LAUSD votes against proposal to defund school police and can’t agree on reform plans

- Share via

A deeply divided Los Angeles school board on Tuesday failed to agree on proposed reforms to the school police, effectively leaving the matter to a task force created by Supt. Austin Beutner and disappointing activists who had called for eliminating the department.

The lack of consensus capped a day of intense passions as students and activist groups called for terminating the department and using its $70 million annual budget for other student needs, especially those that would benefit Black students.

The school police had a smaller number of equally passionate defenders, including officers, social workers, school administrators and even a few students.

The Board of Education debate revolved around three resolutions.

The most aggressive was brought forward by Monica Garcia, who proposed phasing out funding for school police over the next four years. This was the proposal favored by activists critical of the police.

“This is not about you personally, Mr. Officer,” she said at one point. “This is about systemic racism and classism.” The district, she said, needed to transition away from a police department “to another safety strategy.”

“I do believe that we have the best school department in the country,” she said. “That is not enough.”

Only one of the six other board members, Nick Melvoin, joined with Garcia.

Nationwide, protesters and activists have been calling to “defund the police.” But what does it actually mean? And why are so many people calling for it to happen?

The proposal that seemed to have the best chance of passing was from Jackie Goldberg. It would have banned the use of pepper spray, cut the police budget by $20 million and imposed a hiring freeze, among other provisions.

She added the budget cut to her resolution to win the support of board members Nick Melvoin and Kelly Gonez. She also was willing to abandon the cut to win over board members, but no combination added up to the necessary four-vote majority.

A third resolution — to study the issue and provide recommendations to the board — had three solid votes from George McKenna, its author, Scott Schmerelson and board president Richard Vladovic.

“I think we need to be practical about what we’re doing rather than reactionary,” McKenna said. “Being loud doesn’t mean you’re right,” he said, referring to the day’s demonstration against police.

His resolution — which was favored by all three retired school administrators on the board — never had a chance at the fourth vote needed to claim a majority.

“If we don’t do anything today, it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do anything,” Goldberg said in resignation hours into the debate.

Anti-school police activists vowed to continue their efforts, calling Garcia’s resolution the “Freedom Motion.”

“All those who voted against the Freedom Motion lost and represent the racist past,” said Channing Martinez, director of organizing for the Labor/Community Strategy Center. “They cannot stop this moving bus.”

“I’m mad that LAUSD did not do anything about the ways that Black students are being policed,” said Dorsey High student Sarah Djato, an organizer for the youth-led group Students Deserve.

Juan Flecha, the head of the administrators union, was cautiously optimistic about striking the right balance between policing and students’ concerns after watching the day’s events.

“I have high hopes for the superintendent’s task force and appreciate that labor partners will be a part of the conversation,” Flecha said. “I’m happy there will be multiple perspectives. We do have to look at safety and budget matters and what police can do differently — what we all can do differently.”

He said it will be critically important to keep Black lives at the center of the conversation.

The decision came after contentious debate and passionate appeals from multiple sides of the issue.

Outside L.A. Unified headquarters, hundreds of students, activists and community members had rallied in the morning to demand that the school board eliminate the school police department. On the ground, they waved signs and danced to music about police brutality. Above, a sky-writing plane spelled “Defund LASPD.”

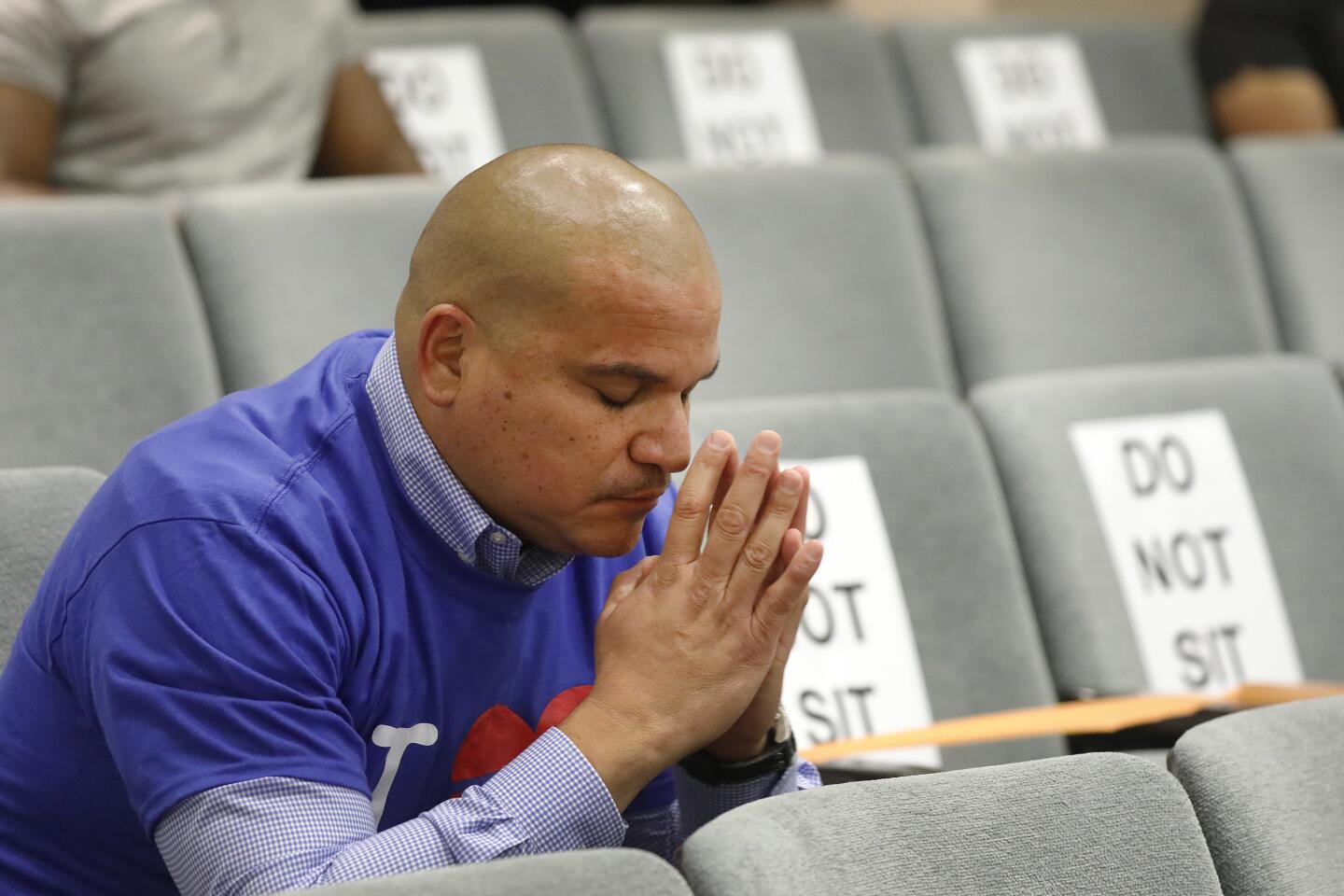

Inside the boardroom, almost all the 25 available, socially distanced seats were occupied by off-duty school police or their supporters. The only board member there in person was Garcia, who authored the resolution to defund school police by 90% within four years. It would have redistributed funding according to a formula that ranked schools most in need.

Public speakers overwhelmingly voiced support for Garcia’s resolution, but many parents, school employees and police officers defended the department, referring to officers’ experiences risking their lives to keep students safe and building community relationships.

“School police does not make us any more comfortable,” said Amara Abdullah, co-founder of the Black Lives Matter Los Angeles Youth Vanguard and a rising freshman at Hamilton High. “You can’t expect us to do as well in school as white students if we feel criminalized every time we walk into campus.”

Mya Edwards, a recent Venice High School graduate, echoed Amara.

“Black students feel criminalized, have been pepper sprayed, arrested. What else do you need?” Mya said. “Do you want an accidental death like George Floyd’s? Do you want to see that on campus?”

Garcia’s plan had backing from activist groups, students and community members who’ve long called for defunding the school police. The California Charter Schools Assn. and the leadership of the two largest L.A. Unified unions, representing teachers and most non-teaching workers, including bus drivers and classroom aides, also backed Garcia’s resolution. The leadership of other employee unions, including the one representing principals and other administrators, wants to keep the school police.

“We should be changing together, not be against each other,” said L.A. School Police Sgt. Nestor Gonzalez, a district graduate who said he felt betrayed by Garcia. “I’m about to lose my livelihood, my insurance, my way of living here in Los Angeles” and students, he asserted, would be less safe.

Lakisha Johnson, a psychiatric social worker who works with the police department’s mental health response team, said that as a Black woman she understands the issue of institutional racism and the need to root it out assertively. But the school police, she said, are being unfairly scapegoated.

She called for every division, “because we have all collectively failed Black students over the past several decades,” to relinquish 5% of their budgets, making every unit accountable “to move the meter” and if they don’t, reallocate the budget to departments that are making a difference.

The L.A. School Police Department, founded in 1984, employs 366 sworn officers and 95 non-sworn officers. It is one of the largest school police departments in the country — behind that of Miami-Dade Schools Police, which employs 455 sworn and 75 non-sworn officers, according to an L.A. Unified analysis.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.