Latinos renewing bonds with religion

- Share via

Like many Mexican-Americans of her generation, Gloria Chavez found herself drifting away from Catholicism, estranged from a church that seemed cold and punitive to her. It began when she was a teenager.

“You kneeled when they (priests) told you to kneel and stood when they told you to stand,” said Chavez, now 49 and a resident of the City Terrace area of Los Angeles. “We were reared to fear the priest because we were told he was at the right hand of God.”

Though she was married in a church ceremony and her children were baptized into the church (“It was the thing to do”), she did not attend Mass regularly for years.

A visit from a nearby parish priest seven years ago, however, prompted a change in her life. From that meeting, she became involved in organizing the United Neighborhoods Organization (UNO), a grass-roots group of local church members fighting for community improvements in East Los Angeles. For Chavez, who was elected the group’s president, it was the first step back into a Catholic Church that now has meaning for her.

“Now I can integrate my spiritual needs with my community needs,” she said. “Now I can be comfortable instead of being scared.”

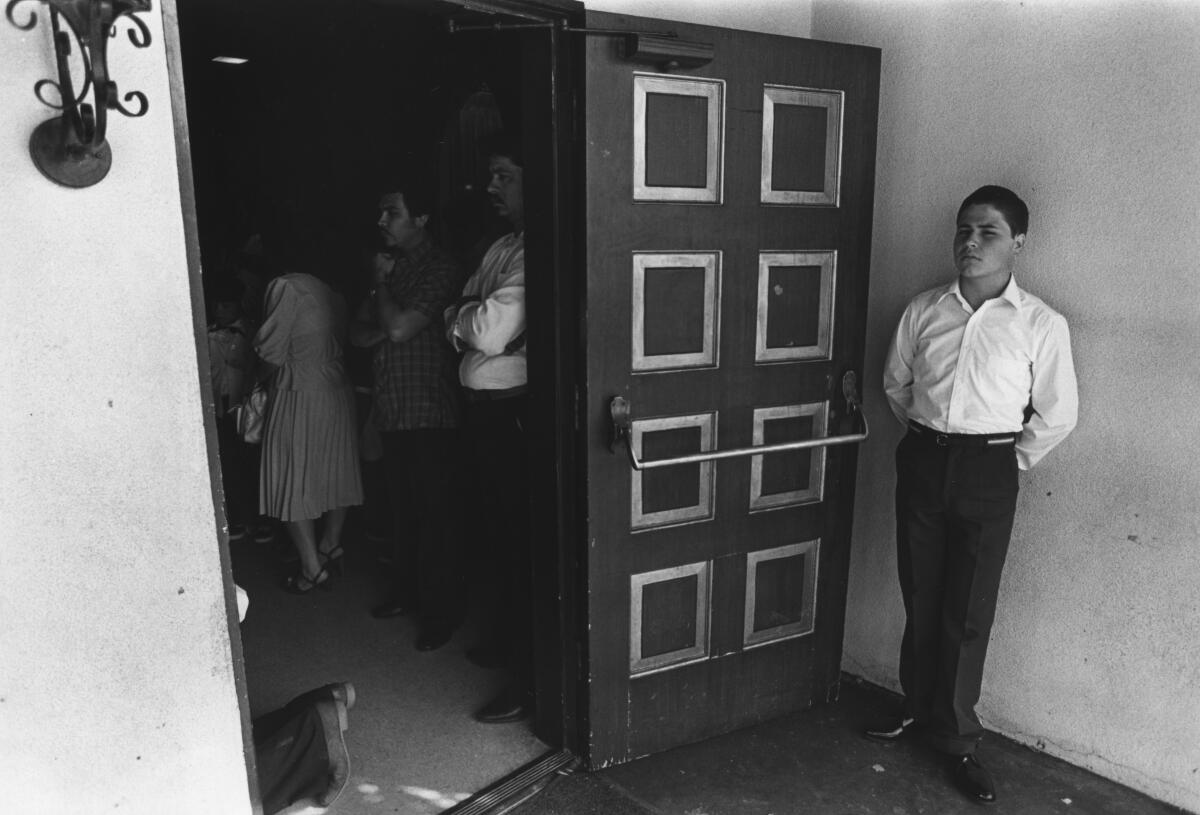

Chavez is one of a number of once-disillusioned Latino Catholics who church officials say have been steadily returning to their religion. Their return is attributed to the liberalizing changes in the church that grew out of the Second Vatican Council nearly two decades ago.

The church gradually accorded new recognition to its Latino parishioners (including Masses with a more distinctly Latino flavor) and undertook a decidedly more active role in Latino social causes.

Even during the period disaffection, of course, Catholicism remained the religion of the overwhelming majority of Latinos. It has been so for hundreds of years. The cultural and historic ties between Latinos and Catholicism date back to the Spanish explorers who brought the Catholic religion to the Americas.

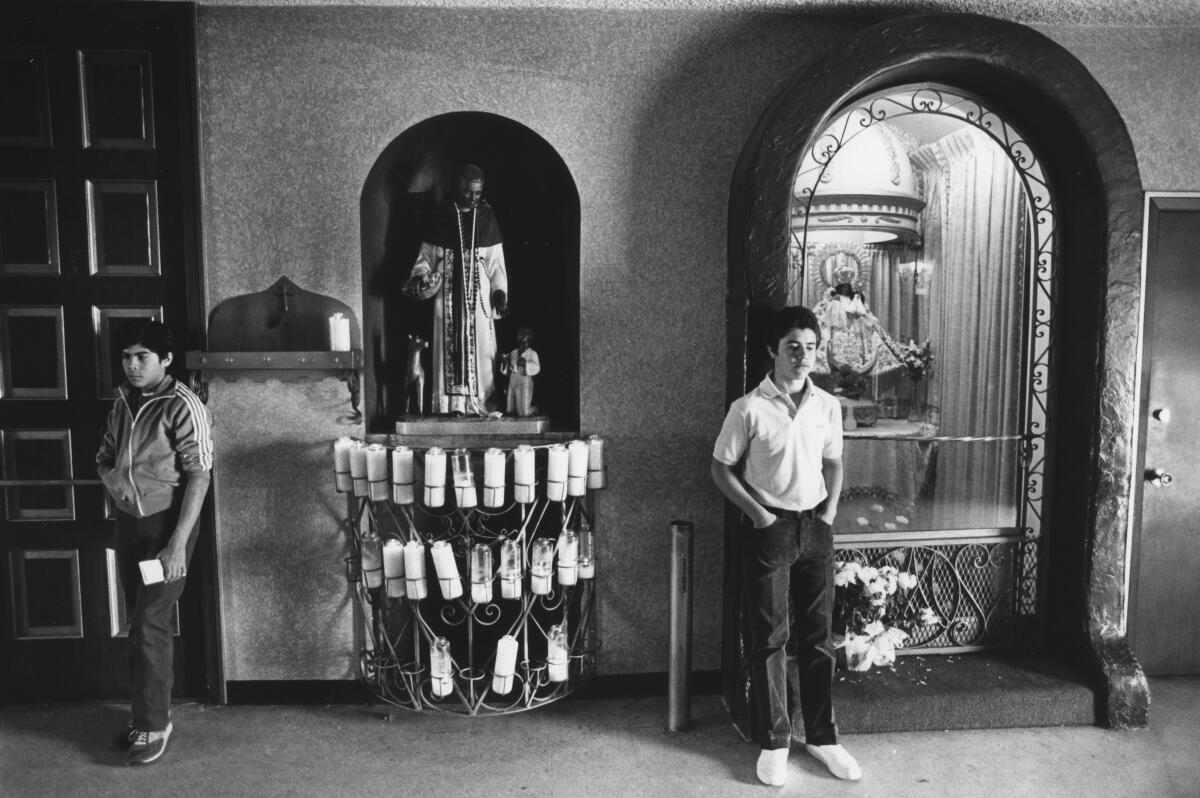

According to church tradition, the Virgin Mary appeared to a poor Mexican Indian in 1531, spurring a massive conversion to Catholicism. The Virgin Mary, whom the Indians later called Our Lady of Guadalupe, became the people’s symbol in their quest for self-dignity, freedom and identity.

“The cultural clash of 16th-Century Spain and Mexico was resolved and reconciled in the brown Lady of Guadalupe,” writes Father Virgilio Elizondo, a Catholic and Chicano history scholar, in his book “Galilean Journey: The Mexican-American Promise.” “In her, the new mestizo (racially mixed) people find its meaning, its uniqueness, its unity.”

Latinos turn to many Catholic rituals to mark key moments of their lives: baptism at birth and First Holy Communion as youths, church weddings as adults and rosarios at death.

Church officials say that nearly 90% of all Latinos identify as Catholics, nearly 13 million nationally. But as many as 80% of those, church officials say, are “lukewarm Catholics” who do not attend church or who participate in services with little commitment. No one is sure how many “lukewarm Catholics” have returned, but church officials say the movement is significant and they give the church much of the credit.

“It used to be that the priests would tell people what they could and could not do in very dogmatic fashion,” said Bishop Juan Arzube of the Los Angeles Archdiocese, which includes Los Angeles, Ventura and Santa Barbara counties. “Now we explain the teachings and let the people take the responsibility of applying them to their individual lives. As a result, people who 10 years ago stopped coming to church (are) returning with greater participation.”

Priests also say they are seeing people who once attended Sunday Mass simply out of habit participating with greater fervor. These people now “feel they are a part of the church, like it belongs to them and not just to the priests and the nuns,” said Father Francisco Mateos, pastor of Santa Isabel Catholic Church in Boyle Heights.

Celebrating Mass in Spanish instead of Latin — made possible by Vatican II — is also making a difference.

“It was not so much saying the words in Spanish,” said Archbishop Robert Sanchez of Santa Fe, N.M., “but that the spirit of the Mass took a character all of its own. There was more of a warmth and intimacy to it. . . . People began giving abrazos (embraces) at the kiss of Peace (greeting).”

Latinos also are returning to the church “because the church has become more aware of the presence of the Hispanic and is responding to that,” said Sanchez, who was appointed the nation’s first U.S.-born Latino archbishop in 1974.

At last year’s conference of U.S. bishops, for example, and ad hoc committee for Hispanic affairs began drafting a pastoral statement of interest and concern for Latinos, who are estimated to comprise about one-fourth of the nation’s 52 million Catholics.

A first draft of the pastoral statement was distributed in early July for public comment. The committee expects to seek full approval by the bishops in November.

Attempts by Latinos to turn the church toward a more vigorous involvement in modern-day social and political issues began with demonstrators in the late 1960s. on Christmas Eve, 1969, a group calling itself Catolicos Por La Raza picketed St. Basil’s Catholic Church in Los Angeles demanding that the church become more involved in Mexican-American social and economic problems..

In 1970, a group of Latino priests across the nation formed PADRES (a Spanish acronym for United Priests for Religious, Educational and Social Causes) to campaign within the church bureaucracy for increased attention to Latino issues.

The Roman Catholic Church hierarchy has responded to all this by appointing 15 Latino bishops (including two archbishops) nationally in the last 13 years, publicly supporting the efforts of farm labor leader Cesar Chavez, providing welfare relief for the poor and recent Latino refugees and helping organize such community groups as UNO.

“UNO has done a lot, not only socially and politically, but religiously,” Arzube said. “People now gather to pray together, too.”

Ironically, the movement back to an active Catholicism comes during a period of success for Protestant proselytizers intent on converting Latinos who are lapsed Catholics.

The Hispanic secretariat for the U.S. Catholic Conference in Washington, D.C., said that as the height of the exodus in the early 1970s, as many as 10% of Latino Catholics nationally and 20% in heavily Latino Southwest cities like Los Angeles converted to other religious denominations.

In a special Los Angeles Times Poll statewide of 568 Latinos, 89% said they had been reared as Catholics, 7% as Protestants.

But 9% of those reared as Catholics said they practice a different religion now (most have become Protestants) and another 8% said they no longer practice a religion.

Many Latinos who have converted say Protestant churches offer them smaller congregations, Spanish-speaking clergy who take a personal interest in their lives and an emphasis on a personal relationship with God.

“There was something missing in my life when I was Catholic,” said Raul Marquez, 46, of Lake View Terrace, who with his wife converted to Protestantism four years ago. “It seemed I was doing things more out of habit or tradition. Now I feel the freedom to worship and pray with my heart. I talk to the Lord man to man.”

An exact figure on the increase in Latino Protestants is difficult to determine. Most churches don’t tabulate statistics separately for Latinos; other denominations count only those Latinos attending Spanish-language churches and ignore the large number of Latinos who attend predominantly Anglo churches.

But evangelical denominations such as the Foursquare Gospel church and mainstream Protestant denominations such as the American Baptist and United Presbyterian Church report membership gains among Spanish-speaking converts.

One of the most successful is the Assemblies of God Church. Of its 10,173 churches, 1,043 are Latino. Of 400 new churches last year, 114 were Spanish-speaking, church officials said.

Catholic Church officials clearly would prefer that the Latino defections to Protestant denominations not occur. But Arzube minimizes their effect, saying: “If it’s a lukewarm Catholic who was not going to church anyway, fine, let him go get the Gospel there.”

At one time, Latino cultural ties to Catholicism were so intertwined that many Latino Protestants were seen as traitors to be ridiculed and taunted by Latino Catholics. Latino Pentecostals were disparagingly referred to as “Hallelujahs,” a reference to the often emotional outburst at their church services.

The Rev. David Espinoza, an Assemblies of God minister in San Fernando, recalled that as a boy in the late 1940s some of his classmates harassed him when they found out he was not Catholic.

“The biggest kick of some of the Catholic kids was to wait for me and twist my arms or hit me until I said a cuss word,” Espinoza said. “Then they would all break out into laughter and say, ‘Look at the Hallelujah, he said a bad word.’ It was like they could not tolerate the thought that a Latino could be anything but Catholic.”

That cultural bias against Latino Protestants even figured in last year’s Democratic state Senate primary in East Los Angeles.

In the closing weeks of the bitter race between incumbent state Sen. Alex Garcia and Assemblyman Art Torres, Garcia sent campaign literature to the district’s Latino voters identifying Torres as a Baptist who could not speak Spanish. Garcia characterized himself as a good Catholic whose first language is Spanish.

But Torres, who is fluent in Spanish and was baptized a Catholic but reared a Baptist, managed to overcome the implication that he was somehow less Latino because of his religious beliefs. He defeated Garcia in the primary and was elected to the Senate in the general election.

In the summer of 1983, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Latino community.

Church officials say that one reason proselytizers have been successful with inactive Latino Catholics is an acute shortage of priests, particularly U.S.-born Latino priests. The shortage has prevented the church from providing many parishioners with adequate instruction in the church’s teachings, they say.

“I know that (lapsed Catholics) do not have the basis by which to live and understand their faith,” Archbishop Patricio Flores of San Antonio said. “It was more por costumbre (out of habit). The proselytizers know that is a weakness of Catholics and they do take advantage.”

According to the Catholic Secretariat for Hispanic Affairs, 1,485 of the 58,000 priests in the country, or fewer than 3%, are Latino. Of these, only 400 are native-born.

“We just don’t have a history of it,” said Flores, who in 1970 became the country’s first Mexican-American bishop. “In the past, whenever they needed a priest, (the church hierarchy) would bring one in from Spain. They felt it was easier to import a priest rather than make one, so they did not really promote native vocations.”

The U.S. takeover in the mid-1800s of what is now the Southwest forced Mexican Catholics to become part of a predominantly Irish-American Catholic Church that was culturally unprepared to deal with Latinos. Most Mexican priests were sent back to Mexico and replaced by Irish and German clergy. According to historians, signs appeared at several Catholic Churches in the Southwest during that time, reading: “Last three rows for Mexicans.”

“By every rational standard (Latinos) should have left the church,” said Elizondo, the priest-scholar from San Antonio.

Elizondo said that many Latinos did become indignant enough to stop attending Mass, and many built altars at home where they worshipped in private with their families.

Priests say that one way to get Latinos back into the church is to improve the seminary training for priests who will be assigned to parishes in the Latino barrios.

One religious order, Divine Word Missionaries, is already doing that in Boyle Heights with its Casa Guadalupe. The “barrio seminary” was founded in 1976 to give Latinos interested in becoming priests or brothers a “realistic idea of what ministry in the Latino community has to offer as well as what difficulties there might be,” according to the seminary director, Father Gary Riebe Estrella.

The college students in the program receive traditional religious training and live in a communal setting. They also are required to minor in Spanish and Chicano or Latin American studies while in college.

“It’s a real attempt to do church in a kind of new way that has its eyes really fixed on transforming society,” Riebe said.

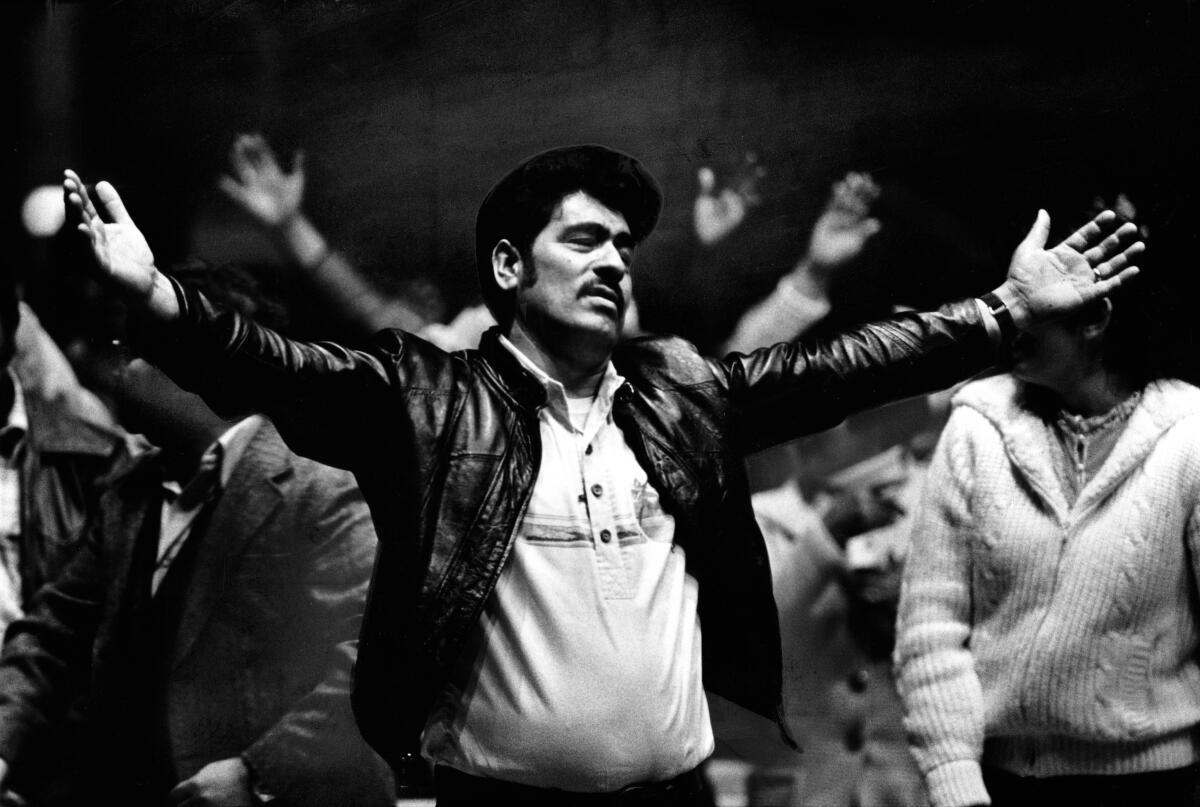

While many Latinos have returned to the Catholic Church because it is becoming more involved in community issues, others are returning because of the Catholic Charismatic movement. Its leaders seek out Latino Catholics who have abandoned the church.

Marilyn Kramer, a former Assemblies of God minister who converted to Catholicism in 1972, heads Charisma in Missions, an East Los Angeles-based organization that, like the Pentecostals, emphasizes the Scriptures and a personal devotion to the Holy Spirit.

“We evangelize to those who attend Mass but are not allowing their lives to be lived out through the Eucharist,” Kramer said. “We evangelize to those who are baptized . . . who have been confirmed . . . personal relationship with our Lord.”

Charisma in Missions holds monthly services at the Olympic Auditorium that attract between 5,000 and 7,000 Latino Catholics. They clap their hands and sway while in song, they cry while praying with uplifted hands, they shout out “hallelujahs” during the sermon and occasionally they speak in the “tongues of the Holy Spirit.” Except for the manner in which Communion is administered at the end of the service, it could easily be mistaken for a Pentecostal service.

Similar services on a smaller scale take place throughout the county. According to Kramer, there are 140 Spanish-speaking “prayer communities” of Charismatics in the Los Angeles Archdiocese.

“I used to go to church just to criticize and see what people were wearing,” said Teresa Vinson, 45, of North Hollywood, who attends Charismatic services at Santa Rosa Catholic Church in San Fernando. “I really just had the tag of being a Catholic.

“But the Charismatic movement has shown me that it was me that was cold, not the church. Antes pensaba que era un dios de castigo, pero ahora se que es un dios de amor. (I used to think He was a God of punishment, but now I know He is a God of love).”

The Charismatic movement is officially recognized by the archdiocese, but is still not accepted by all priests. However, many have embraced the spirituality and the concept of a personal relationship with God that is expounded by the Charismatics.

Bishop Arzube, for one, believes there is a growing tendency within the church to go by values rather than norms.

“We have to be open to certain values, to individual cases,” he said. “We have to be human enough to be understanding to realize that exceptions sometimes exist. Even Christ broke the Sabbath. As Christ said, the Sabbath was made for man and not man for the Sabbath.”

Even with such controversial subjects as birth control, Arzube said the final decision of right or wrong should be a personal one. “If they are truly sincere. (that issue) is eventually between God and the individual person,” he said.

This story appeared in print before the digital era and was later added to our digital archive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.