In Northern California logging country, residents brace for a fight over their ‘magical’ redwood-lined road

- Share via

FORT DICK, Calif. — Wonder Stump Road passes beneath a canopy of needled redwood boughs that scatter sunbeams and cast an otherworldy green hue.

A drive along the narrow one-lane road is quiet. Tranquil.

But these days, terse hand-painted signs poke out from driveways of homes tucked in the woods.

We like our trees right where they ARE

LEAVE OUR TREES ALONE!!

In this sparsely populated, economically depressed northwest corner of California, people don’t have the tourist attractions that urbanites brag about. There are no five-star restaurants, no world-famous museums or amusement parks, no nightlife scene.

What people do have to boast about are trees — California’s iconic coast redwoods, the tallest trees on Earth. Wonder Stump Road is lined on both sides by them.

In a region transformed by logging over the last century, residents have long worried that someone is going to come along and chop down the so-called tree tunnel of Wonder Stump Road. Those fears were heightened last year when county workers marked scores of trees with bright orange paint.

“It means a lot to us, and it should mean a lot to everybody,” said Bryan Stanley, who has lived on Wonder Stump for two decades. “The trees are the lungs of the world, and if we lose those, we’re all gone.”

People here aren’t exactly tree huggers. Del Norte County is blue-collar country, where people talk seriously about carving a separate State of Jefferson out of California’s rural, conservative northern counties, and where loggers and fishermen have long bristled at government regulations.

“My family, we’re staunch conservatives. We’re not anti-logging or anything, but these trees don’t need to go,” said Mac Eller, a correctional sergeant at nearby Pelican Bay State Prison who has lived on Wonder Stump for 13 years.

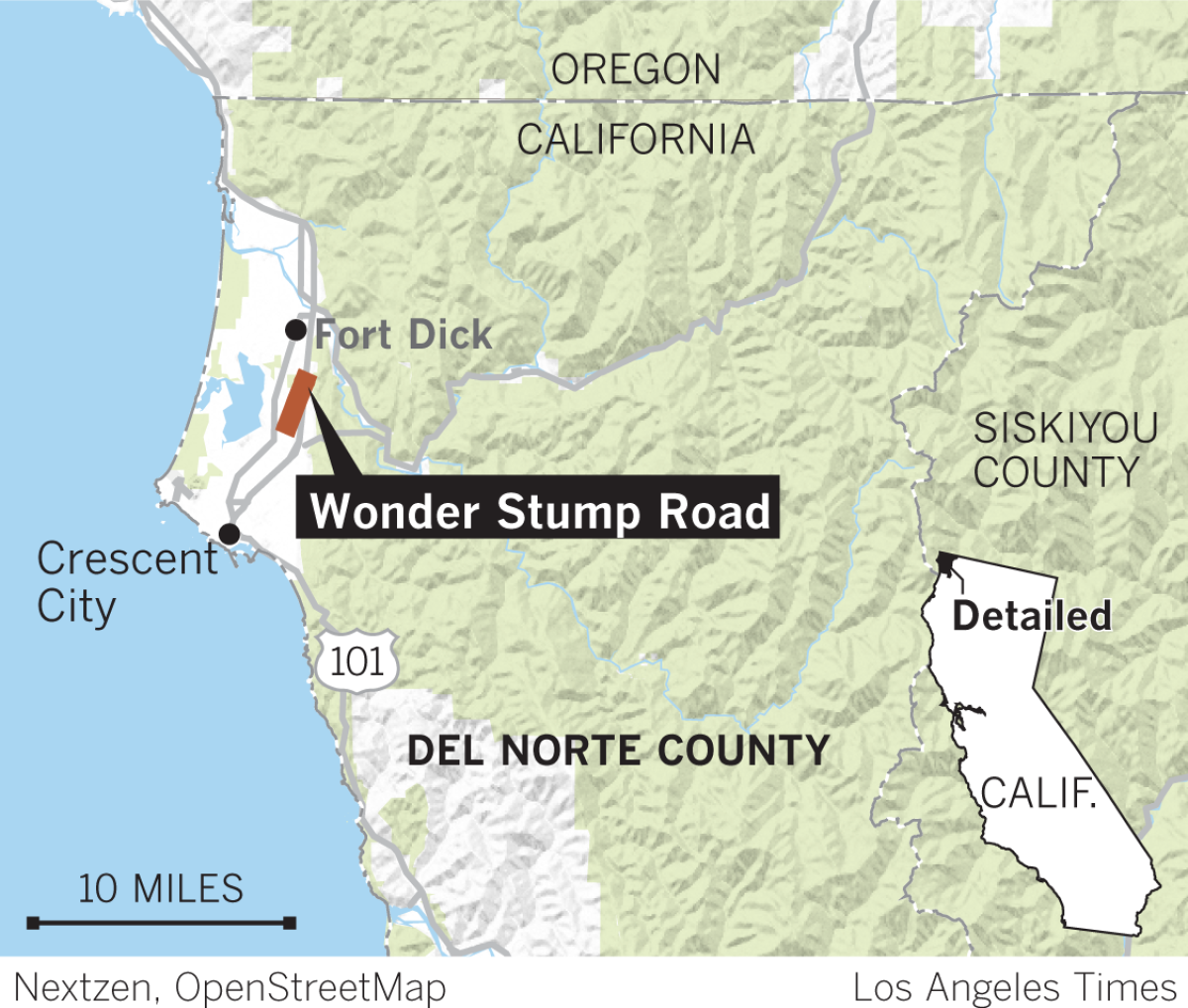

By the standards of a Los Angeles freeway, Wonder Stump Road — a 2.5-mile scenic byway between Crescent City and the tiny community of Fort Dick — is practically deserted. But in a mailer to residents this summer, Del Norte County officials called the road a “major collector” on which two-way traffic, including emergency vehicles and school buses, overwhelmed the one-lane road.

County officials said tree and root growth had made the road difficult to maintain and that crews would be assessing the road for potential changes. Whether the road will be widened or redwoods will be cut down is yet to be determined.

Residents say the county has been dismissive of their concerns. And one of the prevailing theories is that road crews complaining about how difficult it is to clean the road just don’t appreciate the value of old-fashioned hard work anymore.

“It just bugs me because it seems like they’re going to come out here one day and start working and nobody will have anything to say about it,” Stanley said.

Del Norte County Supervisor Gerry Hemmingsen said there had been “all kinds of rumors,” including that the county is going to sell the redwoods to the Japanese city of Rikuzentakata, which formed a sister city partnership with Crescent City after a 2011 earthquake and tsunami sent a barnacle-covered Japanese fishing boat across the Pacific Ocean that washed ashore in Crescent City two years later.

“I don’t know where all this information comes from,” Hemmingsen said. “It’s kind of comical at times. We don’t want to see the road deteriorate so bad that we can’t operate on it.”

Hemmingsen said the road had drainage problems and that fixes needed to be made “before it completely erodes the road away.” County road crews have a tough time using mechanized equipment on Wonder Stump and spend an inordinate amount of time cleaning it, he said.

Hemmingsen said it’s possible the county could add a culvert pipe and “widen the road a bit so you can’t drive down into the ditch and make it a little safer.”

“There has been no talk of cutting down all the trees. ... Evidently there’s a lot of mistrust in the government out there,” he said.

Virtually all coast redwoods grow in a narrow, fog-laden strip from Big Sur to southern Oregon. After the California Gold Rush, 95% of the original coast redwood forest was logged, according to Save the Redwoods League, a century-old conservation group.

Today, some 45% of the world’s protected old-growth redwood forests are in Del Norte and Humboldt counties within the boundaries of Redwood National and State Parks, a complex that includes Redwoods National Park, and Jedediah Smith, Del Norte Coast and Prairie Creek redwoods state parks, according to Save the Redwoods.

The redwoods of Wonder Stump Road grow just outside those boundaries, about a mile west of Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, and have fewer protections than those in the parks.

As second-growth trees — meaning they’re growing in a place that has been logged at least once — the Wonder Stump trees are practically babies compared with some 2,000-year-old coast redwoods.

That doesn’t make them any less special to residents, who say the county has been evasive.

A summer letter from Del Norte County Community Development Director Heidi Kunstal — which began, “You may have heard” the county was gathering public input on “potential improvements” — was dated July 22 and said that road assessment had begun three weeks earlier. It was the first written communication to property owners about possible changes to the road.

Asked by The Times why trees were marked with orange paint last year, Kunstal said: “It doesn’t really matter. It really wasn’t anything. ... The markings on the trees, they have no relevancy to what may or may not happen.”

Kunstal told the Del Norte Triplicate last year that the county’s road superintendent had marked the trees as candidates for removal but that a project had not been prioritized or funded.

Before being converted to a road, Wonder Stump was part of a rail line built in the early 1900s by the Hobbs, Wall & Co. timber company. The street is named after remnants of a massive redwood felled by loggers that had grown atop an older 8-foot-wide tree that had fallen more than a thousand years earlier, according to the Del Norte County Historical Society.

A Change.org petition asking for the trees along Wonder Stump to be left alone has more than 5,300 signatures.

“They know people get their panties in a bunch when we talk about this stuff,” Eller said.

Eller said his father, Clyde Eller, a former county supervisor, helped preserve the trees years ago by pushing the county to purchase its right of way because a timber company planned to cut the trees down.

“My dad used to be a logger. ... He had no problem cutting a tree down. His family used to hunt to live. They were poor and did whatever they had to do to survive,” Eller said. “And now, well, this road. He’s always liked the road, and it was unique and something our county had that was special.”

Eller’s wife, Donna, cares for her 96-year-old mother, who has Alzheimer’s and rarely leaves home. She cherishes the chance to wave at drivers pulling over to let her pass on the narrow road.

“We just wave at each other and smile and go on,” she said. “Sometimes, it could be days that I don’t get out of the house, and that interaction with someone is the only interaction I have. ... I always think, they’re driving south, where are they going to end up?”

Her property includes a fairy ring, a group of redwoods growing in a tight circle around the stump of a logged tree. Her grandkids picnic there.

Jeannie Reitterer, a retired Del Norte County school bus driver who lives on Wonder Stump, said she was frustrated the county was “using the school buses as an excuse” because she spent years driving a bus on the road four times a day and never had problems.

Reitterer said she also didn’t buy that emergency vehicles couldn’t get through. She’s had to call an ambulance three times — including once when her son fell out of a redwood tree and a branch pierced his back (he recovered just fine, she said) — and they got there within minutes, she said.

This summer, Reitterer said, a county worker was near her property with a surveyor’s tripod, and she asked him what he was doing. He told her they were just looking, but she remains suspicious.

“They’re being very vague,” she said. “It’s small-town politics and really hush-hush ... and that’s the scariest part about it. If they would just be honest and tell us what their intentions were, it would be more understandable. But they’re not.”

Susan McKay, who grew up on Wonder Stump, said she didn’t believe county officials truly appreciated “how unique and beautiful it is.”

“It has a magical feel to it,” she said. “Once it’s gone, it’s gone.”

In an undated black-and-white photograph, her grandfather, William McKay, is a young man clutching a rifle, perched atop — and dwarfed by — the original Wonder Stump. He was a logger, as was his father and his son, Susan McKay said. The image was made into a postcard decades ago, when the stump was a tourist attraction, she said.

Wonder Stump Road, she said, is a place of peace that needs to remain. It inspires poetry in her, including this haiku:

Notice while driving

Down the canopy of trees

The peace in your heart.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.