disappointment of residents in the nearby foothill communities. Parts of Pasadena, Altadena, Monrovia, Bradbury and Duarte have been contending with evacuation notices for more than a week, while some neighborhoods in Arcadia and Sierra Madre were ordered to evacuate Sunday when winds shifted.

“It’s completely terrain-driven at this point,” Mitchell said. “The area where the fire is situated hasn’t burned in 60, 70 years.”

That decades-long buildup of dried vegetation can act as fuel for a hungry fire.

“Here’s the ecological bottom line,” fire ecologist Richard Minnich said. “The more burns in a given area, the smaller and more manageable fires will be in the future.”

The blaze has also changed direction several times. Last week, it appeared to be moving deeper into the northeastern portion of the forest. On Monday, it was creeping south and west again, toward Mt. Wilson and the Chantry Flat area in Santa Anita Canyon.

One area of deep concern is the 116-year-old Mt. Wilson Observatory.

“While we hope the Observatory makes it through relatively unscathed, the battle could go either way,” Sam Hale, chairman of the Mount Wilson Institute Board of Trustees, wrote Monday. “We cherish the historic telescopes on the mountain that revolutionized humanity’s understanding of the Cosmos and hope they will be safe.”

Record heat. Record acres burned. Sky-high air pollution. The extremes California has experienced in recent weeks all have one thing in common: They were made worse by climate change.

David Cendejas, superintendent of the complex that houses 18 of the observatory’s astronomical wonders, watched as flurries of ash fell like snow Monday afternoon. He and several other staffers spent the morning introducing more than three dozen firefighters to the emergency systems and backup electric generators strategically located on the property, which is perched on a 5,710-foot mountain shaded by pines and oak forests.

They included a water tank connected to a high-pressure pump built in 1970 and last used when the observatory was rescued from the snarling flames of the Station fire in 2009 after a firefight that lasted five days and four nights.

As billowing columns of smoke turned the sky orange and gray Monday afternoon, firefighters in 12 engines were girding for the arrival of the flames, which would trigger a screeching blare from large horns on the observatory’s gleaming white dome.

“We’re not going anywhere,” Capt. Keith Stires with the Los Angeles County Fire Department said. “We are committed here.”

Beyond the worried neighborhoods and beloved observatories, the Bobcat fire is threatening the Cogswell Dam, which along with San Gabriel Reservoirs in the San Gabriel Mountains above Azusa is providing water for firefighters. On Monday afternoon, flames also were approaching the Santa Anita Dam, less than a mile above Arcadia.

“We’re approaching winter storm season, and that infrastructure is critical to protect downstream communities from potential flooding,” said Kerjon Lee, a spokesman for the agency.

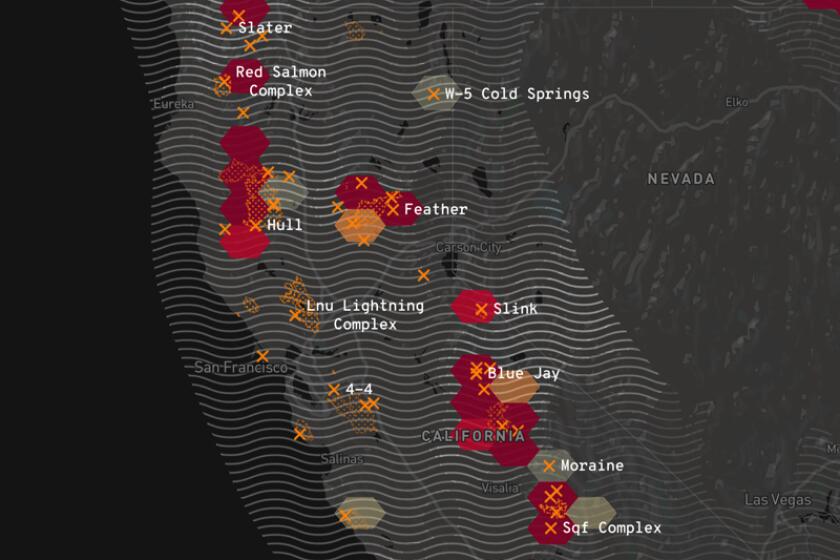

The Bobcat fire is one of more than two dozen blazes burning in California, and resources are stretched thin. Although nearly 900 personnel have been assigned to the fire in the San Gabriel Mountains, officials say it isn’t enough.

“The amount of personnel we have is very low for this size of fire,” Mitchell said. “And we’re spread thin throughout the state.”

Patzert said that although fire has always been part of the natural ecology of California, mass migration to the West Coast led to the development of areas that might otherwise have been less populous. (The state’s population has nearly quadrupled since 1950, according to the Public Policy Institute of California.)

“We’ve moved into areas where classically, we never built, because they were burn zones,” Patzert said. “When you create this great megalopolis of 20 million people [in Southern California], you create your own heat.”

Last month proved to be the state’s hottest August on record, and temperatures have spiked even higher in September.

“We were set up for fire up and down the entire state,” Patzert said. “Northern California had a dry winter, and these heat waves in August really set us up. It just dried everything out.”

Conditions were so ripe for ignition that six of the largest fires on record in California are burning right now.

And although the Bobcat fire has not yet claimed a structure or a life, many Angelenos, faced with another day of hazardous air, are beginning to despair.

“It’s a boxed-in feeling,” said Carole J. McCoy, an artist who lives in North Hollywood. “Not being able to go outside, because I have asthma and allergies, takes away the one thing that was a sense of freedom and peace.”

McCoy was one of many L.A. residents who relied on time outdoors as a respite from stay-at-home orders issued amid the COVID-19 pandemic. But coronavirus, too, has proved no match for the fire: Smoke was so strong in parts of eastern L.A. that three coronavirus testing sites — the Pomona Fairplex, the San Gabriel Valley airport and Panorama City — will be closed Tuesday because of unhealthy air.

“You could make a list of factors here that all came together,” Patzert said of the myriad explanations for the Bobcat fire. “Some call it a perfect storm, but I call it a perfect disaster.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.