Chicano art: An emerging generation

- Share via

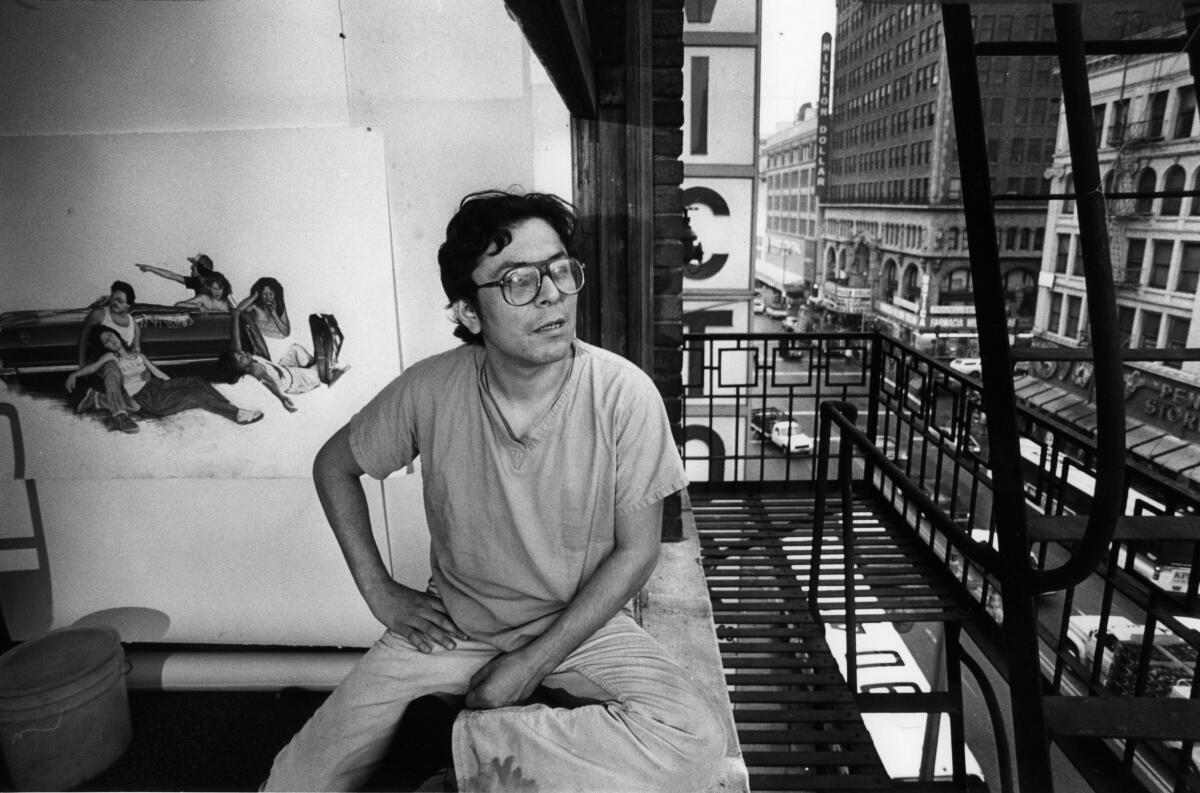

Artist John Valadez stands amid Chicano youths, middle-aged Latinas and blacks rushing to a bus stop near 4th Street and Broadway. A camera hangs from his neck; his concentration is focused on an elderly Chicana blankly staring into a storefront window bursting with gaudy radios and appliances.

Valadez, 32, raises his camera and photographs the woman’s face reflected in the storefront window. This is one way he captures the people and streets of downtown Los Angeles that fill his large canvases.

As more Chicano artists like Valadez enter American art galleries, they are attempting to make sense of the direction of Chicano art in this decade, a decade that has seen the emergence of a generation of artists like Valadez, Harry Gamboa, Carlos Almaraz and Barbara Carrasco.

At one level, their concerns and complaints are those of all other aspiring artists. But at another level, they express the belief that Chicano and Latino artists have unique contributions to offer to Los Angeles culture.

What has not often been sought by the media are their views of the social and cultural reality that they live and work in—views critical of the media themselves and of the Los Angeles art establishment.

::

Valadez began painting as the Chicano mural movement ended, an artistic as well as social and cultural movement which lasted from 1965 to 1975. Though not always a conscious process, he said he began dropping the politically and culturally inspired images of plumed serpents and Aztec pyramids for a less culturally bound language.

He said he chose social realism because it allowed him to express the values of the Chicano art movement for a larger public, while at the same time showing realistic and intimate images of Chicanos and Latinos. To Valadez, his images of Latinos are subtly subversive in the Anglo gallery setting.

In the summer of 1983, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Latino community.

Valadez said he nurtures his work with the rage and hunger for justice learned while growing up in the Estrada Courts housing project in Boyle Heights; an anger that brings him back to the image of the cholo, or pachuco (cool dude).

“I like to show the pachuco image,” he said, “even if some Chicanos who are trying to assimilate think they left this in the past. It’s still something that is very much with us. It’s 10 times worse. The drugs are worse, the violence is worse.”

But there are more important reasons why he paints the pachuco. This image displays, as Valadez puts it, a spirit of rebelliousness, “the beauty of a people we have been told are not beautiful.”

Despite his Mexican bent for vivid colors and strong emotions, Valadez has a vision of Los Angeles that makes him a very American artist. What he sees in the street goes beyond Chicanos to the transformation of American cities, due to the influx of Latino and Asian immigrants.

Other Chicanos pressured by the economic hardships of the 1980s and attracted by the boom in downtown galleries also have claimed Los Angeles.

For Margarita Nieto, a Chicana art and literary critic who has written about artists such as Valadez in Mexico and the United States, this process of redefining the city’s cultural landscape is significant: “Los Angeles is finally coming to grips with what its cultural history really is,” Nieto said, adding that there is a subtle and gradual realization here that Los Angeles does have roots, ancient roots extending to Mexico, Latin America and Asia.

But this realization is quite different from the Hispanic decade, hyped by a media that discovered the Chicano mural movement after it ended in 1975. Rather than the powerful Chicano social awakening that molded an artistic movement, there are many individuals experimenting with a series of possibilities.

This is Shifra Goldman’s view of Chicano art since the mural movement. A historian and guest lecturer on modern Latin-American and Chicano art, Goldman has been one of the most active chroniclers of the evolution of Chicano art. Today, she said, while some Chicano artists are trying to enter the gallery or continue with muralist tradition, others are strengthening their ties with Mexico and Latin America.

One such artist is Harry Gamboa. The reasons for this are obvious, said Gamboa, a conceptual artist who has exhibited his photographs in Berlin as well as the Instituto de Bellas Artes, Mexico’s national art museum.

Gamboa, who also writes for the performance group Asco (Revulsion), said the best audiences for his fiction and photography are in Mexico City and in the Spanish-speaking community of Los Angeles via La Opinion, Los Angeles’ Spanish-language daily newspaper.

He finds his acceptance ironic because he doesn’t speak Spanish. Still, he said, Mexican interest in his portrayal of alienated urban Chicanos shows an openness he has not found in the United States.

“My work is appreciated for its inherent beauty or strangeness. There’s no connection to all the negative imagery (about Chicanos) that has been injected into almost everyone in this country” by the media, he said.

This return to the source is not new. It first occurred, said Goldman, when Chicanos turned to the masters of Mexican muralism (David Alfaro Siquieros, Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco) in the 1960s. Later, she said, interest in Latin America was spurred by the Cuban poster movement, which was known for borrowing the latest trends in avant-garde painting and poster making to convey social and political messages.

Now, some Chicano artists seek to regain the cultural and political momentum of the mural movement by looking to Mexico and revolutionary Nicaragua for inspiration. But this cultural dialogue also is taking place in the United States.

Locally, a strong voice in stimulating it is Sergio Munoz, editor of the community section of La Opinion.

Munoz “was the first one who had the vision to put Chicanos side by side with contemporary Mexican and Latin-American artists and writers,” Goldman said.

Regretfully, said Gamboa, Munoz’s openness is rare in local media.

More common, he said, is the reaction of an editor of a local avant-garde magazine, who understood his photos and article on Chicano lowriders “as something people can just watch, a sort of cultural voyeurism.” Just as typical he said, are museum curators who have gathered Chicano works in huge, undefined shows to relieve their limited sense of social responsibility.

There are many artistic accomplishments by Chicanos locally, Gamboa conceded: the “Los Four” exhibit at the County Museum of Art in 1974, Asco’s own exhibit at the museum a year later, the Craft and Folk Art Museum’s “Murals of Aztlan” show in 1981 and the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery’s regular exhibition at Barnsdall Park of Chicano artists.

But except for open doors at Barnsdall, Gamboa said the other achievements weren’t more than token gestures.

While the motivations Chicano artists like Gamboa ascribe to this city’s art Establishment may be distorted, they nonetheless underline a basic flaw they see in Los Angeles.

“It still remains that Los Angeles is a (culturally) segregated city,” said Nieto. “Consequently, Los Angeles has no focal point. The mainstream doesn’t look at Latino art and Latinos don’t look at mainstream art.”

However, Chicano artists have to share the blame for their isolation.

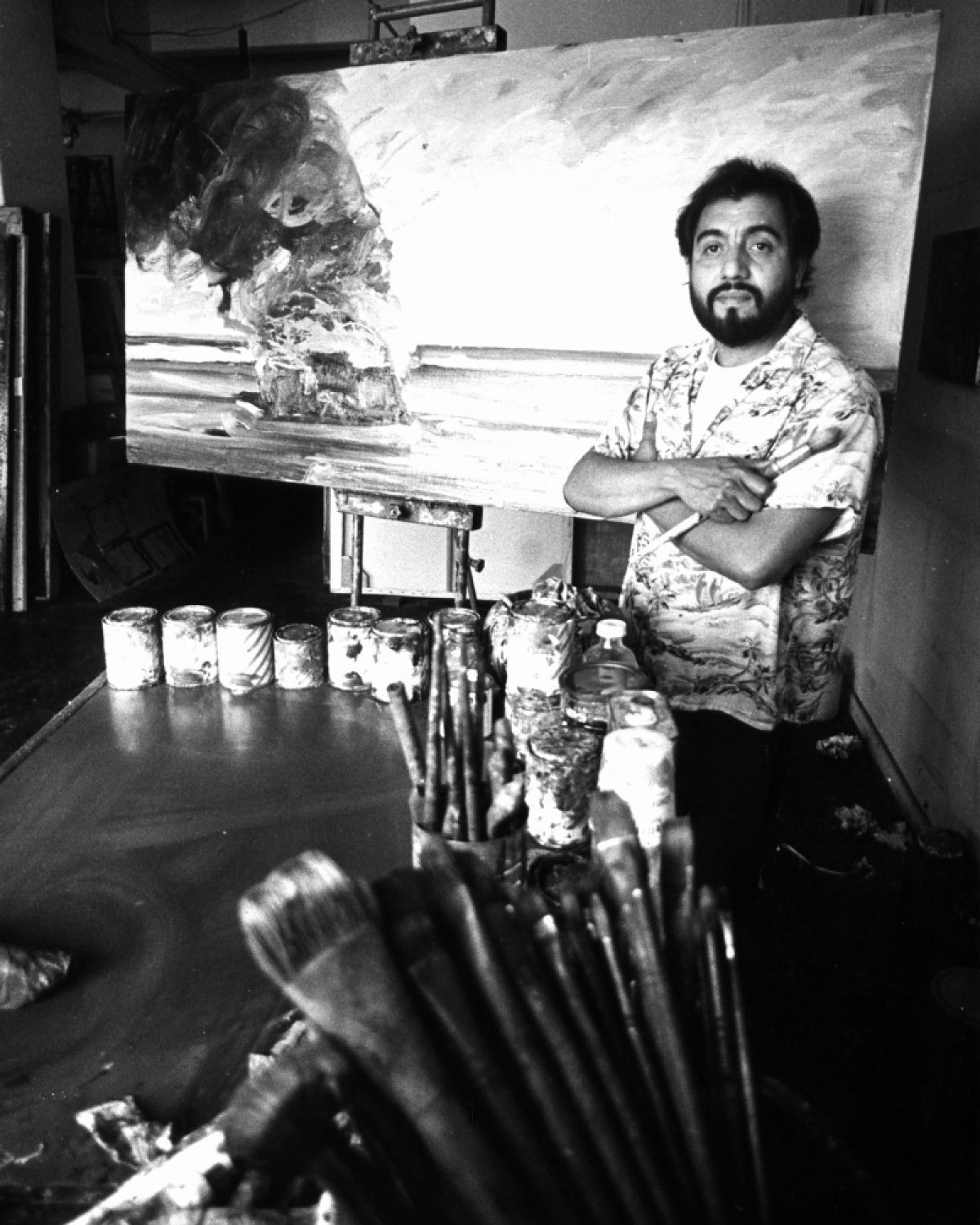

Carlos Almaraz, known nationally for his dream-like pastels of Echo Park, his fanciful ineluctably Mexican bestiary and expressionistic freeway car crashes, said that a refusal to cut the umbilical cord to the barrio typifies the thinking that traps most of his peers.

“The Chicano artists I speak to are still waiting for someone to care for them,” said the 40-year-old artist, adding that this attitude was so strong that it prevented any progress when he was a member of several Chicano arts collectives.

He said Chicano artists can only grow by learning to survive in the marketplace rather than by depending on grants or the shelter of nonprofit organizations. The artists that depend on such organizations, he said, avoid facing the fact that their work is often mediocre.

“I think it’s too easy to say it’s racism or classism,” he said. “I’ve seen hundreds of portfolios, and the kids have a lot to learn. I have rarely found that anyone who is truly terrific is being ignored,” adding that the arts naturally tend to include outsiders in the dialogue.

Almaraz, who identifies himself with the new-imagist movement, was commissioned last year to create a poster for the Olympic Games. His large pastel of electrifying pinks and silvers that he intended would stand out against the puritanical coloration of many American artists, was the first among the 16 posters to sell out and be reprinted.

He said his next goal is to have a show in Paris. “You’ve got to get out of East L.A. You cannot make a statement about the world if you have not seen the world.”

But if Chicano artists have to stop fooling themselves about what it takes to make it, many claim that local art institutions have to exhibit art that can reflect and enrich a Chicano self-image.

Some Chicanos argue that greater access to the works of masters like Goya and Tamayo can reduce this isolation by helping young Chicano artists understand the origins and meaning of their work within traditions of lasting quality.

However, Earl (Rusty) Powell, director of the County Museum of Art, said the museum has not done enough to exhibit Mexican, Latin-American and Spanish art, let alone contemporary Chicano, black and women’s art.

But Powell said the museum’s exhibit of Costa Rican pre-Columbian art and the recent dedication of the Pauley wing of the Ahmanson Museum to the Constance McCormick Fearing Collection of Mexican pre-Columbian art represent the museum’s future direction.

While space for contemporary works will remain limited until the museum completes its new modern art gallery, he said it will continue to strengthen its collection of traditional Spanish, Mexican and Latin-American art. He added that the growth of downtown galleries should provide more opportunities for local artists, including Chicanos.

But in a city with a growing Mexican population, Nieto interprets Powell’s answers as subtle forms of evasion: “It’s very well to know Spanish and Latin-American culture, but the fact is our greatest need is to know Mexican and Chicano art. In Los Angeles, there is still a pathetic ignorance of Mexican and Chicano culture. This is the one city where this should not be. After all, Los Angeles was founded by Mexicans.”

Other Chicano artists, such as muralist Barbara Carrasco, say the cultural ignorance Nieto riles against is not restricted to the gallery or the museum.

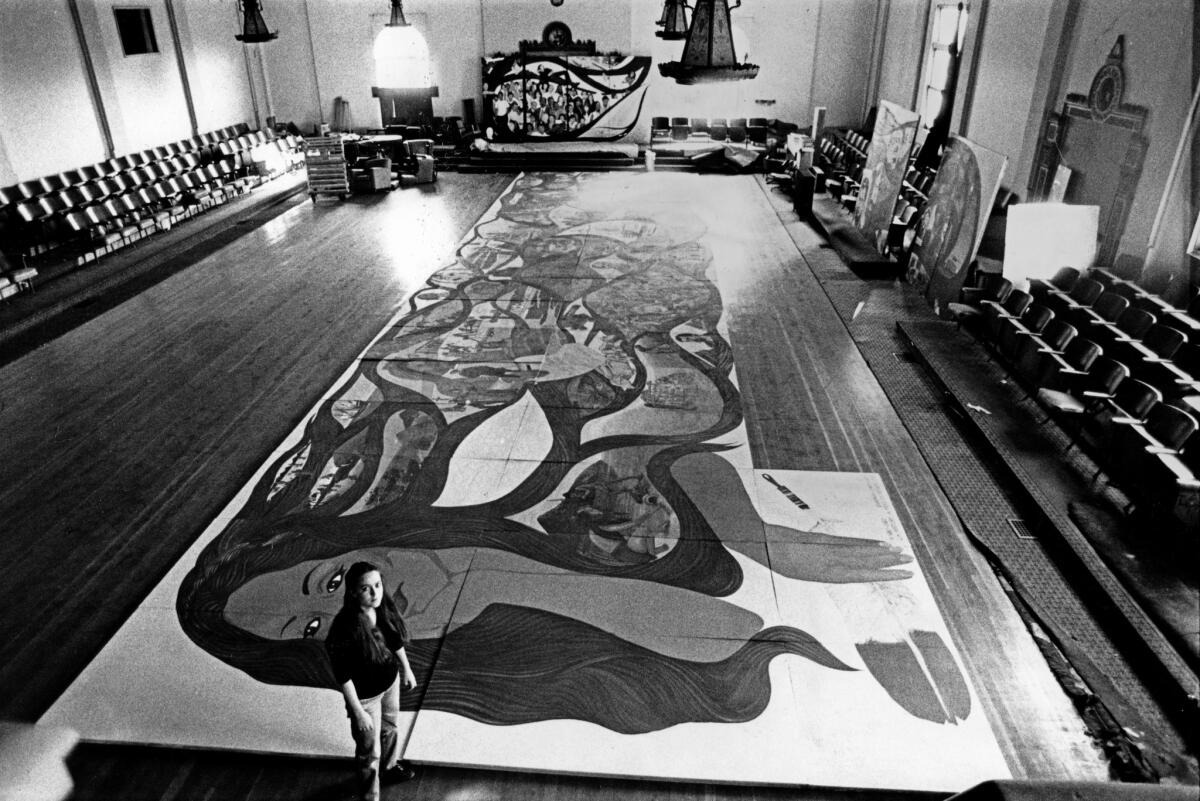

Carrasco, 27, although slight is known for her stormy temper and iron will. It’s a reputation she said she earned in her two-year battler with the Community Redevelopment Agency because she refused to be treated as a second-class citizen. She said she fought the agency’s alleged attempt to censor a portable 16-by-80-foot mural that she wanted to display during the 1984 Summer Olympics.

The mural, “L.A. History — A Mexican Perspective,” depicts scenes of minority and Chicano triumphs and oppression interwoven in the braids of a woman’s hair. Among the scenes are the arrival of the coastal Indians and later the Mexican settlers in Los Angeles, the death of Times columnist Ruben Salazar in 1970 and the success of Dodger pitcher Fernando Valenzuela.

Her problems began, she said, when the agency tried to delete scenes that it thought might be embarrassing if the mural was displayed during the Olympics. She said that Gary Williamson, the agency architect initially in charge of the project, told her that scenes depicting the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II and the mass lynching of 21 Chinese workers in the late 1800s would offend Asian visitors.

But Carrasco said she received supportive letters from Japanese- and Chinese-American community groups, stating that they would be offended if the scenes were struck.

Williamson said he requested that these scenes be omitted because they filled the mural with too many images.

Agency attorney Glenn Wasserman said the situation was compounded by a personality clash between Carrasco and Williamson and the absence of written agreement to detail ownership and display of the mural.

Carrasco said she was offered an agreement that stated the agency’s exclusive right to mural copyrights and indefinite postponement of installation.

Williamson was later removed from the project, but she said that this didn’t stop the agency from treating her poorly. Eventually, Carrasco rescued her mural from a downtown warehouse and was granted legal ownership by the redevelopment agency.

Now she’s looking for a place to display the mural. The experience has led her to draw a parallel with a similar situation involving David Alfaro Siqueiros’ “Tropical America” in 1932. Painted high up on an Olvera Street wall, it was whitewashed as soon as it was completed. The image of an American eagle preying upon a crucified Mexican peasant proved too strong for shop owners and city officials, who demanded that it be covered up.

Ignored for almost 50 years, there are attempts under way to save the mural. But rain and smog may have eroded its pigments beyond restoration.

Edmundo Rodriguez, executive director of Plaza de la Raza Cultural Center in Lincoln Park, said he understands Carrasco’s frustrations, adding that all artists have problems with government bureaucracies.

Still, he said, Carrasco’s battle with the Community Redevelopment Agency is more reflective of a basic change of attitude among Chicano artists.

To Joe Rodriguez, of the National Endowment for the Arts’ office of minority affairs, the damage appears in a declining Chicano presence withing the endowment. Rodriguez said that for young Chicano artists who need the endowment’s valuable stamp of approval, the loss of Chicano staff and panelists in the agency may be fatal.

At best, he said, the low priority the Reagan Administration has assigned to Chicanos will freeze the modest gains made under the Carter Administration. At worst, he said, the trend of replacing Chicanos in appointed positions with Anglos will return Chicano artists to their virtual invisibility in Washington before 1977.

California Gov. George Deukmejian’s funding cuts and program cancellations in this year’s California Arts Council budget will hurt Chicano artists, said Manazar, head of the Los Angeles-based Concilio de Arte Popular (the Popular Arts Council), a statewide consortium of Chicano art groups.

Still, Manazar said Chicano and Third World artists must fight the alienating forces that regulate most artists to the margins of society and tempt successful Chicano artists to dilute the qualities that have made their work unique.

For Valadez, this temptation is real enough. This is why he cultivates a rage focused on the racial and class inequities that still mar U.S. society.

“I am always going to have this resentment,” he said. “That’s what motivates me. As long as we don’t have a Utopia, I have very rich resources for my work. And if my work tends to be hostile, I am not going to change it to make a little more coin. If it’s going to be hard for me to make it, that’s how it has to be.”

This story appeared in print before the digital era and was later added to our digital archive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.