- Share via

When Adam Bratt studied the faces of his Advanced Placement psychology students that morning in December, he saw trauma.

Little blue ribbons fluttered outside, and therapy dogs zigzagged through Saugus High School’s solemn campus. In his classroom, Bratt locked eyes with his students, telling them he’d had a fulfilling career, and he wasn’t going to let the Nov. 14 shooting on their Santa Clarita campus define him.

“You shouldn’t either,” he assured them.

He pulled up a PowerPoint presentation and flipped to a slide labeled “The Game of Life,” where he’d created a collage of 33 things that his students, many of them seniors, had to look forward to.

“Leaving a family home,” one read.

“Falling in love.”

“Going on an ice cream date with your kid.”

That evening, when several students emailed asking for a copy of the PowerPoint, none could know that their opportunity to cross an item off the list — “Bearing witness to a turning point in history” — would arrive in a few months in the form of a global pandemic.

Born in the panicked days after 9/11 and into the dire reality of an increasingly inhospitable planet, the high school class of 2020 has become a cohort bookended by two generation-defining tragedies. They will soon graduate — most of them virtually — into a world whose routines are defined by a deadly disease and an economy potentially decimated to levels never before seen by their parents or even many of their grandparents.

‘Our safe, quiet town lost that title yesterday. Now we’re just another statistic.’

— Note placed at Central Park

“We’ve really gone through it,” said senior Megan Puettmann, one of the editors in chief of Saugus’ yearbook, who in the hours after the shooting tweeted, “When will this stop? #EnoughIsEnough #GunControl,” then spent the day after her classmates were gunned down thoughtfully responding to people tweeting at her that guns weren’t the problem.

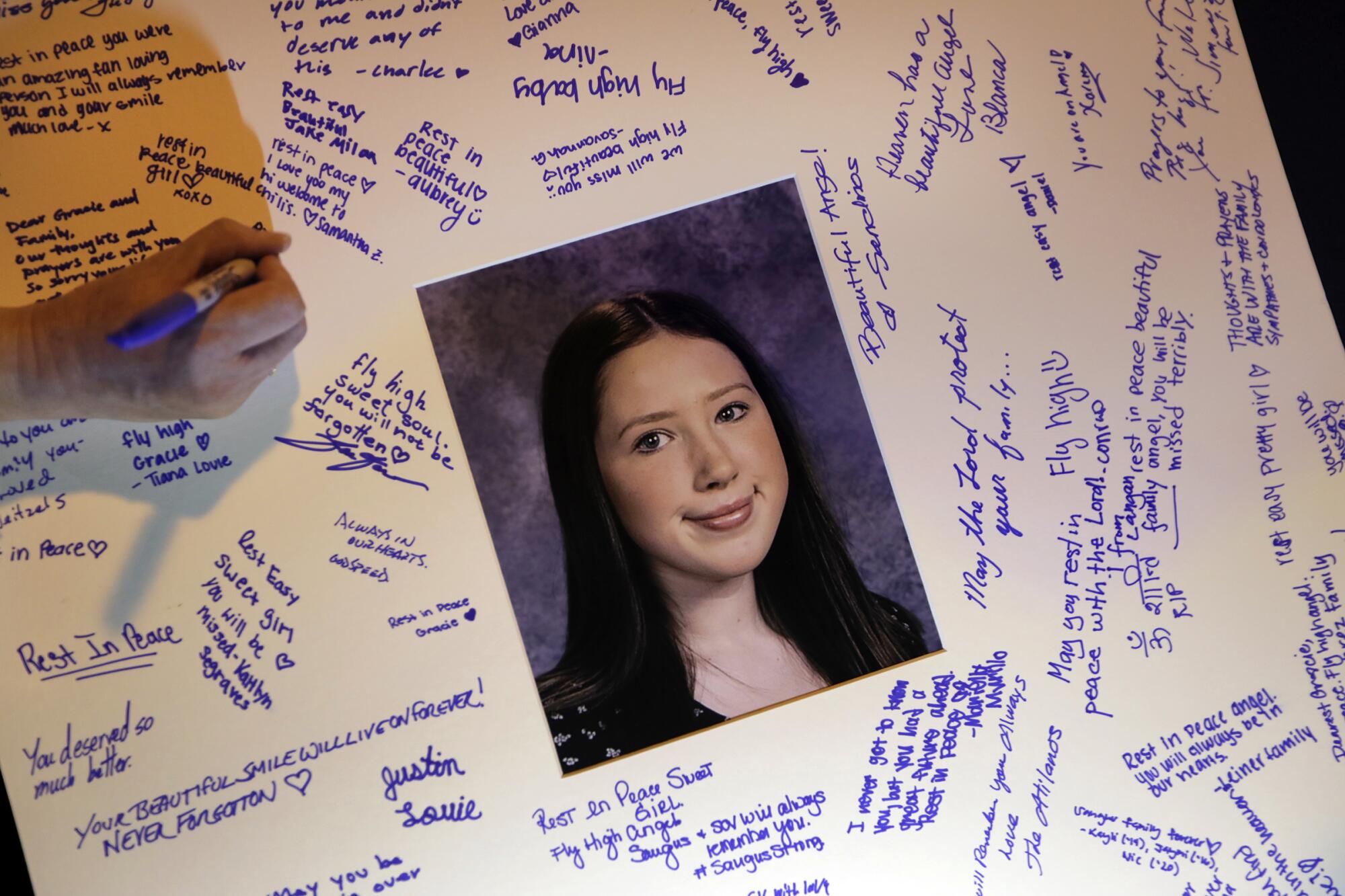

When the pandemic shut down several end-of-senior-year traditions, Puettmann said, it only compounded the still-raw feelings of loss from that morning in November, when a student pulled a handgun from his backpack and shot several classmates, killing Dominic Blackwell, 14, and Gracie Anne Muehlberger, 15, before turning the gun on himself.

The slayings stunned Saugus students and confounded Santa Clarita’s sense of itself. That week in Central Park, just down the street from campus, someone left a note in blue ink:”Our safe, quiet town lost that title yesterday. Now we’re just another statistic.”

At first, Puettmann dreaded returning to campus after the shooting, , fearing she’d flash back to the image of backpacks abandoned on the floor. But she eventually returned, buoyed, in part, by anticipation for the next few months — attending prom, laying her hands on the yearbook she’d helped create, trying for a personal best in the 100-yard fly at swimming competitions.

Then came March 13.

That Friday afternoon, when Saugus students learned that they’d be out of school for three weeks because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the news came as a welcome relief to many. An extended spring break, they thought, a breather. A chance to start social distancing so they could all be back by graduation.

Andrei Mojica, Saugus’ student body president, said he initially relished the opportunity to chill and catch up on homework. But he was monitoring the news, and his parents work as registered nurses — his mother in an ICU — so reality quickly settled in. There would be no senior night for his lacrosse team, he realized, no more In-N-Out Burger hangs with his friends.

“School just ended on a random Friday in March,” Mojica said, sighing and explaining that, although he’d planned to attend the University of Washington, he recently made the difficult decision to waive his admission, given the cost and the uncertainty during the pandemic. For now, he said, he will study political science at the College of the Canyons in the fall.

Now that he knows he won’t return to Saugus, he wishes he had packed more into those last few weeks on campus — that he’d savored the last walk through the halls of the school that taught him about resilience and grit and empathy.

It feels like losing that tiny sliver of your life when the unencumbered lightness of childhood momentarily overlaps with the freedoms of adulthood. That time, Mojica said, when you can drive yourself anywhere you want to go, but you’re not yet too worried about student debt.

Time to swap yearbooks and scrawl earnest things you’ve never told each other in person and to gather for “senior sunset,” when you roll out blankets and watch the glow melt into the horizon together.

On March 19, the day Gov. Gavin Newsom issued a statewide stay-at-home order, senior Priscilla Arguelles pulled out her journal.

“i am so sad for my class 2020,” she wrote, “not being able to have prom or graduation, or just having our last few moments with friends and teachers we could never see again.”

Missing prom, in particular, bummed her out. She already had a date, her best guy friend, and she had bought her dress, a red gown with an open back and a sparkly top, five months earlier, determined to wear something unique. Most of all, she was excited to take photos with all her friends. She’d gotten close to many of them this year, she said, and it felt especially lucky after mostly keeping to herself junior year.

But the biggest disappointment for her and many of her classmates is graduation.

For years, Olivia White, one of Arguelles’ friends, had envisioned that moment onstage when she would turn to look at her mother and father and grandmother in the crowd and beam beneath her white cap, a sign that she’d graduated with honors.

“It’s every kid’s dream,” she said, adding that even though the school is planning a virtual graduation in June, she hopes there’s a chance for an in-person ceremony in the future.

On the day she found out she would finish her senior year online, White, not one to cry in front of others, went to her room and sobbed. She thought about how fiercely she had wanted to avoid campus after the shooting and how completely she wanted to be back there now.

She felt heartsick for people losing loved ones to the virus, and she felt anxious about her parents getting sick. She thought about the economy — about people whose parents now couldn’t afford to help pay their college tuition and about how hard it would be for classmates who weren’t going to college to find a job this summer. She thought about her fellow seniors and the year they’ve had.

“We really didn’t get any good luck.”

* * * * *

Many Saugus seniors see their final year on campus in two distinct chapters: before and after the shooting.

On Nov. 12, Mojica retweeted rapper Lil Nas X, lightheartedly asking why, exactly, Clifford the Big Red Dog was so big. His next tweet, two days later, was encouraging everyone to hug their loved ones tightly.

“I love you all,” he wrote. “Let’s stick together, Centurions.”

Around 7:30 a.m. on Nov. 14, someone swung open the door of his AP government class to say there was a shooter on campus. Terrified, Mojica grabbed a fire extinguisher and stood near the door.

In another classroom, White was correcting a math worksheet when students ran inside screaming, “School shooter!” She figured it was a false alarm like the one from freshman year. But then a voice boomed over the intercom telling them to lock the doors and get down. At 7:43 a.m., while hunched on the carpet in the back of her classroom, she gripped her phone.

“hey mom,” she texted. “there is a shooter on campus.”

“Omg,” her mother responded.

“one student got hit.”

“Ok stay hidden.”

In a different classroom, Arguelles heard what she thought was a drum dropping in the nearby music room, but then she watched her teacher sprint to lock the door. Arguelles’ body started shaking, and she could tell she was wailing louder than anyone else in the classroom. She clasped her hand over her mouth, and two words echoed in her mind: “It’s happening.”

Nearly three weeks later, after vigils and funerals and Thanksgiving, they returned to campus, forever changed. If they listened to music while studying, they left one earbud out. Whenever a silhouette whirred outside a classroom window, everyone’s heads swiveled in unison.

One morning in the middle of January, as they were beginning to get back into a groove, someone drove a school golf cart over a plastic water bottle, creating a loud popping sound. Muscle memory kicked in, and students dropped their backpacks and ran.

Senior Carli Chorpash was still in her car when she saw a group of students running from campus. Not again, she thought. Even now, the sound of a trash-can lid slamming shut sometimes spooks her, and on Super Bowl Sunday, when she heard several loud pops — they turned out to be fireworks — she started crying, convinced there was a gunman on her street.

She has learned that healing from trauma isn’t linear. Sometimes she goes a full week without thinking of the shooting, but the next week she thinks about it every day.

“You have to be gentle with yourself,” she said. “There’s really no guidelines on how to heal from this.”

On the morning of the shooting, Bratt, the AP teacher, was pulling into a parking lot on a hill when he saw students sprinting toward him. In nearly 30 years of teaching, six of them at Saugus, he had guided students through the days after 9/11, earthquakes and fires. All those tragedies had hit close to home, he said, but now one had hit home.

He later returned to that hill and listened to music for a couple hours. He was OK, he realized, and now he needed to focus on his students. He became obsessed with finding ways to keep them connected to their education. He still saw sadness in their eyes some days, but mostly he saw resilience.

Sometimes a student who had skipped a test a few days earlier would email him or come up to him in class, determined to catch up.

“Bratt, when can I take the exam?” they’d ask.

“You tell me!” he’d respond.

He wouldn’t always have reacted that way, he said. But teaching, like life, is about learning to pivot. In his class, they spend a lot of time talking about divergent thinking, about coming up with multiple solutions to a problem. And this year’s seniors, Bratt said, will no doubt grow into some of the most divergent thinkers he’s ever taught.

“Do a longitudinal study,” he said, proudly. “Some of these kids are going to have the highest emotional intelligence you’ll ever see.”

Toward the top of Bratt’s “33 things that still lie ahead” PowerPoint from December, there was an entry in curling green letters: “Graduating from school.”

But below that, in smaller font, a more universal adventure:

“Experiencing disappointment.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.