Column: California should allow its voters to fill U.S. Senate vacancies â not the governor

SACRAMENTO â Democrats accuse Republicans of trying to suppress voting all across America. But in California, Democrats actually ban voting to fill a vacancy in one of our most important offices: U.S. senator.

Thatâs hypocrisy, pure and simple.

For the record:

3:29 p.m. Aug. 10, 2020A previous version of this column said former Sen. Clair Engle resigned from office. He died while in office.

A Republican legislator is trying to fix the autocratic practice. But he hasnât a prayer with Democrats controlling both the legislative and executive branches of state government.

Of course, the GOP is equally guilty in other states â arguably even more sinful. Both major parties run elections in their own self-interests, regardless of what might be best for the public. Shock!

The recent Republican strategy, led by President Trump, has been to suppress voting among Democrats. The GOP does this by discouraging mail voting, claiming without significant evidence that it leads to voter fraud. Nonsense.

Republicans also push for voter photo IDs. They seek to reduce the time period for voting and the number of places to cast ballots. They aggressively challenge peopleâs eligibility to vote. Anything to hold down voter turnout.

The smaller the turnout, the larger slice of votes for GOP candidates, history shows. Thatâs because Republican voters tend to turn out more reliably than Democrats.

Thatâs why Democratic lawmakers donât trust voters in special elections to fill Senate vacancies. Special election turnouts are almost always much lower than in regular state elections. Democratic politicians are very happy to allow a Democratic governor to fill a Senate vacancy without voter interference.

And Republicans do the same thing in most states they control.

In all, 45 states authorize governors to fill Senate vacancies. In 36, including California, the appointee can serve the balance of the Senate term or until the next statewide general election.

But in nine, the gubernatorial appointee must face voters in an expedited special election. Thatâs the way it should be in California, at least.

Five states â Oregon, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Rhode Island and Wisconsin â require any Senate vacancy to be filled only by voters. Thereâs good precedent for this. Thatâs the way it is for the other half of Congress, the House of Representatives; also in the California Legislature.

Any vacancy in a statewide elective office, however, can be filled by the governor, subject to legislative confirmation. A governor is also empowered to fill vacancies on county supervisor boards.

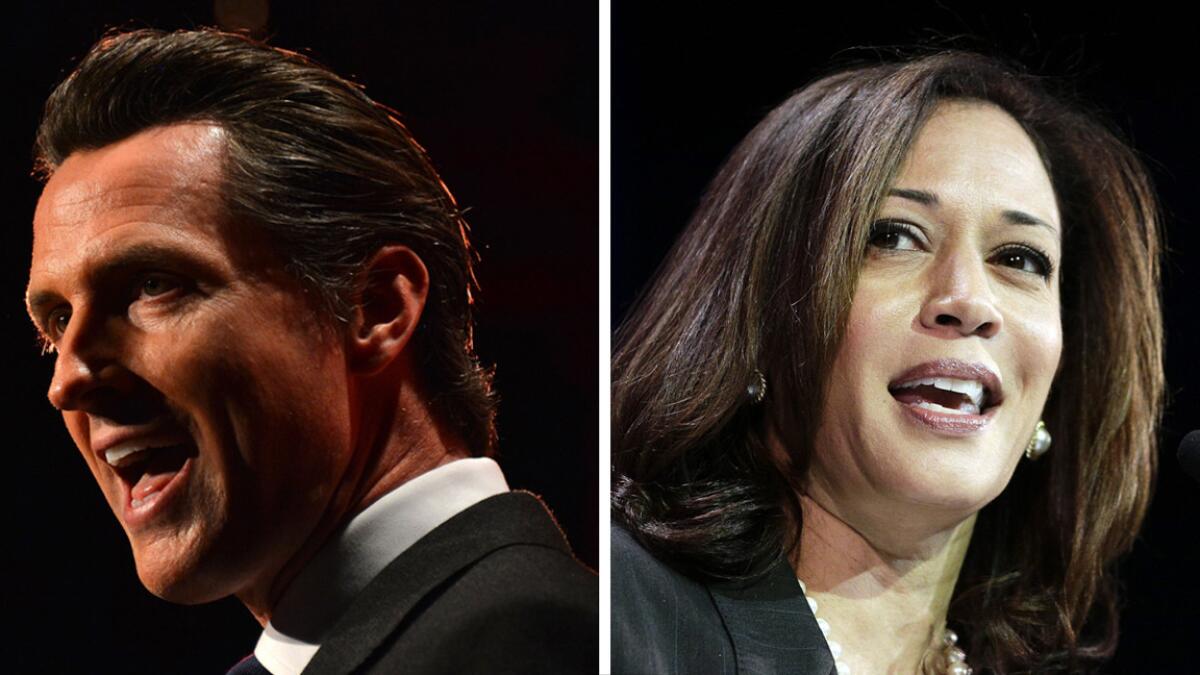

The issue of Senate vacancies arose when California Sen. Kamala Harris essentially began running for president about the time she was sworn into office after her 2016 election. Her candidacy flopped, but she immediately was placed on Joe Bidenâs short list of potential running mates.

There also was speculation in 2018 about whether Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein, who won reelection that year, would serve out her term. Sheâd be 91 when it expires. My bet is she will.

Republican state Assemblyman Kevin Kiley of Rocklin, near Sacramento, introduced a bill in 2018 that would have required the governor to call a special election to fill a Senate vacancy. It had one committee hearing and was killed on a party-line vote. Heâs back with a similar bill this year and it hasnât even been given a committee hearing.

âThe whole idea of our system of government is that the people should have a say in who their senators are,â Kiley says. âWith senators, itâs especially important because there are six-year terms with no term limits and they can stay in office for decades.â

âAppointments are an anachronism,â he adds. âItâs about time we bring our selection of senators into the 21st century.â

Until 1913, U.S. senators were appointed by state legislatures. The 17th Amendment required elections by voters. If thereâs a vacancy, the governor must call a special election. But thereâs a hitch: The Legislature can empower the governor to make a temporary appointment until the next election.

âThe ability of a governor to appoint a senator has been egregiously abused,â Kiley says, although not in California. Elsewhere, it has invited corruption and nepotism.

When Illinois Sen. Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, Democratic Gov. Rod R. Blagojevich was caught trying to sell the vacant Senate seat. He went to federal prison for eight years until Trump pardoned him in February. Thatâs the same Trump who had vowed to âdrain the swampâ of corruption in Washington.

Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska was appointed by her father, Frank Murkowski, who had resigned from the Senate in 2002 to become governor. In fairness, she did have some credentials as a state legislative leader.

In California, governors have appointed five senators to fill vacancies since the 17th Amendment was ratified.

In 1991, Republican Gov. Pete Wilson chose state Sen. John Seymour (R-Anaheim) to replace him in the Senate. Seymour was easily dispatched by Feinstein in the 1992 election.

In 1964, Democratic Gov. Pat Brown appointed former White House Press Secretary Pierre Salinger to replace Sen. Clair Engle, who died in office. Salinger was beaten that November by actor George Murphy, a Republican.

Republican Gov. Earl Warren made two Senate appointments: State Controller Thomas Kuchel to replace Sen. Richard Nixon, who was elected vice president in 1952, and William F. Knowland of an Oakland newspaper publishing family to fill in for Sen. Hiram Johnson, who died in office.

The fifth appointee was a brief office caretaker in 1938: Santa Barbara newspaper publisher Thomas Storke. He served two months and retired.

Thereâs a valid argument for not holding a special election to fill a vacant Senate seat. Itâs costly â around $100 million.

But democracy isnât free. California taxpayers send Sacramento enough money to foot the bill.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![[20060326 (LA/A20) -- STATING THE CASE: Marchers organized by unions, religious organizations and immigrants rights groups carry signs and chant in downtown L.A. "People are really upset that all the work they do, everything that they give to this nation, is ignored," said Angelica Salas of the Coalition of Humane Immigrant Rights. -- PHOTOGRAPHER: Photographs by Gina Ferazzi The Los Angeles Times] *** [Ferazzi, Gina -- - 109170.ME.0325.rights.12.GMF- Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times - Thousands of protesters march to city hall in downtown Los Angeles Saturday, March 25, 2006. They are protesting against House-passed HR 4437, an anti-immigration bill that opponents say will criminalize millions of immigrant families and anyone who comes into contact with them.]](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/34f403d/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1983x1322+109+0/resize/840x560!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fzbk%2Fdamlat_images%2FLA%2FLA_PHOTO_ARCHIVE%2FSDOCS%2854%29%2Fkx3lslnc.JPG)