California enters uncharted territory: Massive blackouts, historically dangerous winds

- Share via

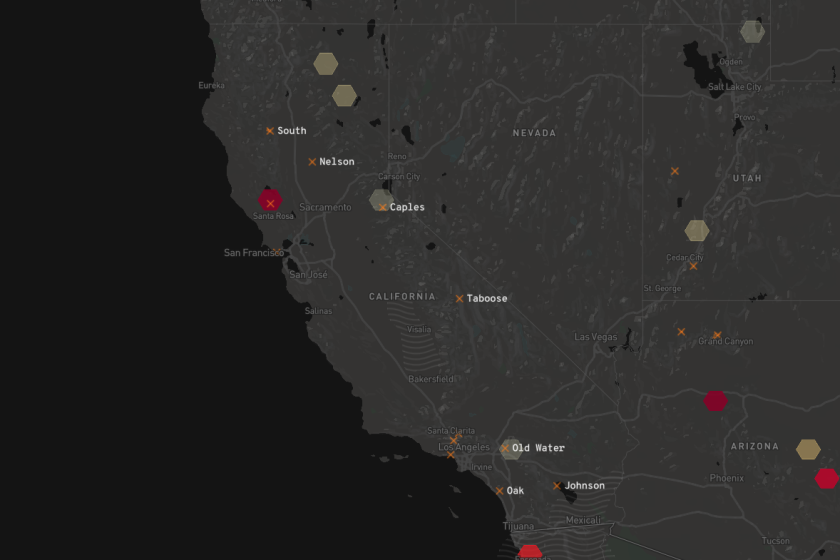

SAN FRANCISCO — Northern California braced for a weekend in uncharted territory as Pacific Gas & Electric Co. prepared to shut off power to more than 2 million people amid forecasts for one of the worst periods of fire weather in a generation.

It’s a perilous combination that left many anxiously planning for blackouts and the potential for more destructive wildfires, fueled by 36 hours of intense winds. Some fear they will have to confront fires without power, an experience those who fled this week’s Sonoma County fire described as terrifying.

The Diablo winds are expected to pick up Saturday evening and last until Monday morning, longer than the windstorms that fueled the three most catastrophic fires in California history.

“This is definitely an event that we’re calling historic and extreme,” said David King, meteorologist for the National Weather Service’s Monterey office, which manages forecasts for the Bay Area. “What’s making this event really substantial and historic is the amount of time that these winds are going to remain.”

PG&E warned the power outages could be spread across 36 counties from Humboldt to Santa Cruz to Bakersfield.

Residents are scrambling to prepare. Dr. Jeff Klingman, whose daughter is getting married in the Berkeley hills Saturday, plans to haul a generator to the wedding venue in case the power goes out.

Millions of Californians can do little more than watch as the lights go off, then on and maybe back off again during the blustery autumn of 2019.

The generator won’t light up the room but could provide power for the DJ.

“We don’t quite know what is going to happen,” he said. “Everyone is keeping their fingers crossed.”

Some forecasts said the East Bay‘s power would go out at 5 p.m. Saturday, just when the wedding is supposed to start.

Klingman said the venue does not allow real candles, so he plans to bring flashlights and possibly battery-operated candles.

“The uncertainty is crazy,” he said. “You just don’t know.”

Klingman purchased the generator on Amazon for $750 — not for the wedding, but for his job.

As chair of neurology for Kaiser Permanente, Klingman is in charge of evaluating emergency stroke patients at 21 Northern California hospitals. He uses a computerized system that provides high-quality video and sound. The generator was purchased to keep his computers at home running when he is on call to evaluate stroke patients, but on Friday he decided he would toss the machine into his van and take it to his daughter’s wedding.

“You don’t expect power to go out,” Klingman said. “But welcome to the Third World country that is America.”

The blackouts have become a political issue, with politicians attacking the bankrupt utility. The first shutdowns were chaotic, with PG&E officials saying they would improve communications this time around.

Gov. Gavin Newsom condemned PG&E for greed and mismanagement that led to this point in California history, with fires burning across the state and hundreds of thousands left in the dark.

“They simply did not do their jobs,” he said. “It took us decades to get here, but we will get out of this mess. We will do everything in our power to restructure PG&E so they are a completely different entity when they get out of bankruptcy. Mark my words. It is a new day of accountability.”

On Wednesday, PG&E shut down distribution lines that carry power directly to neighborhoods, homes and businesses in the Geyserville area before the wildfire began, but it kept electricity flowing through larger transmission lines the company said were built to withstand stronger winds. But the utility reported an outage at its 230-kilovolt transmission line at 9:20 p.m. in the area where the Kincade fire began, and officials are now investigating whether an equipment failure sparked the ignition.

Power outages leave those with disabilities especially vulnerable. Help remains a work in a progress

When PG&E and SoCal Edison shut off power, what happens to people with disabilities? As fires raged throughout California, residents simultaneously prepared for more shut-offs.

A PG&E worker who responded to the scene at 7:30 the next morning noticed that the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection had taped off the area around the base of the transmission tower. Cal Fire pointed out “what appeared to be a broken jumper on the same tower,” according to a mandatory report PG&E filed with the public utility commission.

The broken jumper cable could have sent a powerful discharge of current through the tower to the ground, said Michael Wara, director of the Climate and Energy Policy Program at Stanford University.

“It’s like a lightning strike,” Wara said. “The millisecond that jumper broke, you would have had that happen.”

He said the possibility that PG&E transmission equipment caused the fire could lead to more widespread preventive power outages this fall.

Transmission lines were linked to the deadly Camp fire last year in Butte County and are under investigation as a potential cause of the Saddleridge fire this month in the northern San Fernando Valley.

“Assuming they did their job right, what that means is we do not have adequate means of inspecting these towers to ensure they are safe,” Wara said. “And that means we cannot trust them in high-wind events and that means they need to be shut off in high-wind events.”

The wind conditions predicted for this weekend are much like those before the devastating wine country fires of 2017, said Craig Smith, a former PG&E weather expert and now a fire scientist with the consulting firm Jupiter Intelligence. Those fires killed 22 people in Sonoma County and nine in Mendocino County.

The area of highest risk includes the Bay Area and points north, including the northern Sierra Nevada foothills and California’s North Coast region, said Daniel Swain, climate scientist with UCLA and the National Center for Atmospheric Research. It’s been particularly unusual that the North Coast, the wettest part of the state, is still so dry at this point in autumn.

“This is the kind of event that makes me personally nervous, as somebody who has friends and family living in the fire zones in the Bay Area, and I don’t say that about all the events,” Swain said. “Hopefully, we get lucky and there are no major ignitions. But if they happen, it’s going to be really hairy Saturday night and Sunday. It’s looking really, really extreme.”

Sonoma wildfire stokes fears of more widespread power outages

PG&E has called some of this fall’s past winds extreme when that wasn’t necessarily the case, Swain said, but “this one really is meteorologically extreme.”

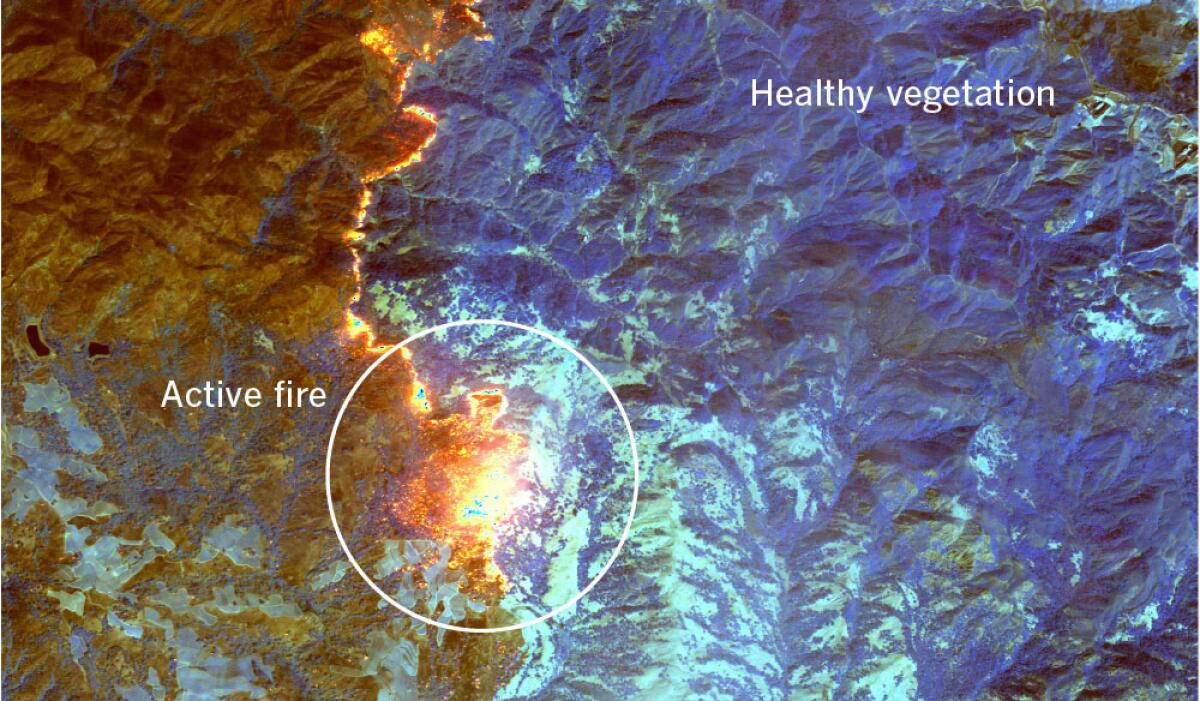

By Friday afternoon, the Kincade fire had destroyed 21 homes and scorched 21,900 acres. With a temporary lull in the wind, firefighters had still managed to reach only 5% containment.

“We’ll most likely see the fire spreading once again” Saturday evening, when gusts are expected to reach up to 75 mph, said Drew Peterson, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service. “I wouldn’t be surprised if we saw gusts between 80 and 85 mph.”

Then on Sunday, he said, conditions will worsen. The winds are expected to head downslope, reaching urban areas as far as Oakland, San Francisco and Sacramento.

Residents in Sonoma County got a preview this week when PG&E cut off power as the Kincade fire moved in.

Officials have issued a poor air quality alert, warning Bay Area residents to stay indoors Friday.

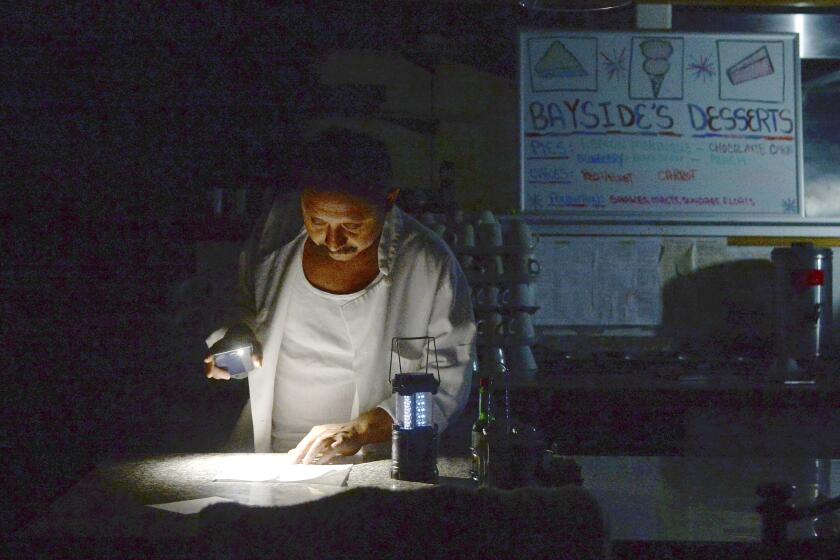

In Geyserville on Friday, as the fire burned in the surrounding hills, the power remained off in town and gas-powered generators raised a din.

Dino Bugica, 42, started his generator at his restaurant, Diavola, to keep his refrigerators going Thursday when the power was shut off. His house has no power, so he’s been spending the last two nights in the dark.

The upcoming weekend was supposed to be a busy one, with a celebration of fall and a Day of the Dead event. But with a violent windstorm forecast for Saturday night and the power likely to be off for days, it’ll be a veritable ghost town.

“What are you going to do?” he said. He sent his family to Healdsburg and has spent his evenings making food for firefighters.

When PG&E shut down power to Geyserville earlier this month, Bugica threw a pizza party by candlelight, which was a big hit. But he’s hoping that doesn’t become a tradition.

A few miles to the east, Pat Wright was getting ready to spend the next week without power, just in case.

Wright, 66, a retired heavy equipment operator, lives at the base of the hills that were in flames Thursday. He spent that night in his pickup truck, parked in the middle of the vineyard behind his house.

With no power, Wright can’t pump water from the well on his property. So before the winds arrived, he filled jugs and buckets and stocked up on bottled water.

But he has only enough gasoline to power his generator for three or four days. And if he leaves to pick up more fuel — assuming he can find a working pump — police probably won’t let him back inside the evacuation zone.

“Right now, they’ve got me kind of screwed,” he said.

Wright has gone through it before though. He said outages were commonplace before newer, stronger power lines were installed in the 1980s.

“This time of the year, the power would go out because the birds would come in, the starlings, at harvest time to eat the grapes,” he said. The sheer number of birds on the lines “would break them.... We were always out of power.”

He just thought those times were behind him.

In Shingletown, in the hills east of Redding, Shelly White was furious at the utility. Her adult daughter has cerebral palsy, is blind, diabetic and quadriplegic, and requires round-the-clock medical care, including oxygen and suction during seizures.

“We’re running around trying frantically to prepare,” she said. They need gas for a balky generator and backup battery. When the utility shut off power Oct. 9, they lost two freezers of meat.

But her biggest fear: The cellphone towers will no longer work. “We can’t even call 911,” she said.

“There has to be another solution.”

Willon reported from Sonoma County, Mozingo from Los Angeles, Lin from San Francisco and Dolan from Orinda, Calif. Times staff writers Hannah Fry, Alex Wigglesworth, Lelia Miller, Taryn Luna, James Rainey and Joseph Serna contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.