San Diego faces critical earthquake danger from fault long believed to be inactive

- Share via

SAN DIEGO — The conventional thinking has long been that the San Diego region faces less danger from a devastating earthquake than the Los Angeles or San Francisco areas.

But a new landmark study shows just how a fault running through the heart of San Diego poses a much more serious threat than believed a generation ago.

Researchers examined the effects of the Rose Canyon fault producing a plausible magnitude 6.9 earthquake, threatening the civic and financial center of California’s second-largest city and the nation’s fourth-biggest naval base, and causing liquefaction and landslides.

Such a quake could damage 120,000 of San Diego County’s 700,000 structures and cause $38 billion in economic losses from building and infrastructure damage and $5.2 billion in lost income from business interruptions, according to a report released Wednesday by the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute’s San Diego chapter on the first day of the National Earthquake Conference at the Sheraton San Diego Hotel & Marina.

San Diego could be disrupted for years. Yet most people in San Diego either know nothing about the Rose Canyon fault or think it’s still not active, even though it has been 30 years since experts confirmed it was not dormant, said California Seismic Safety Commissioner Jorge Meneses, president of the institute’s local chapter and a geotechnical engineer.

“This type of mentality needs to change,” said Meneses, whose organization has been working on the report for five years. “We have a seismic source here, running through downtown.”

Particularly troubling is that for many decades the San Diego area was built to lower seismic standards than the ones applied to L.A. or San Francisco, based on the belief that San Diego had a lower seismic risk.

It was only after the discovery of the Rose Canyon fault’s activity that the minimum building codes for this region were raised to Seismic Zone 4, the highest level and the same as that of Los Angeles and San Francisco, said Heidi Tremayne, executive director of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, a nonprofit based in Oakland.

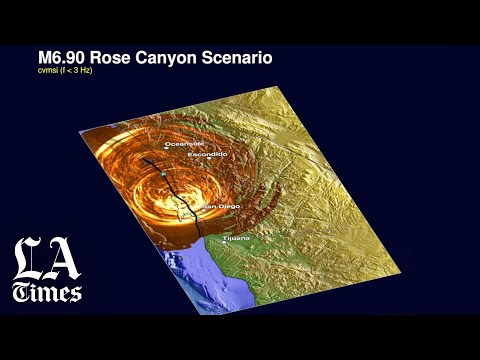

Violent shaking would ripple through the Rose Canyon fault in a hypothetical magnitude 6.9 earthquake in the heart of San Diego. (Earthquake Engineering Research Institute / USGS)

“Many older, more seismically vulnerable buildings constructed before modern seismic design provisions were in place, including several key City of San Diego facilities, may be severely damaged with multiple older buildings potentially suffering partial to total collapse,” the report said. It did not specify which buildings.

There could be many deaths, as the San Diego region has relatively weak local laws requiring retrofits of vulnerable buildings compared with cities like Los Angeles and Santa Monica. The San Diego region is estimated to have thousands of apartment buildings with flimsy ground floors, hundreds of potentially brittle concrete buildings that can be particularly deadly if they collapse, and scores of possibly vulnerable steel-frame office and hotel buildings.

None of the buildings described above are required to be retrofitted in the city. And for another particularly deadly class of buildings, old brick buildings, San Diego required only limited partial retrofits, the report says.

The Northridge earthquake that hit 25 years ago offered alarming evidence of how vulnerable many types of buildings are to collapse from major shaking.

The authors expressed great concern that the collapse or damage of these old brick buildings — which have been ordered retrofitted or demolished in other cities like L.A. — would dramatically worsen emergency response. Several hundred of them are believed to remain in places like downtown San Diego, National City, Chula Vista, El Cajon, Solana Beach, Encinitas, Oceanside and unincorporated areas of the county.

Many of San Diego’s civic institutions may end up being crippled, including police and fire stations and city offices, as first responders are called to perhaps hundreds of fires. The researchers estimate that nearly half of county schools and hospitals could be running at partial capacity for days.

Military facilities around San Diego Bay would suffer from severe ground shaking and liquefaction. And more than 100,000 residential structures could be damaged — many of them apartments — worsening the affordable housing crisis.

And with land on the western side of the fault lurching to the northwest relative to the eastern side, many pipelines, cables, bridges and railroads could be severed or otherwise disrupted. Water, wastewater and gas lines serving areas west of the fault, from La Jolla through Coronado, could be cut off for months after the quake. Coronado firefighters could find themselves without functioning water pumps to fight fires.

San Diego International Airport could find itself hamstrung as land underneath it acts like quicksand when shaken, damaging the runway, taxiways and buildings. A western section of the fault passes directly under the runway, and a quake would render it temporarily inoperative.

Gas line breaks and a loss of water pressure would make firefighting even more difficult.

And although the Coronado Bridge has been retrofitted to withstand collapse, experts said they expect land on one side of the fault to lurch two to three feet from the other side. Damage could render the bridge unusable for weeks, months or possibly years.

For decades, there had been no scientific work done demonstrating the Rose Canyon fault was active. Then, in 1985, the first hint appeared during an excavation at Broadway and 14th Street, where a section of the active fault was discovered, said Tom Rockwell, professor of geology at San Diego State.

The big discovery came in 1990, when trenches were dug across the fault in Rose Canyon. It showed the land on the western side of the fault had lurched to the northwest 30 feet over various earthquakes in the last 8,000 years, convincing evidence that the fault was alive, Rockwell said.

Today, it’s believed the Rose Canyon fault ruptures in a big earthquake of something approaching a magnitude 7 about every 700 years — give or take 400 years or so. The last such major quake is believed to have happened between 1700 and 1750, Rockwell said, before the Spanish founded their first California mission in San Diego in 1769.

Between those big quakes, quakes in the range of magnitude 6 can strike. Such a quake ruptured on the fault right through Old Town in 1862, causing what the Los Angeles Star declared the “Day of Terror” in San Diego, Rockwell said.

Today, it’s known that the Rose Canyon fault is actually the southern continuation of the Newport-Inglewood fault, which caused Southern California’s deadliest earthquake on record, the magnitude 6.4 Long Beach earthquake of 1933 that killed 120 people.

(It’s possible the Newport-Inglewood/Rose Canyon fault system could rupture in the same earthquake, from the Westside of L.A. through Long Beach to San Diego, in a single earthquake. The energy released from that quake would be rated magnitude 7.4.)

Without a major change in San Diego’s psyche about earthquakes, the city could end up facing the fate of the city of Christchurch, New Zealand.

Many people in Christchurch also thought of themselves as relatively safe from earthquakes, as the city was also quite a distance from the South Alpine fault, the South Island’s version of the San Andreas fault.

So when a magnitude 6.3 quake ruptured under the city in 2011, the damage was catastrophic: The central business district downtown was left in ruins and 185 people died, mostly from the collapse of unretrofitted brick buildings and two brittle concrete buildings.

Christchurch, New Zealand, shattered by a 2011 earthquake, offers an urgent lesson for California.

“Having spent a decade working down there and knowing how people felt about the risk before and now, this is still such a shock to them,” said Laurie Johnson, the president of the research institute and an urban planner.

San Diego can avoid this future if there’s a concerted regional effort to retrofit vulnerable buildings and infrastructure before such a quake hits. The authors recommend a committee of government officials, earthquake experts, utilities and others to identify county seismic hazards and suggest actions.

“Without that advanced mitigation work, we are worried it could jeopardize the economic vibrancy of the region,” Tremayne said.

San Diego County’s chief resilience officer, Gary Johnston, said officials across the region should consider establishing such a group to focus on “a deliberate plan to address seismic resiliency.”

Strengthening the region against quakes is part of the bargain of living in San Diego.

“We owe a lot of the beauty of San Diego to the Rose Canyon fault,” from the fault pushing up Mt. Soledad by La Jolla to the creation of the bays of San Diego, Rockwell said, enabling it to be the principal home port of the Navy’s Pacific Fleet.

“If we did not have the Rose Canyon fault, then we would look like Oceanside. It’d be a long, linear coastline with not much going on,” Rockwell said. “Because the fault line comes on shore in San Diego, it produces the topography that makes San Diego unique.”

At a panel discussion after the release of the report, Ali Fattah, senior research engineer for the city of San Diego, said there would be challenges in strengthening vulnerable buildings. San Diego is already undergoing a big building boom, and city workers have more work than they can handle, “so we’re actually starved for resources in terms of current staffing levels,” he said.

“It’s easy to get rules out there,” Fattah said, but the city doesn’t have the resources right now to create an inventory of vulnerable buildings. He also suspects residents will be opposed to the city imposing strengthening requirements on old buildings.

Other cities in California have managed to create inventories of problem buildings and order retrofits after convincing residents and businesses that the regional economy was at risk if nothing was done. Los Angeles created a list of 15,000 potentially vulnerable apartment and brittle concrete buildings, and San Francisco, about 5,000 apartments, and ordered them to be retrofitted.

Fattah said he found some of the study’s findings surprising. “I live in the coastal zone. I was not aware that we could potentially, for three to four months, have no water and sewer.... How would I live without water and sewer and electricity?” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.