California is way behind in testing and tracking coronavirus. It’s a big problem

- Share via

In the race to expand testing for the novel coronavirus and track the results, California has fallen behind New York and other hot-spot states as an assortment of public and private groups pursue testing programs in an uncoordinated fashion.

A fragmented landscape akin to an orchestra playing without a conductor has emerged with public officials at the city, county and state levels scrambling to come up with testing options and priorities. At the same time, various universities and an increasing number of private, for-profit labs have developed their own testing schemes.

The result has been a confusing, incomplete picture of the virus in California.

Public health experts warn that a robust, coordinated testing program is crucial so the state knows not only who is infected but how quickly and where the virus is spreading in order to effectively deploy limited resources, such as protective equipment, ventilators and medical staff.

“We are cobbling together various approaches,” said Susan Butler-Wu, an associate professor of clinical pathology at USC’s Keck School of Medicine and a director of a clinical microbiology lab in Los Angeles. “The whole thing is badly discombobulated.... I think 100% that the system is broken.”

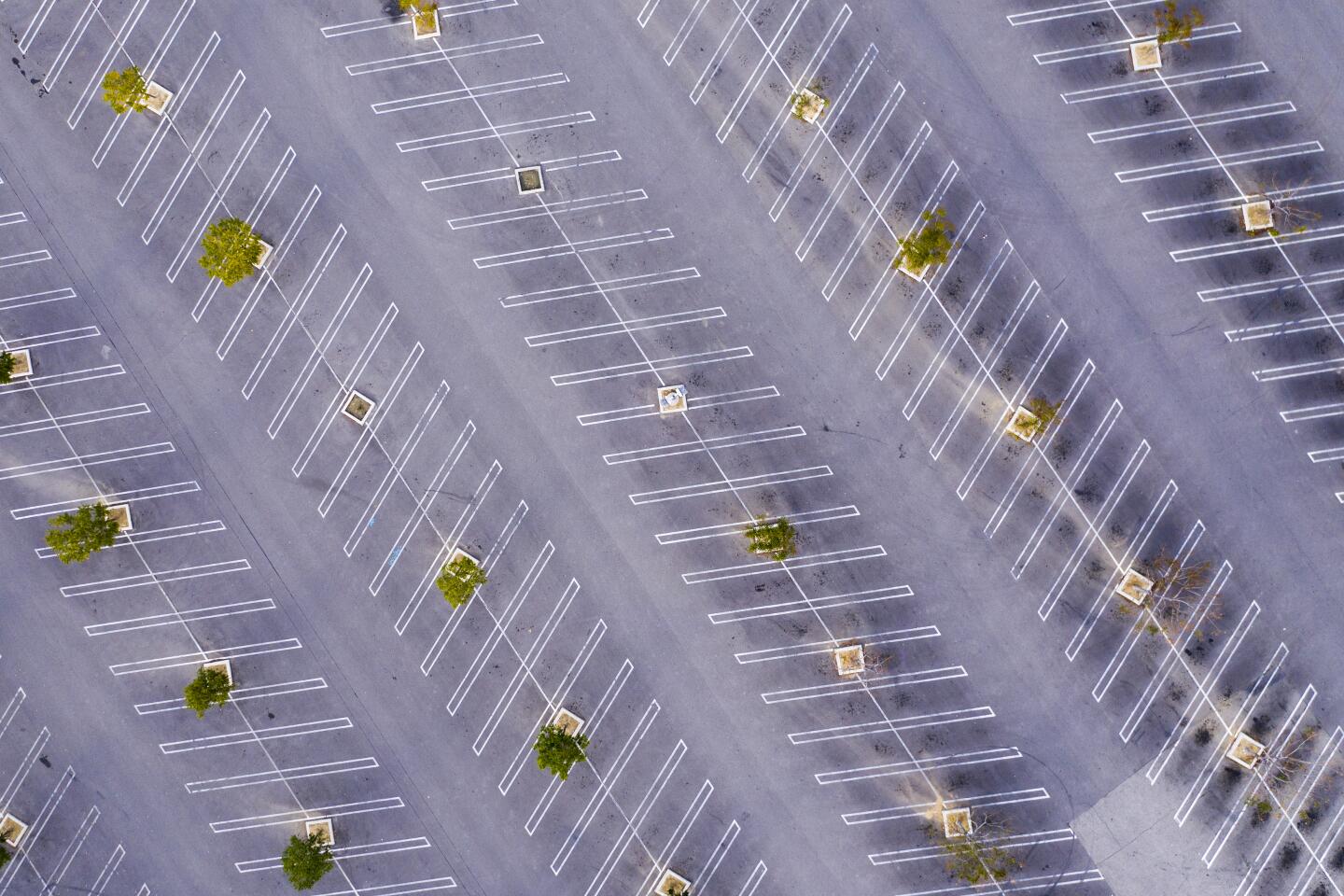

Gov. Gavin Newsom has ordered Californians to stay at home. With businesses and popular destinations closed, The Times’ Luis Sinco documented the surreal scenes.

Certainly, Butler-Wu said, California is not alone, as the failure of federal health officials to establish a coordinated, nationwide testing strategy has given rise to a similar mishmash of testing options around the country. The impact, however, has been particularly blunt here, where the sheer size of the state and the large number of testing operations have exacerbated the problem.

In California, there are at least 22 state laboratories, seven hospitals and two private outfits conducting tests. It is unclear how testing at those sites is being tracked, in part because Gov. Gavin Newsom has not provided details.

Newsom said Monday that part of the problem has been an inability by the state to accurately collect all test results. He has deflected, however, questions about California’s overall testing capacity and whether it could have ramped up more quickly.

By Sunday afternoon, approximately 26,400 tests had been conducted in the state, which has about 40 million people, according to the state’s official tally. The total was an increase of just 200 tests from the day before.

By contrast, New York, which has half as many residents and is grappling with the nation’s largest number of COVID-19 cases, had performed more than 78,000 tests as of Monday, according to the COVID Tracking Project, an independent group.

Based on population size, California’s official test numbers are not at the bottom of the state rankings, but it is below the national average of nearly 90 tests performed for every 100,000 residents, according to a Los Angeles Times analysis of testing numbers tracked by the group. California also lags behind other states that have experienced large outbreaks of the virus, including Louisiana and Washington.

The United States as a whole was slow to ramp up testing for the virus after a test designed by the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was found in early February to be flawed. Federal regulators then kept other labs from designing and using their own tests until Feb. 29, when they belatedly relaxed their rules.

Since then, dozens of companies as well as public and private labs have designed tests. But laboratories have struggled to process the sudden surge in demand.

In light of those backlogs, as well as shortages of materials needed to perform the tests, county health officials and hospitals around the state have largely stuck to guidelines from the CDC that reserve tests for those showing symptoms of the virus and at highest risk of contracting it.

California’s landscape of everyday life is changing under the state’s stay-home order. These drone photos prove it.

Universities and other healthcare networks, such as UCLA, UC Davis and Kaiser Permanente, have developed their own tests, although the number being performed remains relatively small.

And local authorities across the state have been left to try to boost their own capabilities. Los Angeles County announced Monday it has secured 20,000 tests with a processing capacity of 5,000 tests per day. The kits will be free, and healthcare workers and first responders will be given priority for testing.

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced a smaller testing program Monday for the city that will focus as well on first responders, but will also test some residents considered at high risk of becoming infected. L.A. Councilman David Ryu said city officials are in talks with a South Korean company that could make tens of thousands of tests available.

“There are not enough supplies to meet the demand,” Butler-Wu said. “It’s basically every system or hospital for itself and that is not what you want for a pandemic.... You need a coordinated system that is rolled out across the state, across the county.”

This piecemeal approach, said Harvard epidemiologist Michael Mina, is a key problem with testing in California and nationwide.

“We have a decentralized healthcare system and we have no way to scale for government means,” Mina said. “Everything is privatized, everything is individualized in our country and it’s become our Achilles’ heel in this case.”

On Monday, when he was asked why fewer people are being tested in California compared with New York, Newsom said the state’s numbers do not include all tests being conducted.

“We have a number of different test protocols that are underway that are not part of the 26,400 number that you received this morning,” Newsom told reporters.

The governor said the state would release more accurate figures on Wednesday that include data from more facilities now conducting tests. The new number, he said, “will substantially increase” the current totals.

Newsom said as the state moves to increase testing, it will focus in part on community surveillance to better understand the scope of the crisis.

“The bottom line for us is we want to know what the spread is,” Newsom said Saturday. “We want to know if we’re bending the curve. We want to know if our stay-at-home orders are effective. That’s fundamentally the point of testing in terms of the broader sample.”

Mina echoed the importance of this approach, saying, “We are flying blind through this tunnel at the moment, and we don’t know where we are in the epidemic curve.”

Newsom said the state has conducted so-called community surveillance testing in Santa Clara, Los Angeles and Orange counties. The governor said the tests have been “very helpful” and he expects to expand them throughout the state, but did not say what the tests had found.

Among the fragmented snapshots California is gathering are drive-up testing programs now in four counties, through a state partnership with a subsidiary of the Google tech empire. The first week the project tested 1,200 people, prioritizing healthcare workers and initially including some people with no virus symptoms. The state expanded the project over the weekend to Riverside and Sacramento counties.

Conducting random sample tests, Newsom said, will not supplant traditional tests for people who show signs of infection or work in jobs with a high risk of exposure to the virus.

But with resources so limited, the two needs are in competition with each other. While the governor is charged with protecting the broader health of the entire state, doctors are trying to treat patients and protect themselves. With the lack of available tests, the two responsibilities are colliding.

That collision is playing out especially in hospitals in the Bay Area and Los Angeles, which have the highest numbers of infected people.

At L.A. County-USC Medical Center, for example, the slow pace of testing is exacerbating shortages in safety equipment medical staff wear to guard against becoming infected. When it’s not clear someone with respiratory problems has COVID-19, staff members have to behave as if they do, which means doctors, nurses, support staff and cleaners can waste precious protective gear while awaiting test results.

As of Friday, the turnaround time for tests was between five and seven days, a spokeswoman for the county Department of Health Services said. In an effort to find a work-around, the county has purchased equipment to perform in-house testing, but is still a few weeks away from being able to do so, she said.

Times staff writer Harriet Ryan contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.