Migrant pickers: Latinos in the fields of hardship

- Share via

Each summer, we climbed into our 1957 Ford pickup and left our small Arizona town behind in the desert heat. In those days, we didn’t know we were called “migrants” or campesinos. All we knew was that we were going to la pisca (the harvest).

Our parents, Jose and Guadalupe, rode in front. The rest of us — three girls and six boys — went in back, under a canvas-covered shell that our father had made.

A can of water saved us from thirst. But fumes from the muffler gave us headaches as we drove from Eloy to California, one family among hundreds of farmworkers on the road.

We knew we were on our way to long, tough days in the fields. Even so, we looked forward to these trips because we would get to see the ocean and cities like San Francisco.

We started picking during the 1960s, when Carolina, the oldest of the children, was 14. I was 11 and still in braids. The boys were all younger.

We worked in towns that we still remember by the fruit or vegetables we picked there: onions in Wasco, apricots, bell peppers and garlic in Gilroy and Hollister, tomatoes in King City, plums in Corning, apples in Watsonville, strawberries in Salinas, green beans, grapes and more plums in Healdsburg.

During that time, Edward R. Murrow’s television documentary “Harvest of Shame” revealed the cruel exploitation of workers like us. We didn’t get to see the film. We were busy picking.

We did that work for nearly a decade simply because there were so many of us and we were poor.

Our parents never forced us to work and they never pushed us to pick faster. They taught us more by example than words, letting us conclude that the entire family would be better off if we worked together.

If we didn’t feel like working, we were told to sit in the truck. Our conscience took care of the rest. (We also knew that at the end of the season there would be some money for new clothes and school books.)

The memories have never left us.

I returned to the country recently to see if conditions for farmworkers today are any different than they were for us. The same roads led me back to the fields and into the past.

::

When I saw the workers in the fields and the labor camps, they often reminded me of my family and our experiences. Some changes were clearly evident; in other ways, it was as if time had stood still.

Some of the more visible improvements for farmworkers are migrant education programs and legal and rural health services that we didn’t have access to 15 years ago.

The short-handled hoe is now prohibited. The Agricultural Labor Relations Board, established during the administration of Gov. Edmund G. Brown Jr., settles disputes between growers and farmworkers (though funding cuts by Gov. George Deukmejian could cripple the agency).

California farmworkers now have the right to organize and engage in collective bargaining. The once-fledgling United Farm Workers established itself with grape, wine and lettuce boycotts that won national support, and has since survived both external and internal conflicts.

Union members have health insurance, pensions, medical care and access to labor and language training centers. They are paid by the hour, instead of the piece rate that forced workers to push themselves virtually beyond human limits.

But farmworkers still do not enjoy a life free of the old injustices and suffering. Their wages remain low, housing scarce, unemployment high and the risk of pesticide poisoning greater each year.

Farmworkers still die young, their life expectancy of 49 years being far short of the national average of 70.

In a recent interview, UFW leader Cesar Chavez looked back at the last two decades. “There is change,” he said, nodding his head in a reflective mood. “There is concientizacion (conscience-raising).”

But, Chavez said, “we can’t depend on the law. Laws don’t build unions. They just set rules. The growers, the employers, are very adept on how to screw you with the law.”

There are an estimated 250,000 farmworkers in California. The UFW’s membership totals 105,000, and its contracts cover 30,000 to 35,000 workers at any given time, according to Esther Winterwood of the UFW. “For those who are not in the union, have not had an election or been exposed to the union, the fear is as bad as it used to be 20 years ago,” Chavez said. “There are more workers than jobs and there is still the exploitation of that fear ... by the employers.”

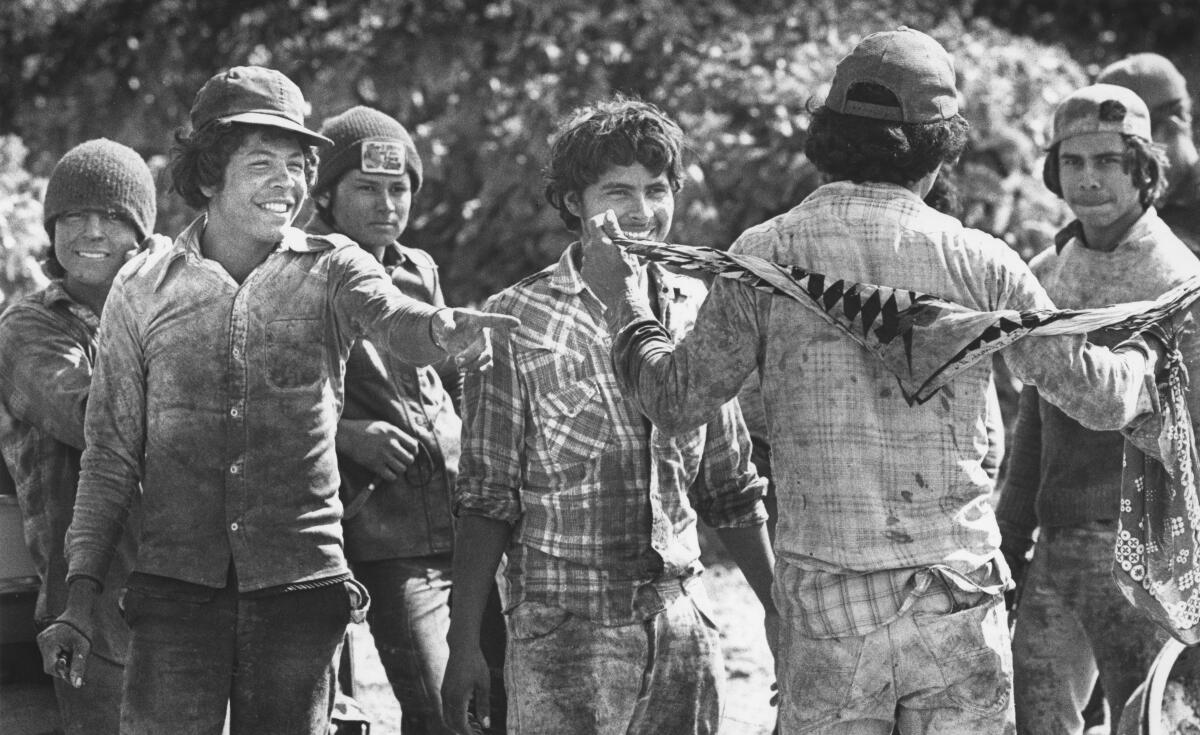

As in the past, most of today’s farmworkers are Latinos — more than 60%, according to a 1981 California Labor Market Issues report. But today, most of the people working in the fields seem to be young immigrants from Mexico, rather than Mexican-Americans.

Maria Aurora and Jose Cruz, however, are part of the old tradition, moving from state to state, harvest to harvest. They met in third grade, became sweethearts at 13, married at 15 and now have three daughters.

“Things have changed a little bit” over the years, Maria Aurora Cruz said in her kitchen at a Hollister labor camp. The boxlike dwelling where she lives has indoor plumbing, a stove and refrigerator. (Years ago, when my family stayed at the same camp, we lived in a tent and my mother cooked over an open fire.)

Remembering the harsh conditions in places like Idaho where she and her husband thinned beets, Maria Aurora, 26, said, “The foremen don’t drive us as hard as they used to and some of the camps have gotten better. One thing doesn’t change — it’s still pretty hard work.”

::

We remember. We were stooping, kneeling or standing all day, dragging or lifting heavy sacks, large buckets or crates in vineyards, orchards and fields. Since we were paid at the piece rate, we picked as fast as we could.

When we picked onions and garlic under the glaring sun, we had to endure the smell that turned our stomachs. Picking grapes meant we had to be careful with the sharp, curved knife. Grape juice and dust made the cuts sting.

If we were up in the apricot trees, there was the danger of falling off the ladder or dropping a full bucket on someone. At the end of the day, everything hurt, from our necks to our fingers, legs and backs. When we got home, our eyes felt like they had been stretched into slits and our hands and clothes were stained purple, green or brown. We were so tired we could barely eat.

When we went to bed, some of us had nightmares: thousands of berries, grapes or string beans hung before our eyes, waiting to be picked.

We tried different ways to escape the monotony of picking the same fruit or vegetable hour after hour. Someone usually had a radio and we listened to music as we worked. Most of the time, we daydreamed. Carolina, for instance, fantasized about burning the orchards down.

At midmorning and in the afternoon, our father would call for a break and a snack. We took a half hour for lunch, eaten at the edge of a field or under a tree in an orchard.

Some of our longest days were in the plum orchards, on our hands and knees picking the fruit out of the dirt clods. (The plums became prunes later, when they went into a giant dryer on the farm.) Our father always worked harder than we did. Besides picking and stacking the wooden boxes, he also had to shake plums off each tree with a long, hooked pole.

The trick to picking plums was to sweep your hands over the fruit, scooping as many as you could in one rolling motion. We were paid 25 cents a box, meaning eight of us could make about $25 if we filled 100 boxes, working at least 10 hours a day.

(The median annual income for California farmworkers in those days was $753, according to farm labor expert Ernesto Galarza. There was no minimum wage — farmworkers were not brought under the minimum wage law until 1966 — and no overtime. Last year, when California agriculture grossed $13.9 billion in national sales, the median income for farmworkers was $4,000, according to Charles Horowitz of the Migrant Legal Action Program in Washington. Nationally, farmworkers still are excluded from regulations requiring overtime pay.)

By sunset, our hair and clothes were full of dust, our hands and knees sore and bodies drained. At night when we were asleep, we sometimes moaned like wounded soldiers in a hospital, my grandfather once told me.

The next day we did it all over again, getting out of our warm beds at 3 a.m. when it was still dark and we were still tired.

As I went from field to field this year, several people told me what I had already heard from one worker:” I bet you wouldn’t want to work here now.” The answer is no.

Once you do it, you never forget. Some people cry when they go by a field, others curse it, few romanticize it.

We filled thousands of containers with the food we picked, and, like farmworkers today, wondered where it all went. In stores, we checked the labels on bags to see if they carried the names of towns where we had picked. We wanted to see the results of our work.

Most shoppers who see the attractive produce displayed at markets today don’t realize what farmworkers went through, picking the food for them.

Campesinos know how to handle each fruit and vegetable expertly. Lechugeros (lettuce workers) are considered masters at it. They move across the uneven earth with grace and speed.

Lettuce cutting is “an art,” said Javier Tijero, 27, during lunch in a plowed field. “You have to know which ones to cut, how to leave the yellow ones behind, decide which are too small, too large or just rotten, and after you do that, you should be able to cut the lettuce with only one swift stroke.”

But, he added, “Every day we leave a piece of our lungs on that earth.”

::

We carried a tent in the pickup as we made our way north each season. Finding a place to stay was always a serious problem. We lived in several labor camps, where the dwellings ranged from abandoned barracks to trailer houses.

When we first went to Hollister, we pitched our tent in an apricot orchard. Then, we moved the tent to the top of a hill where there were bathrooms. The state eventually set up prefabricated Quonset huts that appeared to be made of Styrofoam and had pleated walls.

One afternoon, the small electric stove in the hut short-circuited.

Thinking that the whole place was going to catch fire, I grabbed my mother and pulled her out. Cruz, our red-haired aunt, didn’t grab anybody. She just ran out the other door.

We laugh about that day now, but cry about the time the stove blew up in our mother’s face.

We were living in a camp of green barracks next to an artichoke field in Watsonville then. The bathrooms were in one building and the kitchen with its long tables and big commercial stove was in another.

Our mother had risen at 3 a.m. to fix our food. When she tried to light the stove, a ball of fire erupted, burning her and another woman standing at a sink nearby. Our mother returned to our living quarters, her brown eyes intense with fear, her eyebrows and eyelashes gone.

All she could say was, “Mira, me queme la cara con la estufa (Look, I burned my face with the stove).”

When you’re a child and see our mother hurt like that, the horror stays locked up inside.

Last year, another communal stove exploded at another camp in Watsonville.

This time, the fire ignited a pregnant woman, killing her, her unborn child and an 8-month-old baby. The woman’s sister was badly burned when she tried to rescue the baby. A subsequent county investigation found more than 50 gas leaks in the camp, according to Lydia Gonzalez, an attorney for the California Rural Legal Assistance.

Jim Hicks, a Watsonville real estate man and owner of the camp, said the woman’s relatives were awarded $130,000 by his insurance company. “And they didn’t deserve any of it (the money),” he said. “It was an accident. She burned herself up.… There was no faulty gas leak whatsoever.”

My travels this year showed me that the housing shortage for farmworkers is still critical. Some have been forced to live in trees, converted boxcars and chicken coops, in places that are no more than hovels. Fewer than half of the labor camps in the nation have indoor plumbing, according to the Migrant Legal Action Program.

There are 25 state-operated labor camps, but they open their doors for only six months each year and shelter only 2,000 of the estimated 250,000 farmworkers, according to Fortino (Mike) Cardenas, a former farmworker who has directed state migrant services for the last seven years.

The state has built some new housing but the shortage is so severe that farmworkers line up in front of labor camps for days before they open.

No relief is in sight. State prospects for new housing are limited and federal assistance from the Farmers Home Administration has been cut nationwide by 85%, or from 2,575 units in 1979 to 388 units in 1984, according to staff aides to state Sen. Nicholas C. Petris (D-Oakland).

::

People used to tell us that machines would eventually do the picking and that there would be no more jobs for farmworkers. Mechanization affected our family early. Our father was a foreman in the cotton fields in Arizona until the picking machines took over, leaving him without a steady job.

We still could not envision machines picking grapes, tomatoes and bell peppers, which we thought were all too delicate for metal devices. But now, the predictions seem to be coming true.

In the onion harvest, for example, metal pickers with about 10 workers now sweep up the onions and drop them into sacks.

When we picked onions, there were as many as 100 people in some crews. We used big shears with sharp blades to trim off the “beard” on the bottom and the top, dropping the onions into a bucket underneath. Then we emptied the buckets into burlap sacks.

Farmworkers are not against inventions that make life easier or more comfortable, but they object to the unemployment that mechanization brings. It intensifies their poverty, leaving them — especially the older ones — with no hope and no future.

The UFW in its contracts and the California Rural Legal Assistance agency in a lawsuit are both pushing for retraining of displaced farmworkers.

When the tomato harvester was invented and a tomato better able to withstand mechanical picking was developed, the result was displacement of 55,000 workers, said William Hoerger, an attorney for CRLA.

The CRLA has sued the University of California, complaining that it used money and agricultural divisions to conduct mechanization research instead of developing programs to help small farmers, farmworkers and consumers.

The suit also argues that the university system has benefited a few large-scale corporations as well as university regents who have financial interests in research projects they have approved.

For farmworkers like Concepcion Gutierrez, “La Electronica” is as ominous as it sounds. Gutierrez, her two children, her sister and 74-year-old mother drive hundreds of miles from Texas to California alone. When Gutierrez was pregnant, the mother took her place in the Gilroy garlic fields.

“They tell us we won’t be needed 20 years from now,” Gutierrez, 38, said as she rolled out tortillas one afternoon. “Well, the future is already here.”

But H. Edwin Angstadt, a grower-shipper representative, points out that “so far, nothing has been devised that can replace the decisions the human being has to make when they’re harvesting fresh produce.”

In fact, because of agribusiness lobbying, a three-year extension on the use of undocumented farm workers is included in immigration legislation now before Congress.

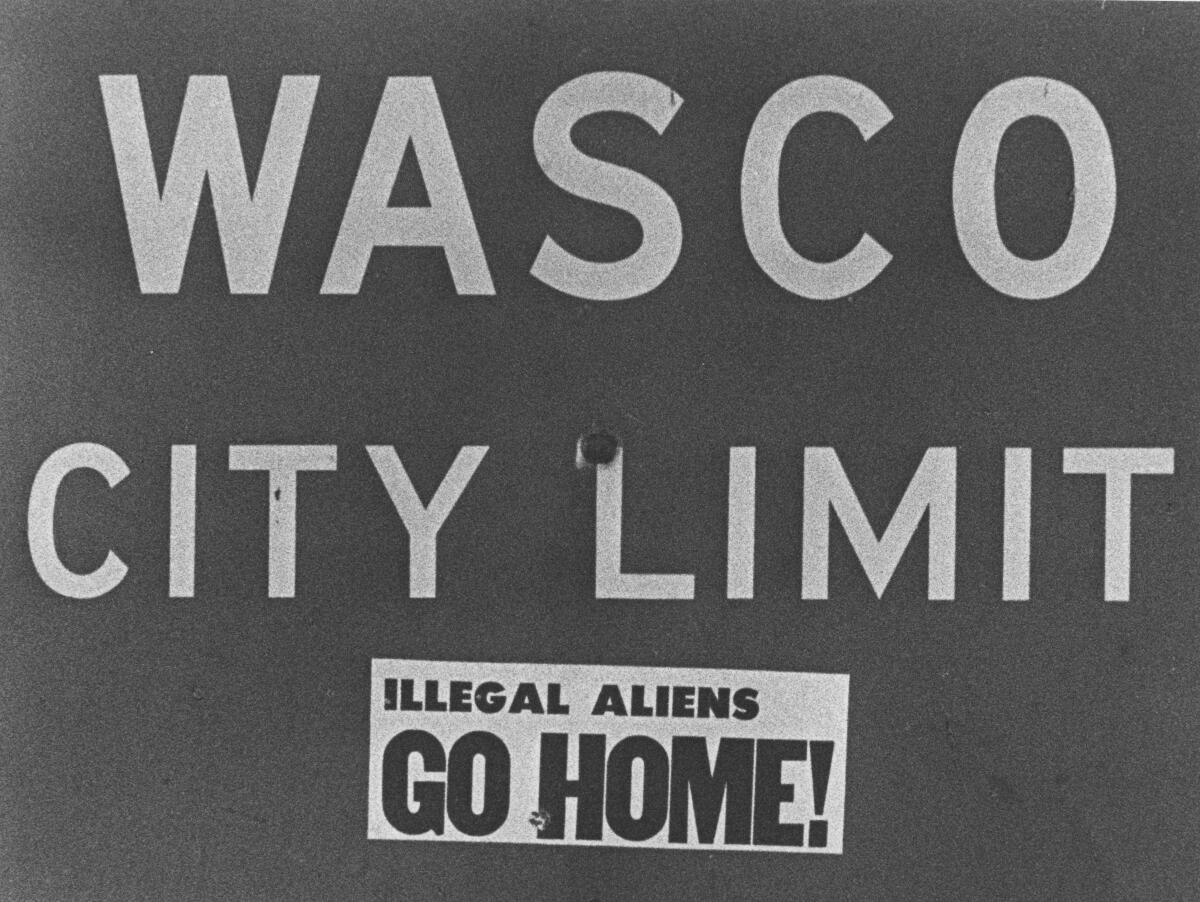

Immigrant farmworkers, meanwhile, worry that they will not qualify for amnesty under provisions of the immigration bills, and mass deportations will result. Their fears are reinforced by such messages as this one bumper sticker in Wasco: “Illegal aliens go home!”

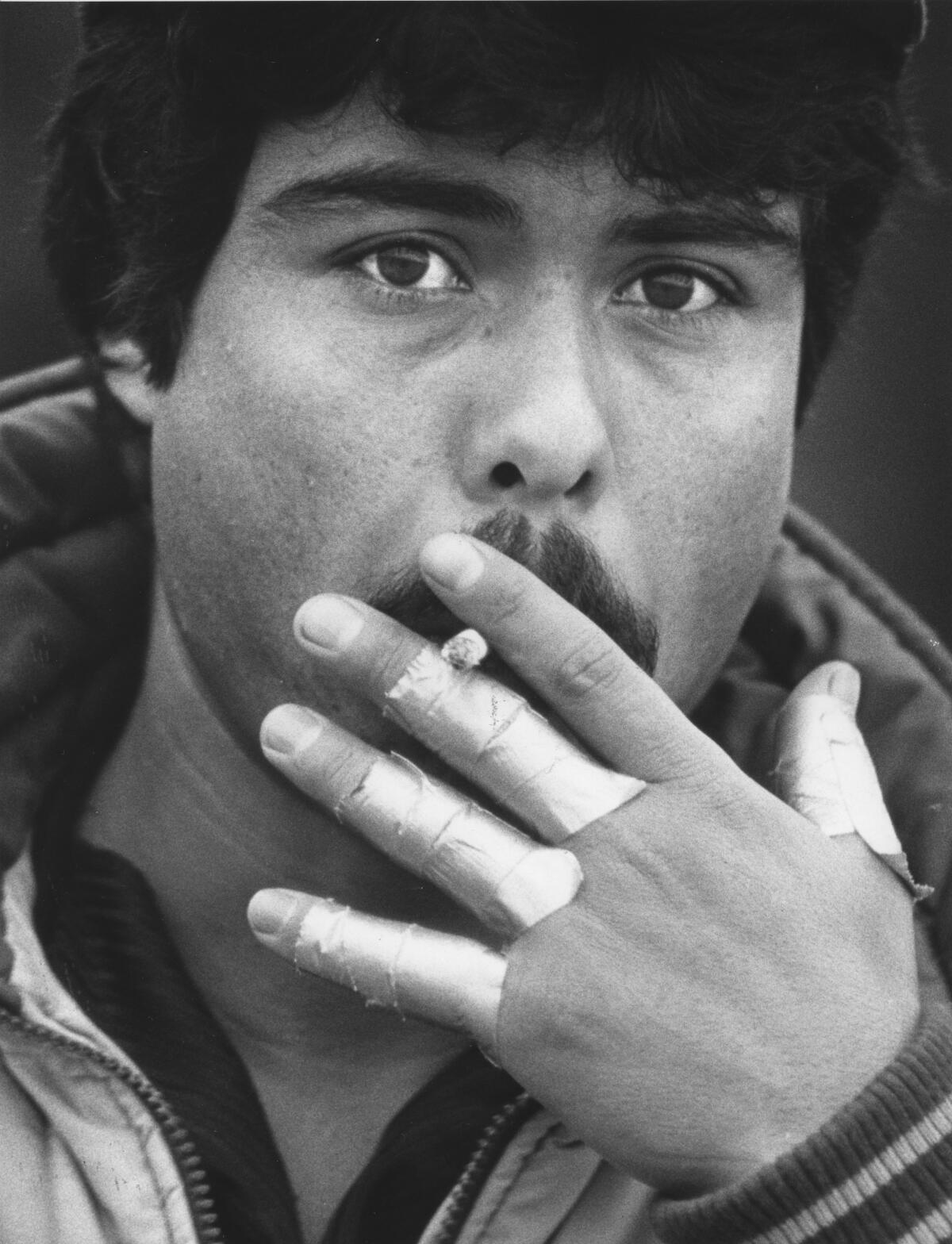

Gustavo Gutierrez, a 19-year-old from Mexico, said, “People have never placed much importance on our work. But what would happen if all the farmworkers left the fields? We provide what every human being needs for survival — food.”

::

Farmworkers have one of the highest rates of fatalities and injuries on the job, exceeded only by mining and construction workers. Farmworkers develop circulatory and respiratory problems from stoop labor and hazardous working conditions, such as exposure to pesticides.

In Monterey County, where more than 8 million pounds of pesticides were sprayed on fields last year, four mass poisonings of farmworkers have occurred within the last three years. In those incidents, farmworkers went into recently sprayed fields, illustrating the flaws in an ordinance that requires posted warnings of unsafe areas but does not require listing the spraying date or chemical used.

Rafael Hernandez and Adrian Luna have been poisoned twice, and fear that they have suffered permanent damage. Hernandez suffers from blurred vision when he tries to read and Luna has nausea and headaches almost every day.

Despite the growing problem, some doctors are failing to diagnose or treat pesticide poisonings properly, mistaking some symptoms for the flu, according to Dr. Antonio Velasco, a physician who has treated hundreds of pesticide poisoning cases in the Salinas Valley. Others are failing to report suspected or confirmed poisoning cases as required by law, he said.

Years ago, my family was picking tomatoes in fields that had been irrigated during the night. The humidity the following morning made Carolina break out in red, swollen splotches.

Our other sister, Rosela, woke up one night, vomiting from the powder sprayed on apricots.

Once, I awakened in the middle of the night, one of my eyes on fire and throbbing in pain. After searching for two days, my mother found an ophthalmologist. But he couldn’t tell us what caused the injury. I believe it was a pesticide or a particle from tomato plants that somehow worked its way into my eye. It left a scar that still burns.

Today, there are 60 rural health clinics in California, compared with 17 two decades ago. They make healthcare more accessible to farmworkers who continue to suffer from back disabilities, high blood pressure, stress and the effects of poor diet, according to Luisa Hernandez, executive director of La Clinica Popular del Valle de Salinas.

She said that many women, in particular, visit the clinics “very depressed with complaints about aches and pains that are often not related to any organic disease, but to stress.”

These women, from Mexico, have “grown up in small towns and know everybody in the town, are close to them and usually share child care,” she said. Now they live an isolated life “burdened with all the responsibilities at home (and) having to go to work as well,” she added.

::

We helped our mother with the chores, but she was usually the first one up and the last to go to sleep. She did housework, and went into the fields with us.

“Mom was tired,” Rosela remembered. “I don’t think she even wanted to go. She got up to go help dad with us. I always felt that she thought she owed him that, because she didn’t work the rest of the year. I didn’t think it was fair for her to go.”

A small woman with short, black hair and round cheeks, our mom was “muy blandita,” as our father said. “Very soft.” Three years after the family stopped picking, she died of cancer. She was 45.

Other women we knew went to the fields even when they were pregnant. Today campesinas like Jessie Flores and Josefina Gutierrez of Salinas still work through the third month of pregnancy. They return to the fields 40 days after their children are born.

“The company would fire us if we took any longer,” Flores said.

The women come from migrant farmworker families in Mexico, and have been in the fields for at least 16 years.

“Our parents put us to work because we needed the money,” Gutierrez, 32, said. “You know how it is, we couldn’t do anything else except what they told us to do until we got married.”

Like most farmworkers, they don’t want the same life for their children and are sending them to school.

Some children, like Jose Villa, still accompany their parents to the fields, either because the family cannot get by without their help or because there is no child care available.

Villa, a 4-year-old with black hair and brown eyes, was bored in the Gilroy walnut orchard where his parents were picking.

“I work,” he said, trying to explain the situation. “But I don’t work.” Then, he jumped onto his father’s back.

There are about 700,000 children registered in migrant education programs across the nation. Horowitz of the Migrant legal Action Program said. “No telling how many more aren’t,” he added.

::

We were luckier than other farmworker children. Our parents took us out on weekends. We would go to Santa Cruz where we rode the roller coaster or to Monterey where we had picnics on the beach. Sometimes the boys went fishing with our father.

As we climbed out of the truck in our Sunday best, Anglos would ask our parents, “are all of these children yours?” Our parents knew we were theirs all right, but sometimes our father would start counting real fast to make sure none of us had become lost on the way back to the truck.

At the end of the season, we usually made it home in time for school. Our parents thought that was important.

Our father often told us how hard life was without an education. (He was the son of farmworkers from Mexico and has worked in the fields from Texas to Montana since he was 7. He would have liked to have been a lawyer and still speaks up for people who need help, using what Carolina calls his “silver tongue.”)

Our mother, a self-educated intellectual from New Mexico, made sure we learned to read and write.

If we didn’t make it back by September, we started school in a new place. In some areas, there were few brown faces like ours.

When I was in seventh grade, a teacher named Mr. Pearce decided I was invisible. He never called on me, no matter how often I raised my hand to answer questions. He didn’t call my name when he took roll either, even when I sat in front.

The day I told him I was checking out, he didn’t say anything. He just looked over my head until i walked out of the classroom.

::

At the end of a picking season, farmworkers who have their own housing in communities like Salinas remain there. Those living in labor camps try to find other housing and other jobs when the camps close down. The rest pack up and go back home, without jobs for the time being.

It was no different when my family was on the road. At the end of the harvest, we collected our paychecks and loaded up our possessions.

With about 800 miles to go before we got home, our father would pull up at an empty church on the way out of town.

He would send us in gently, telling us to ask God to “help us on the road.” After we came out, he would go in alone, taking off his hat before entering the church.

Soon, he would return and start the engine. We didn’t say anything until we were on the freeway again. Sometimes I was scared, wondering how we would all get home if the truck broke down. Somehow, we always made it.

This story appeared in print before the digital era and was later added to our digital archive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.