For stranded sea otter pups, Long Beach aquarium expands its fuzzy mama foster program

- Share via

Each year, a handful of stranded or orphaned sea otter pups are placed into a sort of fuzzy foster care.

At the Monterey Bay Aquarium, rescued babies are paired with the facility’s female otters, who take them in, care for them and show them the ropes.

The goal is that the pups will learn all the skills they need to survive in the wild — without developing a reliance on humans.

While officials say the surrogacy program has been effective, there’s one significant hurdle: capacity.

That’s where Long Beach’s Aquarium of the Pacific comes in.

The two institutions officially announced a partnership Thursday to expand the surrogacy program across the state.

“It’s just so exciting to step into our role and be on the front lines of this conservation work,” said Brett Long, curator of mammals and birds at Aquarium of the Pacific.

Increasing the surrogate program’s capacity is imperative to help with sea otter recovery along the California coast, he said.

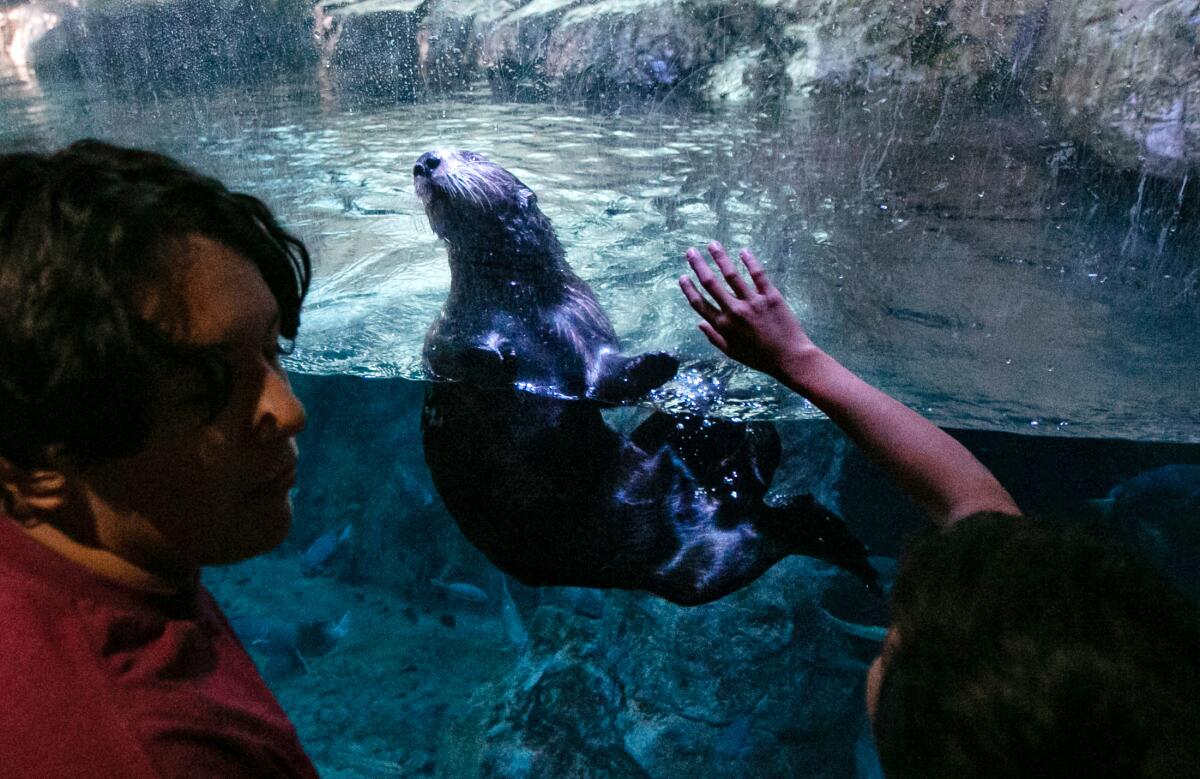

In announcing the program, Aquarium of the Pacific also unveiled its newest resident: a 4-year-old otter named Millie, who officials say is a prime candidate to serve as a surrogate mom.

After all, she’s already raised a pup of her own.

“We know that she was a very good mom, so she’s a very likely candidate to be a good surrogate,” Long said.

Monterey Bay Aquarium has been using otters as surrogate mothers to great effect since the 1990s, according to Kyle Van Houtan, the institution’s chief scientist.

The idea came about somewhat by chance. The aquarium came into possession of both a female otter that had just lost a pup and a pup that had been orphaned.

“We said, ‘Hey, we have peanut butter and we have chocolate here, can we make a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup?’ ” Van Houtan said.

Otters, he said, “have a prolonged maternal care attachment, and the dependent pup is completely dependent upon the mom.”

“They have to be taught how to do certain core functions like foraging for food and hunting,” Long said. “That’s something the mother sea otter teaches.”

If something happens to mom, “that pup is completely lost on its own, and there’s no social organization like there would be in a whale pod to pick up the slack,” Van Houtan said.

“We realized, ‘You know what? The otters are better moms than we are,’” he said. “Even though it is possible to rehabilitate an orphaned pup, if you do it just with humans, then that otter really can’t go back into the wild.”

The results so far seem to back up that thinking. A recent study found that surrogate-raised otters and their wild offspring have played a significant role in growing the population at Elkhorn Slough, an estuary in Monterey Bay.

However, surrogacy is a logistically demanding and time-consuming process — it typically takes about eight to 10 months — meaning Monterey can accommodate only five pups or so in a given year, according to Van Houtan. Aquarium of the Pacific, he said, was a natural choice for a partner.

Aquarium of the Pacific is developing a new surrogacy area, which officials hope eventually will accommodate three or four rescued pups a year.

That area will be designed to limit human influence on the otters, Long said. That’s vital, wildlife officials say, so the otters don’t become reliant on humans.

At Monterey, for instance, workers who feed otter pups when they first arrive do so in disguise so the animals won’t come to associate humans with food, Van Houtan said.

“We call it the ‘Darth Vader’ outfit,” he said. “It looks like you’re going to go weld something.”

Although California’s sea otter population has rebounded over the decades and now sits at almost 3,000, the species is still threatened and faces significant risks from things like oil spills, pollution and the effects of climate change, Long said.

Otters also only occupy a relative sliver of their historical range.

Growing the wild population isn’t just good for the otters themselves, it’s also a boon for the environment. Van Houtan said otters are a keystone species, meaning they have a significant positive impact on the ecosystem.

“Our whole goal is that the otters win, and our whole goal is that the coastal communities and coastal ecosystems win,” Van Houtan said. “And for that to happen, we need to expand this program.”

For more information, or to donate to support the program at Aquarium of the Pacific, visit aquariumofpacific.org or call (562) 951-1701.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.