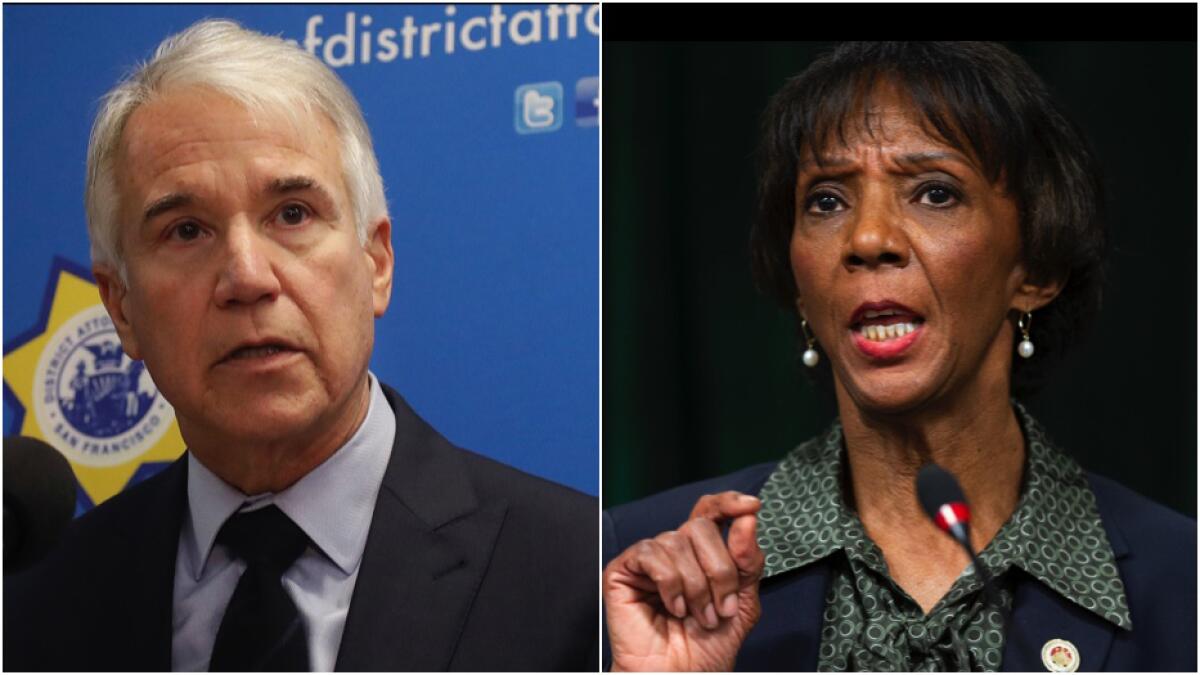

Police unions, justice reformers battle for dollars in bitter L.A. County D.A. race

- Share via

For most George Gascón supporters knocking on doors in South Los Angeles, the race to determine the county’s top prosecutor is extremely personal.

Among those involved in the $1-million get-out-the-vote effort is Linda Gomez, who as a teen was sentenced to 14 years in prison for assault with a gang enhancement. She was released after criminal justice reform laws such as those championed by Gascón changed parole eligibility for juvenile offenders.

For the record:

4:29 p.m. Feb. 24, 2020An earlier version of this article misstated the amount of donations collected by Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. candidate George Gascón and when he entered the race. Gascón announced his candidacy in October and has amassed $341,000 in direct fundraising.

“At 17, I just remember sitting in that courtroom scared to death,” she said. “Most girls are getting ready for prom or SATs, and I’m looking at spending the rest of my life in prison.”

Just a few miles away, near downtown, is the Los Angeles Police Protective League, the union representing rank-and-file LAPD officers that has long supported more traditional law-and-order policies, which poured $1 million into two outside committees supporting L.A. County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey.

An outside committee organized by the union recently released an ad depicting Gascón as a “con man” scurrying out of San Francisco to escape criticism for his alleged failings as district attorney there.

As the combative district attorney’s race hurtles toward a March 3 primary, the ideological split between Lacey and her two challengers is starkly represented by the people and organizations pumping a combined $4.3 million into the race through contributions to outside committees.

A Times analysis of public records found that nearly all of the $2.2 million in contributions to outside committees benefiting Lacey has come from law enforcement unions, while three-quarters of the $2.1 million spent to bolster Gascón’s candidacy was offered up by a pair of Northern California benefactors with a history of donating to progressive causes.

Though she has been a force at some recent debates, painting herself as an alternative to two candidates with law enforcement backgrounds, records show public defender Rachel Rossi has generated little in the way of financial support.

Political observers say the sheer amount of money flowing into the race is unusual for a law enforcement election, and the heavy-handed contributions illuminate the high stakes: The winner will lead the largest prosecutor’s office in the nation with an outsize ability to influence policy agendas across California and the United States.

Though Lacey has championed a diversion program for defendants with mental illnesses, she is still seen as a typical “tough on crime” prosecutor compared with Gascón and Rossi, who both espouse platforms focused on restorative justice and maintaining public safety while lowering the prison population.

“You got the progressive against the more traditional — I don’t want to say conservative, but that’s really what it is, conservative — pro-law enforcement Jackie Lacey,” said Dermot Givens, a Los Angeles attorney and political consultant. “Society has moved past that, and now we’ll see if Los Angeles has moved past that.”

Lacey, whose reelection committee was formed in 2018, leads the way in direct fundraising, having collected $810,000, records show. Gascón has tallied $341,000, though he entered the race only in late October. Rossi has received $67,000 in direct donations, but failed to attract any money from outside committees.

Donors can contribute an unlimited amount of money to outside committees, which cannot coordinate with a candidate’s campaign.

That has played well for Gascón. The outside committee Run, George, Run received $1 million last month from Patty Quillin, the wife of Netflix Chief Executive Reed Hastings.

Quillin has donated to progressive candidates in Alameda County in the past, records show. Her husband had previously dumped more than $2 million into efforts such as Proposition 47 — the measure co-written by Gascón that turned low-level drug use and other offenses from felonies to misdemeanors — as well as efforts to repeal the death penalty in California, according to filings with the secretary of state.

Attempts to contact both Hastings and Quillin were unsuccessful.

Outside groups supporting Gascón also took in a combined $585,000 from Elizabeth Simons, who has donated tens of thousands to anti-death-penalty efforts and other criminal justice reform measures in recent years, records show. An email to Simons’ Bay Area-based clean energy foundation was not returned.

The outside group Gomez is volunteering for, Imagine Justice, has also said it will spend $1 million to help turn out voters for Gascón in South L.A.

The truckload of money from outside L.A. County would seem to bolster critics of Gascón who have tried to brand him as a carpetbagger, even though he grew up in Southern California and rose to the rank of assistant chief in the Los Angeles Police Department. Max Szabo, Gascón’s campaign spokesman, said the heavy dose of money from Northern California only serves to solidify his record on criminal justice reform.

“Those who care about injustice are going to get involved where they can make the biggest difference, and the biggest difference can be made in Los Angeles because it’s the mass-incarceration capital of the world,” he said.

Groups boosting Lacey have almost entirely received funding from law enforcement unions. In addition to the $1 million poured in by the Los Angeles Police Protective League, the union representing L.A. County sheriff’s deputies contributed $800,000 to a pro-Lacey committee that consists mostly of law enforcement groups. The Peace Officers Research Assn. of California has also contributed $107,500 to pro-Lacey efforts, while the union representing L.A. County prosecutors funneled $50,000 into the race.

Critics of Lacey have been quick to link her broad support among law enforcement unions to her record of rarely prosecuting use-of-force cases. Robert Harris, a director on the board of the LAPPL, scoffed at that notion and argued that the blitz of support is aimed at stopping Gascón, who many in law enforcement believe represents a brand of criminal justice policy that endangers public safety.

“We knew we were going to have to ward off some of that influence from outside our area who were going to try and sell this fake image of Gascón. We know who he really is,” Harris said. “We don’t need a D.A. to have an extreme makeover. We really want to support Jackie Lacey because she has that proven record of addressing some of the issues public safety-wise that we know are important to the communities that we serve.”

The committee donations have also raised questions about potential conflicts of interest in connection with one of the highest-profile individuals facing charges in Los Angeles: Harvey Weinstein.

Jury deliberations are ongoing in Weinstein’s New York trial on rape allegations. In Los Angeles, Lacey filed multiple counts of sexual assault against Weinstein last month.

Records show that Blair Berk, Weinstein’s lead defense counsel in Los Angeles, donated $1,000 to Lacey’s campaign in 2018. Gascón’s campaign has attacked Lacey over the contribution in the past. Berk declined to comment, and Lacey’s campaign said the appearance of a conflict was overblown.

“Virtually every D.A., including both George Gascón and D.A. Lacey, takes campaign contributions from defense attorneys, because these contributions do not represent a conflict of interest,” said Mac Zilber, a consultant for Lacey’s campaign. “Blair Berk first gave to D.A. Lacey eight years ago, years before the Weinstein case.”

Gascón’s campaign received a donation from Holly Baird, a public relations professional who has acted as a spokeswoman for Weinstein since the beginning of his New York criminal trial. Szabo said the campaign would return her $250 donation “to avoid even the slightest appearance of a conflict.”

In an email, Baird said she was “offended” by the Gascón campaign’s decision to return her contribution and said her personal views do not always align with those of people she works for.

“It’s antithetical to the #MeToo movement for the Los Angeles Times or anyone to misconstrue or question my intentions of donating $250 to attend a fundraiser for someone who is committed to criminal and social justice reform,” Baird wrote.

Though the dollar figures being thrown around in the race may have surprised some observers, Harris said bills add up quickly when an election affects voters from Palmdale to the South Bay.

“L.A. County is huge,” he said. “There are a lot of voters we have to communicate within a short amount of time.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.